Anthropomorphism

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"But if cattle and horses and lions had hands [...]" --Xenophanes |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

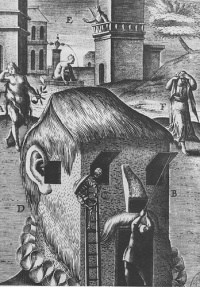

Anthropomorphism, or personification is the attribution of uniquely human characteristics and qualities to nonhuman beings, inanimate objects, or natural or supernatural phenomena. Animals, forces of nature, and unseen or unknown sources of chance are frequent subjects of anthropomorphosis. The term is derived from two Greek words, ἄνθρωπος (anthrōpos), meaning human, and μορφή (morphē), meaning shape or form. The suffix '-ism' originates from the morpheme -ισμός or -ισμα in the Greek language.

It is a common and seemingly natural tendency for humans to perceive inanimate objects as having human characteristics, one which some suggest provides a window into the way in which humans perceive themselves. Common examples of this tendency include naming cars or begging machines to work. In 1953, the U.S. government began assigning hurricanes names; initially the names were feminine, and shortly thereafter masculine names were introduced.

Contents |

In religion and mythology

In religion and mythology, anthropomorphism refers to the perception of a divine being or beings in human form, or the recognition of human qualities in these beings. Many mythologies are concerned with anthropomorphic deities who express human characteristics such as jealousy, hatred, or love. The Greek gods, such as Zeus and Apollo, were often depicted in human form exhibiting human traits. Anthropomorphism in this case is referred to as anthropotheism.

Numerous sects throughout history have been called anthropomorphites attributing such things as hands and eyes to God, including a sect in Egypt in the 4th century, and an heretical, 10th-century sect, who literally interpreted Book of Genesis chapter 1, verse 27: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them."

From the perspective of adherents of religions in which humans were created in the form of the divine, the phenomenon may be considered theomorphism, or the giving of divine qualities to humans.

Criticism

The Greek philosopher Xenophanes (570–480 BC) said that "the greatest god" resembles man "neither in form nor in mind." Anthropomorphism of God is rejected by Judaism and Islam, which both believe that God is beyond human limits of physical comprehension. Judaism's rejection grew after the advent of Christianity until becoming codified in 13 principles of Jewish faith authored by Maimonides in the 12th Century.

In his book Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion, Stewart Elliott Guthrie theorizes that all religions are anthropomorphisms that originate due to the brain's tendency to detect the presence or vestiges of other humans in natural phenomena.

In literature

Ancient literature

Anthropomorphism is a well established literary device from early times. Aesop's Fables, a collection of short tales written by the ancient Greek citizen Aesop, make extensive use of anthropomorphism, in which animals and weather are used to illustrate simple moral lessons. The books Panchatantra (The Five Principles) and The Jataka Tales employ anthropomorphised animals to illustrate various principles of life.

Children's literature

Anthropomorphism is commonly employed in books for children, such as those by Lewis Carroll, Roald Dahl, Brian Jacques, C.S. Lewis, and Beatrix Potter. Rev. W. Awdry's Railway Series depicts steam locomotives with human-like faces and personalities which leads to the popular tv series.

Fantasy

However, anthropomorphism is not exclusively used as a device in children's literature: Terry Pratchett is notable for having several anthropomorphic characters in his Discworld series, the best-known of which is the character Death. Piers Anthony also wrote a series regarding the seven Incarnations of Immortality, which are Death, Time, Fate, War, Nature, Evil, and Good. Neil Gaiman is notable for anthropomorphising seven aspects of the world in his series Sandman, named the Endless: Destiny, Death, Dream, Destruction, Desire, Despair, and Delirium. Perhaps most famously, George Orwell converted several key actors in the Russian Revolution into anthropomorphic animals in his satire Animal Farm. Garry Kilworth's Welkin Weasels series reverses the idea of carnivores as villains in children's literature. In Art Spiegelman's Maus, a graphic novel about The Holocaust, different races are portrayed as different animals - the Jews as mice, Germans as cats and Poles as pigs, for example.

Television

Anthropomorphism plays a role in some popular films and TV shows. The Griffin family of Fox's hit comedy Family Guy has an anthropomorphic dog named Brian, and the spin-off of Family Guy, The Cleveland Show, has a family of anthropomorphic bears. From the popular British animated short films Wallace and Gromit comes Gromit, the beloved anthropomorphic dog of Wallace. Almost all characters from Nickelodeon's hit show SpongeBob SquarePants are anthropomorphic in nature, with the exception of the characters Patchy the Pirate, Mermaidman and Barnacleboy, and the Flying Dutchman. Additionally, many of the films made by Pixar Animation Studios center around anthropomorphisms, including cars(Cars), fish(Finding Nemo), aliens, monsters, dogs and many others. The Character Birdo from the hit gaming series, Super Mario is also an anthropomorphic species.

Art history

Claes Oldenburg

Claes Oldenburg's soft sculptures are commonly described as anthropomorphic. Depicting common household objects, Oldenburg's sculptures were considered Pop Art. Reproducing these objects, often at a greater size than the original, Oldenburg created his sculptures out of soft materials. The anthropomorphic qualities of the sculptures were mainly in their sagging and malleable exterior which mirrored the not so idealistic forms of the human body. In "Soft Light Switches" Oldenburg creates a household light switch out of Vinyl. The two identical switches, in a dulled orange, insinuate nipples. The soft vinyl references the aging process as the sculpture wrinkles and sinks with time.

Minimalism

In the essay "Art and Objecthood", Michael Fried makes the case that "Literalist art" (Minimalism) becomes theatrical by means of anthropomorphism. The viewer engages the minimalist work, not as an autonomous art object, but as a theatrical interaction. Fried references a conversation in which Tony Smith answers questions about his "six-foot cube, Die."

Q: Why didn't you make it larger so that it would loom over the observer? A: I was not making a monument. Q: then why didn't you make it smaller so that the observer could see over the top? A: I was not making an object.

Fried implies an anthropomorphic connection by means of "a surrogate person-that is, a kind of statue."

The minimalist decision of "hollowness" in much of their work, was also considered by Fried, to be "blatantly anthropomorphic." This "hollowness" contributes to the idea of a separate inside; an idea mirrored in the human form. Fried considers the Literalist art's "hollowness" to be "biomorphic" as it references a living organism.

Post Minimalism

Curator Lucy Lippard's Eccentric Abstraction show, in 1966, sets up Briony Fer's writing of a post minimalist anthropomorphism. Reacting to Fried's interpretation of minimalist art's "looming presence of objects which appear as actors might on a stage", Fer interprets the artists in Eccentric Abstraction to a new form of anthropomorphism. She puts forth the thoughts of Surrealist writer Roger Caillois, who speaks of the "spacial lure of the subject, the way in which the subject could inhabit their surroundings." Caillous uses the example of an insect who "through camouflage does so in order to become invisible... and loses its distinctness." For Fer, the anthropomorphic qualities of imitation found in the erotic, organic sculptures of artists Eva Hesse and Louise Bourgeois, are not necessarily for strictly "mimetic" purposes. Instead, like the insect, the work must come into being in the "scopic field... which we cannot view from outside."(Briony, Objects Beyond Objecthood)

See also

- Aniconism: antithetic concept

- Animism

- Anthropic principle

- Anthropocentrism

- Anthropology

- Funny animal

- Great Chain of Being

- Humanoid

- List of anthropomorphic personifications

- Moe anthropomorphism

- National personification

- Pathetic fallacy

- Stereotypes of animals

- Talking animals in fiction

- Zoomorphism

Examples