Decadent movement

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"I like this word decadent; all shimmering and purple and gold" --Paul Verlaine "Turning to the critics for the definition of Decadence is much like listening to the famous orchestra of the King of Siam, where each musician plays the way he wants to and without paying any attention to the score." --Legend of the Decadents (1927) by Gustave Leopold van Roosbroeck "Barbaric in its profusion, violent in its emphasis, wearying in its splendor, [À rebours] is - especially in regard to things seen - extraordinarily expressive, with all the shades of a painter's palette. Elaborately and deliberately perverse, it is in its very perversity that Huysmans' work - so fascinating, so repellent, so instinctively artificial - comes to represent, as the work of no other writer can be said to do, the main tendencies, the chief results, of the Decadent movement in literature."--"The Decadent Movement in Literature" (1893) by Arthur Symons "Decadent literature!— Empty words which we often hear fall, with the sonority of a deep yawn, from the mouths of those unenigmatic sphinxes who keep watch before the sacred doors of classical Aesthetics." --incipit "Notes nouvelles sur Edgar Poe" (1857) by Baudelaire |

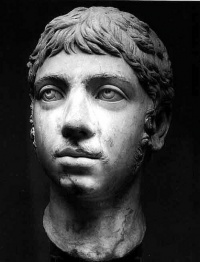

Illustration: Elagabalus, a Roman emperor known for perverse and decadent behavior. Due to these associations with Roman decadence, Elagabalus became something of a hero to the Decadent movement in the late 19th century. Characterizing him and other historical persons in antiquity as "psychopaths" — for example, the five "mad emperors" of ancient Rome: Caligula, Nero, Domitian, Commodus, and Elagabalus — is however a retroactive speculation premised on a decidedly modern view of human nature and individual psychology. This modern view did not start to develop until the Late Middle Ages, reaching full fruition in the Enlightenment and Romantic movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

In fin de siècle Europe, the Decadents were a group of artists who rejected the Modernist trend towards realism and continued the Romantic tradition of irrationalism. The term decadent was a term of abuse by French critics which the decadents adopted triumphantly. The Symbolist and Aesthetic movements were contemporary and similar. The classic novel from this group is Joris-Karl Huysmans's Against Nature, often seen as the first great Decadent work, though others attribute this honor to Baudelaire's poetry.

In Britain the leading figures associated with the Decadent movement were Oscar Wilde, Aubrey Beardsley and some artists and writers associated with The Yellow Book. In the United States, the brothers Edgar and Francis Saltus wrote decadent fiction and poetry.

Wilde paid a high price for his "decadence" by being sent to jail for allegations of homosexuality. By the first decade of the 20th century, this movement was over, some of its influences still lingering on in Art Nouveau.

Contents |

Context

In 19th century European and especially French literature, decadence was the name given, first by hostile critics, and then triumphantly adopted by some writers themselves, to a number of late nineteenth century fin de siècle writers who were associated with Symbolism or the Aesthetic movement and who relished artifice over the earlier Romantics' naïve view of nature (see Rousseau). Some of these writers were influenced by the tradition of the Gothic novel and by the poetry and fiction of Edgar Allan Poe.

This concept of decadence dates from the eighteenth century, especially from Montesquieu, and was taken up by critics as a term of abuse after Désiré Nisard (Études de mœurs et de critique sur les poètes latins de la décadence) used it against Victor Hugo and Romanticism in general. A later generation of Romantics, such as Théophile Gautier and Charles Baudelaire took the word as a badge of pride, as a sign of their rejection of what they saw as banal "progress". Baudelaire famously begins the essay "Notes nouvelles sur Edgar Poe" (1857) with the exclamation: "Literature of decadence!" and Gautier praised decadence in his 1868 preface to Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal.

In the 1880s a group of French writers referred to themselves as decadents. The classic novel from this group is Joris-Karl Huysmans' Against Nature, often seen as the first great Decadent work, though others attribute this honor to Baudelaire's works. In Britain the leading figure associated with the Decadent movement was Oscar Wilde.

As a literary movement, Decadence is now regarded as a transition between Romanticism and Modernism.

