Mental representation

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 14:23, 28 April 2013 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

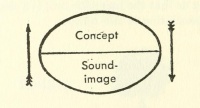

| + | [[Image:Sign and signifier as imagined by de Saussure.jpg|thumb|left|200px|[[Signified]] ([[concept]]) and [[signifier]] ([[sound-image]]) as imagined by [[Ferdinand de Saussure|de Saussure]]]] | ||

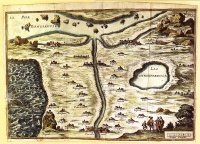

| + | [[Image:Carte du tendre.jpg|thumb|right|200px| | ||

| + | [[The map is not the territory]] is a concept. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Illustration: The ''[[Map of Tendre]]'' (''Carte du Tendre'')]] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | :''[[dream recollection]]'' | + | A '''mental representation''' (or '''cognitive representation'''), in [[philosophy of mind]], [[cognitive psychology]], [[neuroscience]], and [[cognitive science]], is a hypothetical internal cognitive [[symbol]] that represents external reality, or else a [[mental process]] that makes use of such a symbol: "a formal system for making explicit certain entities or types of information, together with a specification of how the system does this." |

| - | '''Representation''' is a term used in [[cognitive psychology]], [[neuroscience]], and [[cognitive science]] to refer to a hypothetical internal cognitive [[symbol]] that represents external reality. [[David Marr (psychologist)|David Marr]] defines representation as "a formal system for making explicit certain entities or types of information, together with a specification of how the system does this." [[Representationalism]] (also known as [[indirect realism]]) is the view that representations are the main way we access external reality. | + | Mental representation is the mental imagery of things that are both currently and not-currently seen or sensed by the sense organs. In [[contemporary philosophy]], specifically in fields of [[metaphysics]] such as [[philosophy of mind]] and [[ontology]], a mental representation is one of the prevailing ways of [[explanation|explaining]] and [[description|describing]] the nature of [[idea]]s and [[concept]]s. |

| - | '''Abstract''' | + | Mental representations (or mental imagery) enable representing things that have never been experienced as well as things that do not exist. Think of yourself traveling to a place you have never visited before, or having a third arm. These things have either never happened or are impossible and do not exist, yet our brain and mental imagery allows us to imagine them. Although visual imagery is more likely to be recalled, mental imagery may involve representations in any of the sensory modalities, such as hearing, smell, or taste. [[Stephen Kosslyn]] proposes that images are used to help solve certain types of problems. We are able to visualize the objects in question and mentally represent the images to solve it. |

| - | An analysis is given of the status of the concept of representation in psychology, and the various ways it is used, including its explanatory status and its use as a causal agent. | + | Mental representations also allow you to experience things right in front of you—though the process of how the brain interprets the [[Mental content|representational content]] is debated. |

| - | '''1. The concept of representation''' | + | ==Representational Theories of Mind== |

| - | ''1.1. Representation: representing and representations'' | + | [[Representationalism]] (also known as [[Direct and indirect realism|indirect realism]]) is the view that representations are the main way we access external reality. Another major prevailing [[philosophical theory]] posits that concepts are entirely [[abstract object]]s. |

| - | This paper concerns the status of the concept of representation and the psychological use of this concept as an explanatory construct. As we have seen in the Introduction of this issue, representation - in its most general sense - seems to mean "something" that substitutes something else. However, it is enough to look up any dictionary definition of representation to realize that the term is not always used to refer to "something" but also to some activity or operation. A rather basic distinction to make, indeed, is that representation may be either the act of representing or the product of representing. This distinction is not only relevant from a lexical point of view, but also turns out to be a psychologically important distinction, that is the distinction between process and content. | + | The representational theory of mind attempts to [[explanation|explain]] the nature of [[idea]]s, [[concept]]s and other [[mental content]] in [[contemporary philosophy|contemporary]] [[philosophy of mind]], [[cognitive science]] and [[experimental psychology]]. In contrast to theories of naive or [[direct realism]], the representational theory of mind postulates the actual existence of mental representations which act as intermediaries between the [[observation|observing]] subject and the [[object (philosophy)|objects]], processes or other entities observed in the external world. These intermediaries stand for or represent to the mind the objects of that world. |

| - | Process and content were first distinguished as far back as Brentano. Typically, when talking about content one can use the plural form ("representations"), but not when talking about process, which we may call "representing". We can find corresponding distinctions also in other psychological processes: thinking and thoughts; perceiving and percepts; storing and memories, etc. Here, in order to stress this difference, I propose to adopt a simple terminology: in the functional sense of the process of representation I shall use the term "representing" and in the structural sense of content of representation I shall use the term "representations"; I shall continue using the word "representation" in the most general (or ambiguous) sense, which includes both. This terminology perhaps is not particularly new, but I find it very useful. | + | For example, when someone arrives at the belief that his or her floor needs sweeping, the representational theory of mind states that he or she forms a mental representation that represents the floor and its state of cleanliness. |

