Fetishism

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 18:12, 7 May 2008 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | [[Image:Marquis de Sade by H. Biberstein, 1866.jpg|thumb|left|200px|See [[sexual fetishism]], illustration: ''[[Portrait fantaisiste du marquis de Sade]]'']] | ||

| + | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| + | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | "[[World exhibition]]s were places of pilgrimage to the [[Commodity fetishism|fetish commodity]]." --''[[Arcades Project]]'' (1927 - 1940) by Walter Benjamin | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "If the [[Commodity fetishism|commodity was a fetish]], then [[Grandville]] was the tribal [[sorcerer]]." --''[[Arcades Project]]'' (1927 - 1940) by Walter Benjamin | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "[In] the religious world[,] the productions of the human brain appear as independent beings endowed with life, and enter into relation both with one another and the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men's hands. This I call the Fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour, so soon as they are produced as commodities." --''[[Das Kapital]]'' (1867) by Karl Marx | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "Everyone is more or less a [[fetishist]] in love." --''[[Le fétichisme dans l'amour]]'' (1887) by Alfred Binet | ||

| + | |} | ||

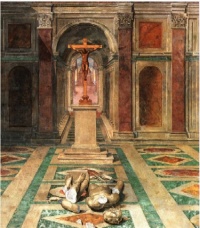

| + | [[Image:Tommaso.Laureti.Triumph.of.Christianity.jpg|right|thumb|200px|This page '''{{PAGENAME}}''' is part of the [[worship]] series.<br><Small>Illustration: ''[[Triumph of Christianity]]'' (detail) by Tommaso Laureti (1530-1602.)</small>]] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | :''This article concerns the concept of fetishism in [[anthropology]]. Separate articles are devoted to [[sexual fetishism]] and the Marxist concept of [[commodity fetishism]].'' | + | A '''fetish''' denotes something which is believed to possess, contain, or cause [[spiritual]] or [[magical]] powers; an [[amulet]] or a [[talisman]]. This meaning was popularized in anthropology by Charles de Brosses's ''[[Du culte des dieux fétiches]]'' (1760). A hundred years later the term was appropriated by Karl Marx in his ''[[Das Kapital]]'' (1867) to refer to [[commodity fetishism]] and twenty years later still, in ''[[Le fétichisme dans l'amour]]'' (1887) by Alfred Binet, the term began to refer to [[sexual fetishism]] provoked by [[object]]s or [[body parts]]. In common parlance, a fetish refers to an [[irrational]], or [[abnormal]] [[fixation]] or preoccupation. |

| + | This article concerns the concept of [[fetishism]] in [[anthropology]]. Separate articles are devoted to [[sexual fetishism]] and the Marxist concept of [[commodity fetishism]]. | ||

| - | A '''fetish''' (from [[French language|French]] ''fétiche''; from [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] ''feitiço''; from [[Latin]] ''facticius'', "artificial" and ''facere'', "to make") is an object believed to have [[supernatural]] [[power]]s, or in particular a [[man-made]] object that has power over [[other]]s. | + | ==Historiography (anthropology)== |

| + | The term "fetish" has evolved from an idiom used to describe a type of object created in the interaction between European travelers and Africans in the early modern period to an analytical term that played a central role in the perception and study of non-Western art in general and African art in particular. | ||

| - | ==History== | + | [[William Pietz]], who, in 1994, conducted an extensive ethno-historical study of the fetish, argues that the term originated in the coast of [[West Africa]] during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Pietz distinguishes between, on the one hand, actual African objects that may be called fetishes in Europe, together with the [[Emic_and_etic#Definitions|indigenous theories of them]], and on the other hand, "fetish", an idea, and an idea of a kind of object, to which the term above applies. |

| - | The concept was coined by [[Charles de Brosses]] in [[1757]], while comparing [[West Africa]]n religion to the [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]]al aspects of [[Ancient Egypt]]ian religion. He and other [[18th century]] scholars used the concept to apply [[evolution theory]] to [[religion]]. In de Brosses' theory of the evolution of religion, he proposed that fetishism is the earliest (most primitive) stage, followed by the stages of [[polytheism]] and [[monotheism]] and [[totemism]] to account for fetishism. | + | |

