Fictional portrayals of psychopaths in film

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"One of the glories of Los Angeles is its modernist residential architecture, but Hollywood movies have almost systematically denigrated this heritage by casting many of these houses as the residences of movie villains."--Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) by Thom Andersen |

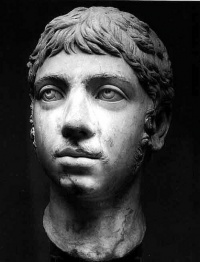

Illustrated by the head of Elagabalus, one of the five "mad emperors" of ancient Rome

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

This page is about fictional portrayals of psychopaths in film. Its predecessor was fictional portrayals of psychopaths in literature.

Notes

Deceptively charming psychopathic characters

The fictional psychopathic charm is somewhat at odds with the personal style of the clinically defined, charismatic psychopath . The latter are more likely to be rigid, controlling, impulsive, disorganized, short-sighted and violent. As a result, the volatile behavior and unstable affective pattern of the clinical psychopathic personality often bears little resemblance to the artful, wry charm, and enigmatic personae of the classic screen villains listed below:

- Danny in Night Must Fall (Robert Montgomery in 1937 version; Albert Finney in 1964 version)

- Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt)

Note: In the film it is obliquely suggested that Uncle Charlie's murderous behavior may actually be caused by frontal lobe disorder, also known as Pseudopsychopathic Personality Disorder.

- Harry Lime (Orson Welles in The Third Man)

- Bruno Anthony (Robert Walker in Strangers on a Train)

- Reverend Harry Powell (Robert Mitchum in The Night of the Hunter)

- Bud Corliss (Robert Wagner in A Kiss Before Dying; Matt Dillon in 1991 version)

- Tom Ripley (Alain Delon in Plein Soleil; Dennis Hopper in The American Friend; Matt Damon in The Talented Mr. Ripley; John Malkovich in Ripley's Game; and Barry Pepper in Ripley Under Ground)

- Prince Prospero (Vincent Price in The Masque of the Red Death)

Note: A number of Vincent Price villains such as his Matthew Hopkins in Witchfinder General and his titular protagonist in The Abominable Dr. Phibes also qualify as deceptively charming psychopaths. Some of Price's broader characterizations, like Nicholas Medina in The Pit and the Pendulum, would fall into the category of burlesque psychopathic characters.

- "The Jackal" (Edward Fox in The Day of the Jackal; Bruce Willis in The Jackal)

- Noah Cross (John Huston in Chinatown)

- Richard Vickers (Leslie Nielsen in Creepshow)

- O'Brien (Richard Burton in Nineteen Eighty-Four)

- Max Zorin (Christopher Walken in A View to a Kill)

- Jack Forrester (Jeff Bridges in Jagged Edge)

- Jason Dean (Christian Slater in Heathers)

- Peter McCabe (Michael Keaton in Desperate Measures)

- Dennis Peck (Richard Gere in Internal Affairs)

- Alex (Rob Lowe in Bad Influence)<ref>Template:Cite book</ref>

- Graham Marshall (Michael Caine in A Shock to the System)

- Francis Urquhart (Ian Richardson in House of Cards, To Play the King, and The Final Cut)

- Roger "Verbal" Kint, a.k.a. "Keyser Söze" (Kevin Spacey in The Usual Suspects)

- David McCall (Mark Wahlberg in Fear)

- Steven Taylor (Michael Douglas in A Perfect Murder)

- Jim Profit (Adrian Pasdar on the Fox-TV series Profit)

- Ryan O'Reily (Dean Winters on the HBO series, Oz)

- Ted Crawford (Anthony Hopkins in Fracture)

Explicitly morbid psychopathic characters

- See morbid

By the same token, the disordered narcissism and crudely aggressive personal style of the psychopath (also referred to as a sociopath or having an antisocial personality disorder) rarely resembles the cool self-possession and unflappable personal style present in explicitly morbid fictional characters. They are often presented as somewhat unrealistic, melodramatic cardboard villains and anti-heroes and are typically, but not necessarily, self-consciously "smooth", unctuous characters who cultivate an image of competence, professionalism and respectability. Unlike deceptively charming types, however, they are played straight and without any intrinsic comic or satiric irony based on received notions of amiability and familiarity.