| - | I am stressing this difference because the psychological significance is different in the two cases. If attention is directed towards representations as products, then the main focus concerns their form, their structure. On the other hand, in the "representing" sense, attention is shifted to dynamic and time-related aspects, which seem more natural (in my opinion, the time dimension continues to be neglected in psychology). Furthermore, representing seems more appealing from the neural point of view. But I shall return later to the subject of why representing may be more appealing than having representations. | + | The original or "classical" representational theory probably can be traced back to [[Thomas Hobbes]] and was a dominant theme in classical [[empiricism]] in general. According to this version of the theory, the mental representations were images (often called "ideas") of the objects or states of affairs represented. For modern adherents, such as [[Jerry Fodor]], [[Steven Pinker]] and many others, the representational system consists rather of an internal [[Language of thought hypothesis|language of thought]] (i.e., mentalese). The contents of thoughts are represented in symbolic structures (the formulas of Mentalese) which, analogously to natural languages but on a much more abstract level, possess a [[syntax]] and [[semantics]] very much like those of natural languages. For Augusto (2014), at this abstract, formal level, the syntax of thought is the set of symbol rules (i.e., operations, processes, etc. on and with symbol structures) and the semantics of thought is the set of symbol structures (concepts and propositions). Content (i.e., thought) emerges from the meaningful co-occurrence of both sets of symbols that, in turn, is determined by the semantic protoness of syntax and the syntactic protoness of semantics. For instance, "8 x 9" is a meaningful co-occurrence, whereas "CAT x §" is not; "x" is a symbol rule called for by symbol structures such as "8" and "9", but not by "CAT" and "§". |

| - | ''1.2. Representation as "internal entities or events"'' | + | === Strong vs Weak, Restricted vs Unrestricted === |

| + | There are two types of representationalism, strong and weak. Strong representationalism attempts to reduce phenomenal character to intentional content. On the other hand, weak representationalism claims only that phenomenal character supervenes on intentional content. Strong representationalism aims to provide a theory about the nature of phenomenal character, and offers a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. In contrast to this, weak representationalism does not aim to provide a theory of consciousness, nor does it offer a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. | ||

| - | Now I want to continue examining other aspects of the basic meaning of the term representation. We started with the basic definition as "standing for something else". The psychological use of the concept of representation, however, seems more general than this, and indeed it might not be limited to substituting. | + | Strong representationalism can be further broken down into restricted and unrestricted versions. The restricted version deals only with certain kinds of phenomenal states e.g. visual perception. Most representationalists endorse an unrestricted version of representationalism. According to the unrestricted version, for any state with phenomenal character that state’s phenomenal character reduces to its intentional content. Only this unrestricted version of representationalism is able to provide a general theory about the nature of phenomenal character, as well as offer a potential solution to the hard problem of consciousness. The successful reduction of the phenomenal character of a state to its intentional content would provide a solution to the hard problem of consciousness once a physicalist account of intentionality is worked out. |

| - | More generally, in the psychological sense representations are entities we postulate as internal to the organism. Thus representations can be conceived as internal entities or events. If we speak of substitution or of substitutes, we are actually speaking of one possible function of these entities or processes; but it is questionable whether this function of substitution is the only one or the most relevant. But this point concerning the function of representation deserves discussion in itself, something that we shall do later. | + | === Problems for the Unrestricted Version === |

| + | When arguing against the unrestricted version of representationalism people will often bring up phenomenal mental states that appear to lack intentional content. The unrestricted version seeks to account for all phenomenal states. Thus, for it to be true, all states with phenomenal character must have intentional content to which that character is reduced. Phenomenal states without intentional content therefore serve as a counterexample to the unrestricted version. If the state has no intentional content its phenomenal character will not be reducible to that state’s intentional content, for it has none to begin with. | ||

| - | '''2. Reasons for postulating representations''' | + | A common example of this kind of state are moods. Moods are states with phenomenal character that are generally thought to not be directed at anything in particular. Moods are thought to lack directedness, unlike emotions, which are typically thought to be directed at particular things e.g. you are mad ''at'' your sibling, you are afraid ''of'' a dangerous animal. People conclude that because moods are undirected they are also nonintentional i.e. they lack intentionality or aboutness. Because they are not directed at anything they are not about anything. Because they lack intentionality they will lack any intentional content. Lacking intentional content their phenomenal character will not be reducible to intentional content, refuting the representational doctrine. |

| - | ''2.1. Everyday psychology: phenomenological evidence - intentional explanation'' | + | Though emotions are typically considered as having directedness and intentionality this idea has also been called into question. One might point to emotions a person all of a sudden experiences that do not appear to be directed at or about anything in particular. Emotions elicited by listening to music are another potential example of undirected, nonintentional emotions. Emotions aroused in this way do not seem to necessarily be about anything, including the music that arouses them. |