| - | Essentially, fetishism is attributing some kind of inherent value or powers to an object. For example, the person who sees magical or divine significance in a material object is mistakenly ascribing inherent value to some object which does not possess that value (hence Marx's commodity fetishism: belief that objects control us) | + | |

| - | In the [[19th century]], Tylor and McLennan held that the concept of fetishism allowed historians of religion to shift attention from the relationship between people and [[God]] to the relationship between people and material objects. They also held that it established models of [[causality|causal explanations]] of natural events which they considered false as a central problem in history and sociology. | + | According to Pietz, the [[post-colonial]] concept of "fetish" emerged from the encounter between Europeans and Africans in a very specific historical context and in response to African material culture. |

| + | |||

| + | He begins his thesis with an introduction to the complex history of the word: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>My argument, then, is that the fetish could originate only in conjunction with the emergent articulation of the ideology of the commodity form that defined itself within and against the social values and religious ideologies of two radically different types of noncapitalist society, as they encountered each other in an ongoing cross-cultural situation. This process is indicated in the history of the word itself as it developed from the late medieval Portuguese ''feitiço'', to the sixteenth-century pidgin ''Fetisso'' on the African coast, to various northern European versions of the word via the 1602 text of the Dutchman Pieter de Marees... The fetish, then, not only originated from, but remains specific to, the problem of the social value of material objects as revealed in situations formed by the encounter of radically heterogeneous social systems, and a study of the history of the idea of the fetish may be guided by identifying those themes that persist throughout the various discourses and disciplines that have appropriated the term. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Stallybrass concludes that "Pietz shows that the fetish as a concept was elaborated to demonize the supposedly arbitrary attachment of West Africans to material objects. The European subject was constituted in opposition to a demonized fetishism, through the disavowal of the object." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History (anthropology)== | ||

| + | Initially, the [[Portuguese people|Portuguese]] developed the concept of the fetish to refer to the objects used in religious practices by West African natives. The contemporary Portuguese ''feitiço'' may refer to more neutral terms such as charm, enchantment, or abracadabra, or more potentially offensive terms such as juju, witchcraft, witchery, conjuration or bewitchment. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The concept was popularized in Europe circa 1757, when [[Charles de Brosses]] used it in comparing [[West Africa]]n religion to the [[Magic (paranormal)|magical]] aspects of [[ancient Egyptian religion]]. Later, [[Auguste Comte]] employed the concept in his theory of the [[evolution theory|evolution]] of [[religion]], wherein he posited fetishism as the earliest (most primitive) stage, followed by [[polytheism]] and [[monotheism]]. However, [[ethnography]] and [[anthropology]] would classify some artifacts of monotheistic religions as fetishes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The eighteenth-century intellectuals who articulated the theory of fetishism encountered this notion in descriptions of "Guinea" contained in such popular voyage collections as Ramusio's ''Viaggio e Navigazioni'' (1550), de Bry's ''India Orientalis'' (1597), Purchas's ''Hakluytus Posthumus'' (1625), [[Awnsham Churchill|Churchill]]'s ''Collection of Voyages and Travels'' (1732), [[Thomas Astley|Astley]]'s ''A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels'' (1746), and Prevost's ''Histoire generale des voyages'' (1748). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The theory of fetishism was articulated at the end of the eighteenth century by [[G. W. F. Hegel]] in ''[[Lectures on the Philosophy of History]]''. According to Hegel, Africans were incapable of abstract thought, their ideas and actions were governed by impulse, and therefore a fetish object could be anything that then was arbitrarily imbued with imaginary powers. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the 19th and 20th centuries, Tylor and McLennan, historians of religion, held that the concept of fetishism fostered a shift of attention away from the relationship between people and [[God]], to focus instead on a relationship between people and material objects, and that this, in turn, allowed for the establishment of false models of [[causality]] for natural events. This they saw as a central problem historically and sociologically. | ||