The Symbolist movement has frequently been confused with the decadent movement. Several young writers were derisively referred to in the press as "decadent" in the mid 1880s. Jean Moréas' manifesto was largely a response to this polemic. A few of these writers embraced the term while most avoided it. Although the esthetics of Symbolism and Decadence can be seen as overlapping in some areas, the two remain distinct.

Criticisms by British social realists

In 1869 Matthew Arnold set a cultural agenda in his book Culture and Anarchy. His views represented one of two polar opposites which would be in struggle against each other for many years to come. The other side of the struggle would be represented by the Aesthetic, Symbolist or Decadent movement. The chief participants in the cultural opposition at this time included, on the so-called decadent side French poets like Jean Moréas, Paul Verlaine, Tristan Corbière, Arthur Rimbaud, Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and, in Britain, the Irish writer Oscar Wilde. On the other side were Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin and the tendency amongst the arts toward a utilitarian, constructive and educational ethic. The views of Matthew Arnold and John Ruskin inspired the Arts and Crafts movement and William Morris. This dispute (art for art's sake versus art for the common good) would continue throughout the remainder of the 19th century and much of the 20th.

Femme fatale trope

In fin-de-siècle decadence, Oscar Wilde re-invented the femme fatale in the play Salome: she manipulates her lust-crazed uncle, King Herod, with her enticing Dance of the Seven Veils (Wilde's invention) to agree to her imperious demand: bring me the head of John the Baptist. Later, Salome was the subject of an opera by Strauss, was popularized on stage, screen, and peep-show booth in countless reincarnations.

Another enduring icon of glamour, seduction, and moral turpitude is Margaretha Geertruida, 1876–1917. While working as an exotic dancer, she took the stage name Mata Hari. Although she may have been innocent, she was accused of German espionage and was put to death by a French firing squad. After her death she became the subject of many sensational films and books.

Artists of the decadent movement

- Jules Amédée Barbey d'Aurevilly

- Gabriele d'Annunzio

- Charles Pierre Baudelaire

- Franz von Bayros

- Aubrey Beardsley

- Remy de Gourmont

- Ernest Dowson

- J. K. Huysmans

- Comte de Lautréamont

- Guy de Maupassant

- Gustave Moreau

- Edvard Munch

- Rachilde

- Odilon Redon

- Arthur Rimbaud

- Gérard de Nerval

- Georges Rodenbach

- Félicien Rops

- Octave Mirbeau

- Franz von Stuck

- Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam

- Oscar Wilde

- Eric Stenbock

- Algernon Swinburne

- Arthur Symons

Bibliography

- Legend of the Decadents (1927) by Gustave Leopold van Roosbroeck

- The Romantic Agony (1930) by Mario Praz

- Five Faces of Modernity (1977) by Matei Calinescu

- The Sense of Decadence in Nineteenth-Century France (1964) by K. W. Swart

- Dreamers of Decadence (1969) by Philippe Jullian

See also

- Quelques œuvres du décadentisme

- Quotations on Décadentisme

- Decadence: a chronology

- The decadent movement in the United States

- Era: 1880s - 1890s

- Theorists: Symbolist Manifesto (1886) - Jean Moréas - Anatole Baju - Paul Bourget

- Precursors: Charles Baudelaire - Théophile Gautier - Edgar Allan Poe - Romanticism - Gothic novel

- Influential to: deviant modernism - Surrealism

- Contemporary art movements: Aesthetic movement - Symbolist movement

- Tropes: art for art's sake - dandyism - degeneration - Europe - fin de siècle - Modernism - cultural pessimism - Romanticism

- Decadence

- I love this word decadence

- 'Decadents and Aesthetes' by Max Nordau

- I came too late into a world too old

- I like this word decadent; all shimmering and purple and gold

- decadent dicta

Key works

- Against Nature (1884) by Joris-Karl Huysmans

- Bruges-la-Morte (1892) - Georges Rodenbach

- Gorgon and the Heroes (1897) - Giulio Aristide Sartorio

- Histoires de masques (1900) - Jean Lorrain