| - | Before, we should first examine a more basic question: why internal entities or events are postulated? I shall mention some reasons, first in everyday or commonsense psychology and then in scientific psychology. In everyday psychology, an early boost for postulating representation, or rather internal representations, comes from subjective experiences. There are naive or folk reasons: I feel the evidence of psychological states inside me (thinking, emotions, images...) and therefore I suppose that something in the head of other persons must explain their behaviour and also their psychological states, that they report to have. So there is a phenomenological evidence of meaning, or the evidence that mental activities persist over time (the phenomenon of memory). It has to be remarked that, in everyday psychology, representations are almost always preferred to representing: it seems easier to consider ready-made thoughts rather than processes of thinking. Here, then, representation is certainly a useful concept in that it constitutes the basis for the intentional system of explanation, typical of commonsense psychology (desires, beliefs, etc. represent internal states; images do represent objects, etc.). | + | === Responses === |

| + | In response to this objection a proponent of representationalism might reject the undirected nonintentionality of moods, and attempt to identify some intentional content they might plausibly be thought to possess. The proponent of representationalism might also reject the narrow conception of intentionality as being directed at a particular thing, arguing instead for a broader kind of intentionality. | ||

| - | ''2.2. Scientific psychology: mediating between stimulus and response'' | + | There are three alternative kinds of directedness/intentionality one might posit for moods. |

| + | * Outward Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have a certain kind of outwardly focused representational content. | ||

| + | * Inward Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have a certain kind of inwardly focused representational content. | ||

| + | * Hybrid Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have both a certain kind of outwardly focused representational content and a certain kind of inwardly focused representational content. | ||

| + | In the case of outward directedness moods might be directed at either the world as a whole, a changing series of objects in the world, or unbound emotion properties projected by people onto things in the world. In the case of inward directedness moods are directed at the overall state of a person’s body. In the case of hybrid directedness moods are directed at some combination of inward and outward things. | ||

| - | A second reason for postulating representation is more technical and belongs to psychologists. The early, naive "something in the head" in scientific psychology becomes less vague, but unfortunately also more confusing, because in psychological literature the term is referred to different phenomena, and at different levels. A list of examples of representations (or of sets of representations) could be endless: I shall mention only some of them: linguistic symbols, mathematical symbols, visual patterns, even visual fields or images. Also high-level concepts (sometimes similar to those of everyday psychology) are considered as working as representations, both in natural and artificial systems: so we have categories, beliefs, propositional attitudes, schemata, semantic networks, and so on. Recently representation is also spoken of in connectionist models, and some even speak of "neural" representation. We have to admit that the confusion is overwhelming. | + | === Further Objections === |

| + | Even if one can identify some possible intentional content for moods we might still question whether that content is able to sufficiently capture the phenomenal character of the mood states they are a part of. Amy Kind contends that in the case of all the previously mentioned kinds of directedness (outward, inward, and hybrid) the intentional content supplied to the mood state is not capable of sufficiently capturing the phenomenal aspects of the mood states. In the case of inward directedness, the phenomenology of the mood does not seem tied to the state of one’s body, and even if one’s mood is reflected by the overall state of one’s body that person will not necessarily be aware of it, demonstrating the insufficiency of the intentional content to adequately capture the phenomenal aspects of the mood. In the case of outward directedness, the phenomenology of the mood and its intentional content do not seem to share the corresponding relation they should given that the phenomenal character is supposed to reduce to the intentional content. Hybrid directedness, if it can even get off the ground, faces the same objection. | ||

| - | The best thing to do would be to evaluate the explanatory role of mental representation not "in the vacuum" but in some particular theoretical framework. [The philosopher Cummins has suggested a similar point of view]. But this is practically impossible here, because virtually all theories in the history of psychology have had to come to grips with representation and could be mentioned. | + | == Philosophers == |

| + | There is a wide debate on what kinds of representations exist. There are several philosophers who bring about different aspects of the debate. Such philosophers include Alex Morgan, Gualtiero Piccinini, and Uriah Kriegel—though this is not an exhaustive list. | ||

| - | Anyway, a good starting point for discussion seems to be the observation that representations are introduced in scientific psychology essentially as mediating entities. In order to explain behaviour and mental states, psychology needs entities or processes which mediate between stimuli and responses, or between inputs and outputs or, more widely, between situations and behaviour (at least, if humans are to be understood as systems which are not completely determined by their environment). This idea of an internal mediation between the environment and the organism's action is typical of modern psychological conceptions, but is not necessarily the only one possible. For example, the most classical philosophical positions have considered representation rather like a sort of internal reality which we find naturally inside us (no matter if there was the problem of comparing it to the so-called "true" reality... Hence the well-known classical dualism, and hence many philosophical discussions concerning the adequacy of internal reality with respect to the so-called "true" reality, the problem of misrepresentation, and similar arguments that amuse philosophers so much). | + | === Alex Morgan === |

| - | As is well known, the idea of "mediating entities" historically came in psychology from the need to overcome the typical impasse of the behaviorist position concerning the "gap" between stimuli and responses. In substance, cognitivists said: the gap between stimuli and responses can be filled if we consider that stimuli do not act as such, but are manipulated, processed. Hence the need for representations. | + | There are "job description" representations. That is representations that (1) represent something—have [[intentionality]], (2) have a special relation—the represented object does not need to exist, and (3) content plays a causal role in what gets represented: e.g. saying "hello" to a friend,giving a glare to an enemy. |