| ==Practice== | ==Practice== | ||

| - | Theoretically, fetishism is present in all religions, but its use in the study of religion is derived from studies of traditional [[West Africa]]n religious beliefs, as well as [[Voodoo]], which is derived from those beliefs. | + | The use of the concept in the study of religion derives from studies of traditional [[West Africa]]n religious beliefs, as well as from [[West African Vodun|Voodoo]], which in turn derives from those beliefs. |

| - | [[Blood]] is often considered a particularly powerful fetish or ingredient in fetishes. In some parts of [[Africa]], the [[hair]] of white people was also considered powerful. | + | Fetishes were commonly used in some [[Native American religions]] and practices. For example, the [[bear]] represented the [[shaman]], the [[American Bison|buffalo]] was the provider, the [[mountain lion]] was the warrior, and the [[wolf]] was the pathfinder. |

| - | In addition to [[blood]], other objects and substances, such as [[bone]]s, [[fur]], [[claws]], [[feather]]s, [[water]] from certain places, certain types of [[plants]], and [[woods|wood]] are common fetishes in the traditions of cultures worldwide. | + | ==''Minkisi''== |

| + | Made and used by the [[Kongo people|BaKongo]] of western [[Zaire]], a ''[[nkisi]]'' (plural ''minkisi'') is a sculptural object that provides a local habitation for a spiritual personality. Though some ''minkisi'' have always been anthropomorphic, they were probably much less naturalistic or "realistic" before the arrival of the Europeans in the nineteenth century; Kongo figures are more naturalistic in the coastal areas than inland. As Europeans tend to think of spirits as objects of worship, idols become the objects of idolatry when worship was addressed to false gods. In this way, Europeans regarded ''minkisi'' as idols on the basis of false assumptions. | ||

| - | ==Other uses of the term "fetishism"== | + | Europeans often called ''nkisi'' "fetishes" and sometimes "[[Cult image|idols]]" because they are sometimes rendered in human form. Modern anthropology has generally referred to these objects either as "power objects" or as "charms". |

| - | *In the 19th century [[Karl Marx]] appropriated the term to describe [[commodity fetishism]] as an important component of [[capitalism]]. Nowadays, (commodity and capital) fetishism is a central concept of marxism | + | |

| - | *Later [[Sigmund Freud]] appropriated the concept to describe a form of [[paraphilia]] where the object of affection is an inanimate object or a specific part of a person; see [[sexual fetish]]. | + | |

| - | == See also == | + | In addressing the question of whether a ''nkisi'' is a fetish, William McGaffey writes that the Kongo ritual system as a whole, |

| + | <blockquote>bears a relationship similar to that which Marx supposed that "political economy" bore to capitalism as its "religion", but not for the reasons advanced by Bosman, the Enlightenment thinkers, and Hegel. The irrationally "animate" character of the ritual system's symbolic apparatus, including ''minkisi'', divination devices, and witch-testing ordeals, obliquely expressed real relations of power among the participants in ritual. "Fetishism" is about relations among people, rather than the objects that mediate and disguise those relations. | ||

| + | </blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Therefore, McGaffey concludes, to call a ''nkisi'' a fetish is to translate "certain Kongo realities into the categories developed in the emergent social sciences of nineteenth century, post-enlightenment Europe." | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | =='''Fetish''' may also refer to:== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Sexual=== | ||

| + | * [[Sexual fetishism]], a sexual attraction to objects or body parts of lesser sexual importance (or none at all) such as feet, toes or certain types of clothing | ||

| + | ** [[Racial fetishism]] | ||

| + | * [[Fetish subculture]], a social movement constructed around sexual fetishism | ||

| + | * [[Fetish magazine]], a type of erotic magazine | ||

| + | * [[Fetish art]] | ||

| + | ** [[List of fetish artists]] | ||

| + | * [[Fetish fashion]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Arts=== | ||

| + | * ''[[The Great Fetish]]'', a science fiction novel by L. Sprague de Camp | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Business=== | ||

| + | * [[Commodity fetishism]], a Marxist concept of valuation in capitalist markets | ||

| + | * ''[[Growth Fetish]]'', a 2003 book by Clive Hamilton advocating a zero-growth economy among "developed" nations | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Etymology== | ||