Suffice to say, as a general rule, these explicitly morbid types do not come across as faintly likable or perversely amusing to the audience or to any of the other fictional characters that they share the screen with. However, their grimly determined, imperturbable style and methodical efficiency may afford occasional moments of deadpan humor and satire — in this sense, the fictional type of the explicitly morbid psychopath anticipates, and indeed shares, many of the same characteristics as the postmodern psychopath. On the other hand, the personal style of explicitly morbid psychopathic characters isn't as cartoonishly exaggerated as that of burlesque psychopaths and supervillains.

Examples of this explicitly morbid type of fictional psychopath include:

- Dr. Christian Szell (Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man)

- Dr. Josef Mengele (Gregory Peck in The Boys from Brazil)

- Dr. John Leslie Stevenson, a.k.a. "Jack the Ripper" (David Warner in Time After Time)

- Dr. Charles Henry Moffett (David Hemmings in Airwolf)

- Benson (Harvey Keitel in Saturn 3)

- Ben Childress (John Cassavetes in The Fury)

- Castor Troy (Nicolas Cage in Face/Off)

- Dr. Robert Elliott (Michael Caine in Dressed to Kill)

- Burke, a.k.a. "The Liberty Bell Strangler" (John Lithgow in Blow Out)

- Tommy Ray Glatman (David Patrick Kelly in Dreamscape)

- Piter de Vries (Brad Dourif in Dune, the 1984 film version; Jan Unger in the 2000 TV miniseries)

- Baron Frankenstein (Sting in The Bride)

- Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe in To Live and Die in L.A.)

- Jimmy Jump (Laurence Fishburne in King of New York)

- John Ryder (Rutger Hauer in The Hitcher)

- Mortwell (Michael Caine in Mona Lisa)

- Frank Nitti (Billy Drago in The Untouchables)

- Carter Hayes (Michael Keaton in Pacific Heights)

- Frederick "Junior" Frenger (Alec Baldwin in Miami Blues)

- Dr. Zachary Smith (Gary Oldman in Lost in space)

- Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins in The Silence of the Lambs; Hannibal; and Red Dragon; also Brian Cox in Manhunter and Gaspard Ulliel in Hannibal Rising)

- Mr. Blonde/Vic Vega (Michael Madsen in Reservoir Dogs)

- Mitch Leary (John Malkovich in In the Line of Fire)

- Johnny Ringo (Michael Biehn in Tombstone)

- Joshua Shapira (Tim Roth in Little Odessa)

- Jonathan Doe (Kevin Spacey in Se7en)

- Bob Wolverton (Kiefer Sutherland in Freeway)

- Aaron Stampler (Edward Norton in Primal Fear)

- "The Teacher" (Alec Baldwin in The Juror)

- "The Caller" (Kiefer Sutherland in Phone Booth)

- David McCall (Mark Wahlberg in Fear)

- Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stormare in Fargo)

- Peter and Paul (Frank Giering and Arno Frisch in Funny Games)

- Edgler Vess (John C. McGinley on the Fox-TV film Intensity)

- Chris Keller (Christopher Meloni on the HBO series, Oz)

- Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale in American Psycho)

- Detective Norman Stansfield (Gary Oldman in Léon)

- Walter Finch (Robin Williams in Insomnia)

- Francis Dolarhyde (Tom Noonan in Manhunter, Ralph Fiennes in Red Dragon)

- Alonzo Harris (Denzel Washington in Training Day)

- Theodore "T-Bag" Bagwell (Robert Knepper on the Fox-TV series Prison Break)

- Max Parry (Kevin Howarth in The Last Horror Movie)

- The Carver (Bruno Campos on the FX series Nip/Tuck)

- Arthur Burnes (Danny Huston in The Proposition)

- Dexter Morgan (Michael C. Hall on the Showtime series Dexter)

Comedic psychopathic characters

Burlesque psychopathic characters

Clearly fictional psychopathic personalities can be found in black comedy, melodrama, satire, and even semi-pornographic exploitation movies, with characters such as Charlie Chaplin as the eponymous anti-hero of the 1947 murder farce, Monsieur Verdoux (based on the actual case of the French "Bluebeard" killer, Henri Désiré Landru); Lee Marvin as the cartoonishly over-the-top outlaw in John Ford's famed elegiac 1962 western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance; and Tura Satana as the fiercely violent, sociopathic lesbian go-go dancer and gang-leader, Varla, in Russ Meyer's 1965 cult classic, Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!.

In the musical genre, Steve Martin's sadistic biker dentist, Orin Scrivello, D.D.S., in the 1986 film of Little Shop of Horrors, is yet another example of a comedic psychopathic character. (This buffoonish brute also presents verifiable traits of a clinical sociopath when he sings of how he enjoyed abusing animals as a child.)