| - | We have up to now considered representation as an internal event (a process, or a product of a process) which can explain psychological phenomena by virtue of its working as a causal connection between stimuli and responses. Now I want to ask two questions, which are related to each other. | + | Structural representations are also important. These types of representations are basically mental maps that we have in our minds that correspond exactly to those objects in the world (the intentional content). According to Morgan, structural representations are not the same as mental representations—there is nothing mental about them: plants can have structural representations. |

| - | where does the causal power of representations come from? | + | There are also internal representations. These types of representations include those that involve future decisions, episodic memories, or any type of projection into the future. |

| - | what function (or functions) is (are) attributed to representations by psychological theories? | + | |

| - | We shall examine these two issues in the next two sections. | + | |

| - | '''3. Causal power of representations''' | + | === [[Gualtiero Piccinini]] === |

| - | We have seen that, in general, representations are given an explanatory power inasmuch as they act as causes. The paradigm is the same as that in physics, with the difference that here one speaks of internal rather than external causes. It is interesting, therefore, to know where the causal power of representations comes from. | + | In Piccinini's forthcoming work, he discusses topics on natural and [[nonnatural]] mental representations. He relies on the natural definition of mental representations given by Grice (1957) where ''P entails that P''. e.g. Those spots mean measles, entails that the patient has measles. Then there are nonnatural representations: ''P does not entail P''. e.g. The 3 rings on the bell of a bus mean the bus is full—the rings on the bell are independent of the fullness of the bus—we could have assigned something else (just as arbitrary) to signify that the bus is full. |

| - | ''3.1. Symbolic representation'' | + | === Uriah Kriegel === |

| - | 3.1.1. Personality & Social Psychology: representation as "subjective" reality | + | There are also objective and subjective mental representations. Objective representations are closest to tracking theories—where the brain simply tracks what is in the environment. If there is a blue bird outside my window, the objective representation is that of the blue bird. Subjective representations can vary person-to-person. For example, if I am colorblind, that blue bird outside my window will not ''appear'' blue to me since I cannot represent the blueness of blue (i.e. I cannot see the color blue). The relationship between these two types of representation can vary. |

| - | In some areas of psychology (especially in personality theories or in social psychology) the concept of "representation" is often used (to tell the truth, not so differently from everyday psychology) to express the assumption that individuals do not act on the basis of "objective" patterns of the world, but on the basis of their so-called "internal representations" of it, which do not necessarily correspond to what actually happens in the world, but can be abstractions, simplifications, perhaps misrepresentations or even illusions. Even if this does not necessarily involve the earlier-mentioned risk of a dualism between reality as it is and as it appears, representation as a "subjective" reality here is strongly opposed to the "objective" reality, (which - by the way - usually happens to be the one of psychologists). Moreover, representations in this sense are, in general, complex ones (e.g. categories, expectations, interpretations, scripts), and they can explain fears, problems, behaviour - only if they are properly interpreted and connected with the right meaning. Here the risk is of being too general, vaguely confusing representation with having any idea, knowledge, or thinking. It was to avoid these very risks that scientific psychology abandoned the naive way of explaining. | + | (a) Objective varies, but the subjective does not: e.g. brain-in-a-vat |

| - | 3.1. 2. Cognitive psychology: representations as symbols to be interpreted | + | (b) Subjective varies, but the objective does not: e.g. color-inverted world |

| - | Cognitive psychology perhaps is better placed because it restricts itself to the elements that make thinking possible. We know that in cognitive science it has become commonplace to see cognitive activities as information processing. Cognitivism considers knowledge acquisition and management in terms of symbol manipulation which follows formal rules. Representation in this perspective is the postulation of a set of internal entities standing for other things, separate from these other things which they represent. | + | (c) All representations found in objective and none in the subjective: e.g. thermometer |

| - | But, if this is true, in this aspect representation from the standpoint of cognitive science is not different from other psychological theories, because the causal power of representations still comes from their interpretation. Their simple existence is not enough to give representations a causal power. The causal power of representations doesn't come from their mere existence, but rather from their interpretation. In other words: because they are symbolic. The medium that conveys meaning may have an arbitrary form, and there are formal rules that make going from the sign to its interpretation possible. The model is language, and indeed this perspective is often called the one that resorts to a "language of thought". | + | (d) All representations found in subjective and none in the objective: e.g. an agent that experiences in a void. |

| - | ''3.2. Non-symbolic representation'' | + | Eliminativists think that subjective representations don't exist. Reductivists think subjective representations are reducible to objective. Non-reductivists think that subjective representations are real and distinct. |