| + | From French ''fétiche'', from Portuguese ''feitiço'', from Latin ''[[factīcius]]'' (“[[artificial]]” and ''[[facere]]'', "to make"). | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[Boli (fetish)|Boli]] | ||

| + | *[[Cargo cult]] | ||

| * [[Idolatry]] | * [[Idolatry]] | ||

| * [[Animism]] | * [[Animism]] | ||

| Line 28: | Line 89: | ||

| * [[Taboo]] | * [[Taboo]] | ||

| * [[Conspicuous consumption]] | * [[Conspicuous consumption]] | ||

| - | * the book ''[[Growth Fetish]]'' | ||

| * [[Sexual fetishism]] | * [[Sexual fetishism]] | ||

| + | * ''[[The Power of Myth]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

"World exhibitions were places of pilgrimage to the fetish commodity." --Arcades Project (1927 - 1940) by Walter Benjamin "If the commodity was a fetish, then Grandville was the tribal sorcerer." --Arcades Project (1927 - 1940) by Walter Benjamin "[In] the religious world[,] the productions of the human brain appear as independent beings endowed with life, and enter into relation both with one another and the human race. So it is in the world of commodities with the products of men's hands. This I call the Fetishism which attaches itself to the products of labour, so soon as they are produced as commodities." --Das Kapital (1867) by Karl Marx "Everyone is more or less a fetishist in love." --Le fétichisme dans l'amour (1887) by Alfred Binet |

Illustration: Triumph of Christianity (detail) by Tommaso Laureti (1530-1602.)

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

A fetish denotes something which is believed to possess, contain, or cause spiritual or magical powers; an amulet or a talisman. This meaning was popularized in anthropology by Charles de Brosses's Du culte des dieux fétiches (1760). A hundred years later the term was appropriated by Karl Marx in his Das Kapital (1867) to refer to commodity fetishism and twenty years later still, in Le fétichisme dans l'amour (1887) by Alfred Binet, the term began to refer to sexual fetishism provoked by objects or body parts. In common parlance, a fetish refers to an irrational, or abnormal fixation or preoccupation. This article concerns the concept of fetishism in anthropology. Separate articles are devoted to sexual fetishism and the Marxist concept of commodity fetishism.

Contents |

Historiography (anthropology)

The term "fetish" has evolved from an idiom used to describe a type of object created in the interaction between European travelers and Africans in the early modern period to an analytical term that played a central role in the perception and study of non-Western art in general and African art in particular.

William Pietz, who, in 1994, conducted an extensive ethno-historical study of the fetish, argues that the term originated in the coast of West Africa during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Pietz distinguishes between, on the one hand, actual African objects that may be called fetishes in Europe, together with the indigenous theories of them, and on the other hand, "fetish", an idea, and an idea of a kind of object, to which the term above applies.

According to Pietz, the post-colonial concept of "fetish" emerged from the encounter between Europeans and Africans in a very specific historical context and in response to African material culture.

He begins his thesis with an introduction to the complex history of the word:

My argument, then, is that the fetish could originate only in conjunction with the emergent articulation of the ideology of the commodity form that defined itself within and against the social values and religious ideologies of two radically different types of noncapitalist society, as they encountered each other in an ongoing cross-cultural situation. This process is indicated in the history of the word itself as it developed from the late medieval Portuguese feitiço, to the sixteenth-century pidgin Fetisso on the African coast, to various northern European versions of the word via the 1602 text of the Dutchman Pieter de Marees... The fetish, then, not only originated from, but remains specific to, the problem of the social value of material objects as revealed in situations formed by the encounter of radically heterogeneous social systems, and a study of the history of the idea of the fetish may be guided by identifying those themes that persist throughout the various discourses and disciplines that have appropriated the term.

Stallybrass concludes that "Pietz shows that the fetish as a concept was elaborated to demonize the supposedly arbitrary attachment of West Africans to material objects. The European subject was constituted in opposition to a demonized fetishism, through the disavowal of the object."

History (anthropology)

Initially, the Portuguese developed the concept of the fetish to refer to the objects used in religious practices by West African natives. The contemporary Portuguese feitiço may refer to more neutral terms such as charm, enchantment, or abracadabra, or more potentially offensive terms such as juju, witchcraft, witchery, conjuration or bewitchment.