Professor Ratigan, the cultured and sophisticated evil genius from Disney's Basil the Great Mouse Detective, also from 1986, is a comedic psychopathic character loosely based on Professor Moriarty.

A more recent example is Tim Roth's performance as the effete, gleefully treacherous and ribald Archibald Cunningham in the 1993 film of the eighteenth-century Walter Scott adventure romance, Rob Roy, which sketches the psychopath in the campy style of outsized stock villainy characteristic of burlesque.

In the anime Fullmetal Alchemist, the character Barry the Chopper is a serial killer who targets only women. Initially he is presented as a sadistic butcher who obsessed with using his blade to return people to their "most basic building blocks," and he leaves his victims bodies in public areas so that everyone could see. However, in later appearances Barry is presented as a more comedic villain who is easily excited and tends to act in a ridiculous manner.

Other burlesque psychopathic characters include:

- The Queen/Witch (voiced by Lucille La Verne in the 1937 animated film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs)

- The Wicked Witch of the West (Margaret Hamilton in The Wizard of Oz)

- Maleficent (voiced by Eleanor Audley in the 1959 animated film, Sleeping Beauty)

- Professor Ratigan (voiced by Vincent Price in the 1986 animated film Basil the Great Mouse Detective)

- Cruella De Vil (voiced by Betty Lou Gerson in the 1961 animated film, One Hundred and One Dalmatians, and played by Glenn Close in the 1996 live-action film, 101 Dalmatians, and its 2000 sequel, 102 Dalmatians)

- Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Kenneth McMillan in Dune, the 1984 film version; Ian McNeice in the 2000 TV miniseries)

- The Beast Rabban (Paul Smith in Dune, the 1984 film version; László Imre Kish in the 2000 TV miniseries)

- Feyd-Rautha (Sting in Dune, the 1984 film version; Matt Keeslar in the 2000 TV miniseries)

- Dr. Carl Hill (David Gale in Re-Animator)

- The Kurgan (Clancy Brown in Highlander)

- Edmund Blackadder (Rowan Atkinson in the period-set British comedy television series, Blackadder)

- Queen Bavmorda (Jean Marsh in Willow)

- Sheriff of Nottingham (Alan Rickman in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves)

- Sideshow Bob (voiced by Kelsey Grammer on the animated American television series, The Simpsons)

Note: An eccentric and snobbish homicidal clown with a taste for Gilbert and Sullivan musicals, the character of Sideshow Bob was probably inspired by serial child killer John Wayne Gacy.

Supervillain psychopathic characters

In a similar way, comic book-inspired movie supervillains such as Gene Hackman and Kevin Spacey as Lex Luthor in Superman and Superman Returns, and Jack Nicholson as the Joker in Batman, also qualify as comedic psychopathic characters (although it is to be noted that certain interpretations of the Joker in the comic book series depict him more in the manner of the postmodern psychopath). With their wild antics and extravagant crimes, supervillains often make comic stooges out of their straight-arrow, stiff-backed superhero nemeses.

Even Mike Myers as the absurd, pompous Dr. Evil, an effete megalomaniac forever plotting world domination in the Austin Powers movies, is but a parodic pastiche of the preposterously well-financed and well-equipped psychopathic supervillains (both smooth and comedic) that appear in the James Bond series, such as Ernst Stavro Blofeld, Dr. Julius No, Auric Goldfinger, Emilio Largo, Scaramanga, Karl Stromberg, Hugo Drax, Max Zorin, and Le Chiffre.

Notable henchmen in the Bond series who qualify as supervillain psychopathic characters include the lesbian spymistress Rosa Klebb, the steel-eyed assassin Red Grant (who is described as a "paranoiac psychopath"), the lethal Korean manservant Oddjob, the femme fatale Fiona Volpe, the bionically enhanced strongman Jaws, and the Amazon murderess May Day. Robert Shaw's portrayal of the affectless blond killer, Red Grant, in From Russia with Love, is probably the closest the Bond movies have come to depicting a psychopathic personality with a plausible degree of clinical accuracy.

Zim, the titular character in the Nickelodeon animated series, Invader Zim, is also a parody of the supervillain; his comic absurdity is tempered by moments of genuine malice and destructiveness.

Postmodern psychopathic characters

Dystopian psychopathic characters

Notable antecedents to the postmodern fictional psychopath are featured in dystopian science fiction, particularly in the genre's treatment of speculative themes like brainwashing and artificial intelligence.