| - | + | ||

| - | Psychoanalysis: simple existence | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In psychological history, of course, this has not been the only proposal, even if we have to admit that it has become the most fashionable. We can take - as an example of a different approach - psychoanalysis, which is interesting because it has been influential in general psychological culture. The peculiarity of Freud's system is that representations which are non-accessible but still have a causal power are allowed. Here representations are meaningful ideas, but different from those of commonsense. They are symbols, in a different sense than in cognitive theory, symbols as contents which replace other contents, and this replacement occurs because the original contents are not acceptable, hence not representable. In this sense, differently from the cognitive perspective, the causal power of representations comes from their mere existence. We shall see later other examples of so- called representations which act by mere existence, one example is the connectionist perspective. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The important thing now is that the question we asked earlier (where does the causal power of representations come from?) can be answered in two ways: according to some perspectives, it comes from the interpretation of internal entities; according to other perspectives, the causal power comes rather from their mere existence. We can call these two cases symbolic and non- symbolic representation. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In the next section we shall examine the second question previously asked, about the functions that psychological theories attribute to internal entities. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | '''4. Functions of representations''' | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ''4.1. The substitution function of internal entities: making actual (storing/anticipating)'' | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | We have said that, in the most common definition, representations are not just any kind of internal entities but are considered internal substitutes. But what does it mean to have internal substitutes? What are they meant to substitute? Clearly, substitution is necessary when something is not present but still required. Then, in principle, if representation is substitution, we don't need representation to manage present, actual events. Rather, we need representation to cope with past and future events. On the one hand we have to resort to representation when we need to store and retrieve information about something that has already happened. On the other hand we need representation when we need information to be used for something that has not yet happened, but which we ourselves can control, that we can make happen, that we can construct. In other words, our behaviour (of course in the widest sense, including language for example). We can find this sense of representation in famous psychologists like Bruner and Piaget. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Following an old but influential distinction put by Bruner et al. (1966), we can describe a not particularly common kind of representation, the one that he calls "active representation", which has a different function from the usual one, it has the function of anticipating doing or action. It is an internal organization of behaviour occurring before behaviour. A similar proposal, perhaps in clearer terms, can be found in Piaget's theory, where representation at the beginning reflects action and afterwards becomes more abstract (according to Piaget, as we know, the organization of thought is based on the earlier organization of action). In these senses, representation does not imply symbol manipulation, but there is a connection with action. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Then, if we are to postulate internal representation as "internal substitution", this can be understood as a function of "making actual" what is not actual. And, more precisely, this function includes two subfunctions: | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | 1) storing past perceptions or past behaviour; | + | |

| - | 2) anticipating perception or behaviour (antecedents of our behavior, which in some way help to "plan" its performance: e.g. motor schemata, pre-linguistic representations, attitudes etc.). | + | |