The concept was popularized in Europe circa 1757, when Charles de Brosses used it in comparing West African religion to the magical aspects of ancient Egyptian religion. Later, Auguste Comte employed the concept in his theory of the evolution of religion, wherein he posited fetishism as the earliest (most primitive) stage, followed by polytheism and monotheism. However, ethnography and anthropology would classify some artifacts of monotheistic religions as fetishes.

The eighteenth-century intellectuals who articulated the theory of fetishism encountered this notion in descriptions of "Guinea" contained in such popular voyage collections as Ramusio's Viaggio e Navigazioni (1550), de Bry's India Orientalis (1597), Purchas's Hakluytus Posthumus (1625), Churchill's Collection of Voyages and Travels (1732), Astley's A New General Collection of Voyages and Travels (1746), and Prevost's Histoire generale des voyages (1748).

The theory of fetishism was articulated at the end of the eighteenth century by G. W. F. Hegel in Lectures on the Philosophy of History. According to Hegel, Africans were incapable of abstract thought, their ideas and actions were governed by impulse, and therefore a fetish object could be anything that then was arbitrarily imbued with imaginary powers.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, Tylor and McLennan, historians of religion, held that the concept of fetishism fostered a shift of attention away from the relationship between people and God, to focus instead on a relationship between people and material objects, and that this, in turn, allowed for the establishment of false models of causality for natural events. This they saw as a central problem historically and sociologically.

Practice

The use of the concept in the study of religion derives from studies of traditional West African religious beliefs, as well as from Voodoo, which in turn derives from those beliefs.

Fetishes were commonly used in some Native American religions and practices. For example, the bear represented the shaman, the buffalo was the provider, the mountain lion was the warrior, and the wolf was the pathfinder.

Minkisi

Made and used by the BaKongo of western Zaire, a nkisi (plural minkisi) is a sculptural object that provides a local habitation for a spiritual personality. Though some minkisi have always been anthropomorphic, they were probably much less naturalistic or "realistic" before the arrival of the Europeans in the nineteenth century; Kongo figures are more naturalistic in the coastal areas than inland. As Europeans tend to think of spirits as objects of worship, idols become the objects of idolatry when worship was addressed to false gods. In this way, Europeans regarded minkisi as idols on the basis of false assumptions.

Europeans often called nkisi "fetishes" and sometimes "idols" because they are sometimes rendered in human form. Modern anthropology has generally referred to these objects either as "power objects" or as "charms".

In addressing the question of whether a nkisi is a fetish, William McGaffey writes that the Kongo ritual system as a whole,

bears a relationship similar to that which Marx supposed that "political economy" bore to capitalism as its "religion", but not for the reasons advanced by Bosman, the Enlightenment thinkers, and Hegel. The irrationally "animate" character of the ritual system's symbolic apparatus, including minkisi, divination devices, and witch-testing ordeals, obliquely expressed real relations of power among the participants in ritual. "Fetishism" is about relations among people, rather than the objects that mediate and disguise those relations.

Therefore, McGaffey concludes, to call a nkisi a fetish is to translate "certain Kongo realities into the categories developed in the emergent social sciences of nineteenth century, post-enlightenment Europe."

Fetish may also refer to:

Sexual

- Sexual fetishism, a sexual attraction to objects or body parts of lesser sexual importance (or none at all) such as feet, toes or certain types of clothing

- Fetish subculture, a social movement constructed around sexual fetishism

- Fetish magazine, a type of erotic magazine

- Fetish art

- Fetish fashion

Arts

- The Great Fetish, a science fiction novel by L. Sprague de Camp

Business

- Commodity fetishism, a Marxist concept of valuation in capitalist markets

- Growth Fetish, a 2003 book by Clive Hamilton advocating a zero-growth economy among "developed" nations

Etymology

From French fétiche, from Portuguese feitiço, from Latin factīcius (“artificial” and facere, "to make").

See also

- Boli

- Cargo cult

- Idolatry

- Animism

- Totemism

- Taboo

- Conspicuous consumption

- Sexual fetishism

- The Power of Myth