| - | Why should we need something internal that substitutes behaviour? It is the same reason why planning is necessary for any intelligent system. Actually trying any possible action would simply not be economic. Hence we need motor schemata for planning action at the lowest level, and also mental operations or "moves" when we have to solve a problem. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In what sense do these representations substitute action? They do in the sense that they have the function of making action possible only in the mind. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | It is interesting to note that the same functions also hold for artificial systems: in order to work properly, they have to store past events and also instructions on how to produce output states. But this is not true of all systems, because some of them (neural networks), as we know, don't need instructions. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ''4. 2. The correspondence function of mental entities'' | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Now I shall mention a different perspective in considering the function of internal entities, which gives up the idea of substitution. One can say: perhaps internal events, in fact, do not substitute anything, do not anticipate anything. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | According to this perspective, the main function of representation is the one I shall call correspondence. According to this idea, the effect of stimulation starts with transduction and hence gives rise to a modification of neural states. Something happens, in accordance with physical or physiological constraints. There is a variation of internal states corresponding to a variation of external (or bodily) states: in other words, a covariation. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | From the psychological point of view, a similar idea was put by Gestalt psychologists as the isomorphism postulate: this means that when having the same perceptions we always have the same internal processes, whatever they are. However, the usefulness of such a concept is dubious if we say whatever they are, and we are not able to identify what these processes are. Even if we could describe them accurately as neural processes, the same old problem of connecting these processes to precise psychological processes would still remain. This idea is relevant in neural networks. It may be claimed that networks do represent because they change their state in a non-random way, closely related to changes in the input. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In some connectionist systems it is claimed that symbolic representations are not required: in these systems, at least in multi- layered and subsymbolic ones, there is still a sort of internal storage, which is in the weights of connections, but there is not an understandable relationship either with the input (the past) or with the output (the future). By "not understandable" I mean that the function of these internal states, as they are not symbolic, cannot be understood by someone who inspects the network while it is working. Hence the well- known problem of deciding whether these internal states are still to be called representations or not. Why resort to non-symbolic representation? If it is synonimous with a generical internal event, it could be called "non-symbolic processing" | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | It's easy to see that the correspondence function of representation is perfectly compatible with the earlier-mentioned non-symbolic representation. This is what we "find" in our senses, not what we construct. We know that there is experimental support to the isomorphism hypothesis [for example, Huber & Weisel's findings]. Is this enough? Perhaps not, since we know from experimental psychology that there is wide support also for the symbolic representation hypothesis. We need both but we don't know how to consider them in a single theoretical framework. The real problem is that we don't know how symbolic representation arises from the non-symbolic one, or anyway how they are related. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | '''5. Representing as using representations or constructing representations''' | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | From what has been said up to now, it's easy to see that in psychology greater importance has been given to representations rather than to representing (linguistic symbols, beliefs, schemata, etc.: what else are they, if not ready-made representations?) This approach of giving more importance to representations has a respectable tradition; we know that especially the psycholinguistic approach is involved in this tradition. Sometimes internal representations have been called "tokens" or something similar, and this seems to reflect a topographic conception of cognition, which postulates ready-made pieces of meaningful material, of meaningful building blocks. This is the conception of representation as a language of thought, and this conception is also bound to the notorious "compositionality" requirement that some philosophers have pointed out. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Perhaps "representing" is avoided because it is difficult to consider a process in abstract terms, without specifying its content. And perhaps there is another reason. When one postulates a process it seems natural to imply an "agent" that carries out this process. Of course, this agent need not be a homunculus inside our skulls, but may take more sophisticated forms, like origins or causes, or forces (and so on) which drive the process. But the problem, in any case, is that in making our theories, as students of psychological processes, we can only use our logic tools: we cannot avoid considering processes or events as if they were predicates. Being predicates, they require arguments (what is the subject, what is the object) and these arguments are hard to specify when talking about mental processes. In my opinion, this is one of the reasons why understanding internal processes in non-subjective terms is so difficult. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | However, we cannot deny that, unlike the commonsense perspective, in scientific psychology also a process of representing is sometimes put into the field, once again in order to account for the gap between situation and behaviour. But this option of conceiving representation as a process of representing is rarer. The main perspectives that come to mind are: personal styles in social psychology (not what one believes but the way one believes) or, of course, the typical position of cognitivist psychology (for example, not particular schemata but the general way schemata are constructed or managed). Here we are dealing with the sort of cognitive machinery that has been called (Pylyshyn, 1984) the functional architecture, which makes representing possible. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | But here we must be careful, because in most cases the difference between representations and representing is only apparent, because representing often is merely a process of managing ready- made representations. In this case, it only means using two different ways to say, in fact, the same thing. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In speaking of representing, instead, I mean a radically different conception: I am referring to a process not of using representations but of constructing representations. The gist of the previous discussion is that when those internal entities called representations are used to substitute external events (to store information or to anticipate action), a symbolic interpretation is required. These representations seem to be constructed, sometimes with effort. On the contrary, when internal entities are used to reflect external events, there is no such need for a symbolic interpretation but their effect seems to be found, already ready. Hence the feeling of an automatic internal reality. In my opinion, most of the problems of the concept of representation come from the fact that, according to what we know up to now, these seem to be two concepts of representation, and there is no way to consider them in an overall framework. This is the difficulty of reconciling finding and constructing (passive/active, meaningless/meaningful, nonsymbolic/symbolic). | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | '''6. Conclusion: proposing a new metaphor''' | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In conclusion I would like just to outline (really in a flash) a working hypothesis about how the symbolic function of representing could arise not in managing representations but in "constructing" them. All evidence coming from neuropsychology tells us that this constructing should be conceived as a process in which there are first internal events which simply reflect stimuli (at a low-level, a neural level). What happens of these corresponding or isomorphic events? subsequently they should detach themselves from the simple correspondence function, they must stop working as simple mirrors and start to substitute. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Perhaps a new metaphor to be explored may be proposed, coming from biology. The process we are discussing of, might be similar to the process whereby cells copy themselves while reproducing, but with errors, or with sorts of "mutations", and from these errors information and organization arise. This idea has to be explored, and neural networks might be a good field to try it. I am working in this direction but perhaps I need help from biologists. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | A '''(mental) representation''', in [[philosophy of mind]], [[cognitive psychology]], [[neuroscience]], and [[cognitive science]], is a hypothetical internal cognitive [[symbol]] that represents external reality, or else a mental process that makes use of such a symbol. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In [[contemporary philosophy]], specifically in fields of [[metaphysics]] such as [[philosophy of mind]] and [[ontology]], a mental representation is one of the prevailing ways of [[explanation|explaining]] and [[description|describing]] the nature of [[idea]]s and [[concept]]s. | + | |

| + | The debates about mental representation do not end here. In fact, they lead to other discussions such as content of mental states, embodied cognition, consciousness, and phenomenology. | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| + | * [[Cognitive model#Dynamical systems|Representation in dynamical systems models of cognition]] | ||

| * [[Object of the mind]] | * [[Object of the mind]] | ||

| * [[Knowledge representation]] | * [[Knowledge representation]] | ||

| * [[Perception]] | * [[Perception]] | ||

| * [[Representative realism]] | * [[Representative realism]] | ||

| - | * [[Indirect realism]] | + | * [[Condensation (psychology)]] |

| - | * [[Knowledge representation]] | + | * [[Visual space]] |

| - | * [[Representationalism]] | + | * [[Mental model]] |

| - | * [[Perception]] | + | * [[Worldview]] |

| - | {{GFDL}} | + | * [[Paradigm]] |

| + | * [[Mindset]] | ||

| + | * [[Set (psychology)]] | ||

| + | * [[Schema (psychology)]] | ||

| + | * [[Basic beliefs]] | ||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

A mental representation (or cognitive representation), in philosophy of mind, cognitive psychology, neuroscience, and cognitive science, is a hypothetical internal cognitive symbol that represents external reality, or else a mental process that makes use of such a symbol: "a formal system for making explicit certain entities or types of information, together with a specification of how the system does this."

Mental representation is the mental imagery of things that are both currently and not-currently seen or sensed by the sense organs. In contemporary philosophy, specifically in fields of metaphysics such as philosophy of mind and ontology, a mental representation is one of the prevailing ways of explaining and describing the nature of ideas and concepts.

Mental representations (or mental imagery) enable representing things that have never been experienced as well as things that do not exist. Think of yourself traveling to a place you have never visited before, or having a third arm. These things have either never happened or are impossible and do not exist, yet our brain and mental imagery allows us to imagine them. Although visual imagery is more likely to be recalled, mental imagery may involve representations in any of the sensory modalities, such as hearing, smell, or taste. Stephen Kosslyn proposes that images are used to help solve certain types of problems. We are able to visualize the objects in question and mentally represent the images to solve it.

Mental representations also allow you to experience things right in front of you—though the process of how the brain interprets the representational content is debated.

Contents |

Representational Theories of Mind

Representationalism (also known as indirect realism) is the view that representations are the main way we access external reality. Another major prevailing philosophical theory posits that concepts are entirely abstract objects.

The representational theory of mind attempts to explain the nature of ideas, concepts and other mental content in contemporary philosophy of mind, cognitive science and experimental psychology. In contrast to theories of naive or direct realism, the representational theory of mind postulates the actual existence of mental representations which act as intermediaries between the observing subject and the objects, processes or other entities observed in the external world. These intermediaries stand for or represent to the mind the objects of that world.

For example, when someone arrives at the belief that his or her floor needs sweeping, the representational theory of mind states that he or she forms a mental representation that represents the floor and its state of cleanliness.

The original or "classical" representational theory probably can be traced back to Thomas Hobbes and was a dominant theme in classical empiricism in general. According to this version of the theory, the mental representations were images (often called "ideas") of the objects or states of affairs represented. For modern adherents, such as Jerry Fodor, Steven Pinker and many others, the representational system consists rather of an internal language of thought (i.e., mentalese). The contents of thoughts are represented in symbolic structures (the formulas of Mentalese) which, analogously to natural languages but on a much more abstract level, possess a syntax and semantics very much like those of natural languages. For Augusto (2014), at this abstract, formal level, the syntax of thought is the set of symbol rules (i.e., operations, processes, etc. on and with symbol structures) and the semantics of thought is the set of symbol structures (concepts and propositions). Content (i.e., thought) emerges from the meaningful co-occurrence of both sets of symbols that, in turn, is determined by the semantic protoness of syntax and the syntactic protoness of semantics. For instance, "8 x 9" is a meaningful co-occurrence, whereas "CAT x §" is not; "x" is a symbol rule called for by symbol structures such as "8" and "9", but not by "CAT" and "§".

Strong vs Weak, Restricted vs Unrestricted

There are two types of representationalism, strong and weak. Strong representationalism attempts to reduce phenomenal character to intentional content. On the other hand, weak representationalism claims only that phenomenal character supervenes on intentional content. Strong representationalism aims to provide a theory about the nature of phenomenal character, and offers a solution to the hard problem of consciousness. In contrast to this, weak representationalism does not aim to provide a theory of consciousness, nor does it offer a solution to the hard problem of consciousness.

Strong representationalism can be further broken down into restricted and unrestricted versions. The restricted version deals only with certain kinds of phenomenal states e.g. visual perception. Most representationalists endorse an unrestricted version of representationalism. According to the unrestricted version, for any state with phenomenal character that state’s phenomenal character reduces to its intentional content. Only this unrestricted version of representationalism is able to provide a general theory about the nature of phenomenal character, as well as offer a potential solution to the hard problem of consciousness. The successful reduction of the phenomenal character of a state to its intentional content would provide a solution to the hard problem of consciousness once a physicalist account of intentionality is worked out.

Problems for the Unrestricted Version

When arguing against the unrestricted version of representationalism people will often bring up phenomenal mental states that appear to lack intentional content. The unrestricted version seeks to account for all phenomenal states. Thus, for it to be true, all states with phenomenal character must have intentional content to which that character is reduced. Phenomenal states without intentional content therefore serve as a counterexample to the unrestricted version. If the state has no intentional content its phenomenal character will not be reducible to that state’s intentional content, for it has none to begin with.

A common example of this kind of state are moods. Moods are states with phenomenal character that are generally thought to not be directed at anything in particular. Moods are thought to lack directedness, unlike emotions, which are typically thought to be directed at particular things e.g. you are mad at your sibling, you are afraid of a dangerous animal. People conclude that because moods are undirected they are also nonintentional i.e. they lack intentionality or aboutness. Because they are not directed at anything they are not about anything. Because they lack intentionality they will lack any intentional content. Lacking intentional content their phenomenal character will not be reducible to intentional content, refuting the representational doctrine.

Though emotions are typically considered as having directedness and intentionality this idea has also been called into question. One might point to emotions a person all of a sudden experiences that do not appear to be directed at or about anything in particular. Emotions elicited by listening to music are another potential example of undirected, nonintentional emotions. Emotions aroused in this way do not seem to necessarily be about anything, including the music that arouses them.

Responses

In response to this objection a proponent of representationalism might reject the undirected nonintentionality of moods, and attempt to identify some intentional content they might plausibly be thought to possess. The proponent of representationalism might also reject the narrow conception of intentionality as being directed at a particular thing, arguing instead for a broader kind of intentionality.

There are three alternative kinds of directedness/intentionality one might posit for moods.

- Outward Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have a certain kind of outwardly focused representational content.

- Inward Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have a certain kind of inwardly focused representational content.

- Hybrid Directedness: What it is like to be in mood M is to have both a certain kind of outwardly focused representational content and a certain kind of inwardly focused representational content.

In the case of outward directedness moods might be directed at either the world as a whole, a changing series of objects in the world, or unbound emotion properties projected by people onto things in the world. In the case of inward directedness moods are directed at the overall state of a person’s body. In the case of hybrid directedness moods are directed at some combination of inward and outward things.

Further Objections

Even if one can identify some possible intentional content for moods we might still question whether that content is able to sufficiently capture the phenomenal character of the mood states they are a part of. Amy Kind contends that in the case of all the previously mentioned kinds of directedness (outward, inward, and hybrid) the intentional content supplied to the mood state is not capable of sufficiently capturing the phenomenal aspects of the mood states. In the case of inward directedness, the phenomenology of the mood does not seem tied to the state of one’s body, and even if one’s mood is reflected by the overall state of one’s body that person will not necessarily be aware of it, demonstrating the insufficiency of the intentional content to adequately capture the phenomenal aspects of the mood. In the case of outward directedness, the phenomenology of the mood and its intentional content do not seem to share the corresponding relation they should given that the phenomenal character is supposed to reduce to the intentional content. Hybrid directedness, if it can even get off the ground, faces the same objection.

Philosophers

There is a wide debate on what kinds of representations exist. There are several philosophers who bring about different aspects of the debate. Such philosophers include Alex Morgan, Gualtiero Piccinini, and Uriah Kriegel—though this is not an exhaustive list.

Alex Morgan

There are "job description" representations. That is representations that (1) represent something—have intentionality, (2) have a special relation—the represented object does not need to exist, and (3) content plays a causal role in what gets represented: e.g. saying "hello" to a friend,giving a glare to an enemy.

Structural representations are also important. These types of representations are basically mental maps that we have in our minds that correspond exactly to those objects in the world (the intentional content). According to Morgan, structural representations are not the same as mental representations—there is nothing mental about them: plants can have structural representations.

There are also internal representations. These types of representations include those that involve future decisions, episodic memories, or any type of projection into the future.

Gualtiero Piccinini

In Piccinini's forthcoming work, he discusses topics on natural and nonnatural mental representations. He relies on the natural definition of mental representations given by Grice (1957) where P entails that P. e.g. Those spots mean measles, entails that the patient has measles. Then there are nonnatural representations: P does not entail P. e.g. The 3 rings on the bell of a bus mean the bus is full—the rings on the bell are independent of the fullness of the bus—we could have assigned something else (just as arbitrary) to signify that the bus is full.

Uriah Kriegel

There are also objective and subjective mental representations. Objective representations are closest to tracking theories—where the brain simply tracks what is in the environment. If there is a blue bird outside my window, the objective representation is that of the blue bird. Subjective representations can vary person-to-person. For example, if I am colorblind, that blue bird outside my window will not appear blue to me since I cannot represent the blueness of blue (i.e. I cannot see the color blue). The relationship between these two types of representation can vary.

(a) Objective varies, but the subjective does not: e.g. brain-in-a-vat

(b) Subjective varies, but the objective does not: e.g. color-inverted world

(c) All representations found in objective and none in the subjective: e.g. thermometer

(d) All representations found in subjective and none in the objective: e.g. an agent that experiences in a void.

Eliminativists think that subjective representations don't exist. Reductivists think subjective representations are reducible to objective. Non-reductivists think that subjective representations are real and distinct.

The debates about mental representation do not end here. In fact, they lead to other discussions such as content of mental states, embodied cognition, consciousness, and phenomenology.

See also

- Representation in dynamical systems models of cognition

- Object of the mind

- Knowledge representation

- Perception

- Representative realism

- Condensation (psychology)

- Visual space

- Mental model

- Worldview

- Paradigm

- Mindset

- Set (psychology)

- Schema (psychology)

- Basic beliefs