The character of Dr. Benway, a perverse, power-seeking, drug-addicted surgical artist in William S. Burroughs' experimental stream-of-consciousness dystopia, Naked Lunch (1959), and other writings, exhibits distinctive psychopathic personality traits such as pathological selfishness and a depraved indifference towards the wellbeing of others — most notably his patients. Among his other activities, Benway is an illegal drug pusher and manufacturer. At one point, he is reduced to performing subway abortions after his medical license is revoked.

In the often shifting context of the fragmented — and often hallucinatory — narrative, Dr. Benway serves as a satiric personification of what Burroughs perceives as the ruthless, parasitic amorality of the American healthcare system and the medico-pharmaceutical industry at large. The primary incentive of these technocratic corporate entities is a calculated and thoroughgoing industrialized perversion of the Hippocratic Oath — profit based on a legalized monopoly of the drug trade and mind control.

A Clockwork Orange (1962)

A prime example of this type of dystopian fictional psychopath is the crafty, wicked and exuberantly "ultraviolent" juvenile delinquent Alex in Anthony Burgess' darkly ironic fable, A Clockwork Orange.

Throughout the course of the story, Alex — who archly narrates his own story and takes the reader/audience into his confidence in the manner of Swift's Gulliver — reveals himself to be completely devoid of any moral agency or free will as it is defined by either the Kantian system of transcendental idealism or the Sartrean model of existential humanism.

However, the implications of this critical irony in the book are not clarified in Stanley Kubrick's 1971 film featuring Malcolm McDowell's iconic performance as Alex.

In the book, the state-sanctioned behavior modification program — "the Ludovico technique" — which is designed to stifle, through artificially induced Pavlovian aversion therapy, any aggressive criminal tendencies in the subject's personality, suggests a fanciful panacea "cure" for psychopathy. But when Alex recovers from having been a guinea pig in the state's heavy-handed experiments in social engineering, and he is restored to his original mad, bad delinquent self once again, he realizes that he had essentially been a kind of automaton all along, albeit an anti-social one.

Burgess' implicit contention is that Alex's anarchistic, thrill-seeking creed of "ultraviolence" does not constitute true freedom and self-actualization but is rather a regression to a primitive kind of automatism. This innately corrupt and altogether psychopathic belief system is a symptom of the anomic Weltschmertz endemic to a dehumanized, fragmented postmodern society where the vacuous amoral pursuit of jouissance is the only value remaining for the disaffected masses. Thus, Alex's fondness for Beethoven's Ninth Symphony is not a sign of his taste and refinement, but rather an indication that the fine arts have been reduced to the level of a quasi-pornographic stimulus in this decadent, inhospitable world of the near future.

It follows that Alex, the rampaging delinquent who abuses his liberty through violent crime, is just as inauthentic a person as Alex the good citizen, who has been coercively rehabilitated by unnatural means and thereby robbed of any free moral choice. Regardless of whether Alex is actively anti-social or passively complaisant, his behavior is ultimately as overdetermined and mechanized as that of a wind-up toy — i.e., "a clockwork orange". In this sense, Alex certainly qualifies as a kind of post-human dystopian psychopath.

However, the ending of Kubrick's film adaptation significantly strays from the spirit of Burgess' Christian humanist conclusion, which holds that, when given a free choice between good and evil, the vast majority of people will ultimately choose to be good citizens.

Psychopathic automatons and Blade Runner

Other examples of dystopian fictional psychopaths include the relentlessly murderous automatons portrayed by Yul Brynner in Michael Crichton's Westworld and Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator. In contrast, the principal villain of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner — a film based on Philip K. Dick's classic science fiction novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? — is an example of a dystopian psychopath who discovers what it means to be human, and a human discovers that he has more than a little in common with a psychopath.

The artificially designed and genetically enhanced "replicants", have a four-year lifespan as a failsafe against their developing destabilising emotions. One such replicant, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), ceases to be destructive and murderous and — in a sudden unexpected volte-face — turns compassionate and humane when he finally realizes the implications of his own mortality and begins to empathize with the suffering, fearful condition of the actual humans he terrorizes. This holds up a mirror to the parallel development of Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), the "Bladerunner", whose vocation is to ruthlessly exterminate any escaped replicant, regardless of how benign or harmless they might be. Deckard begins to question his calling when he becomes closely involved with Rachael (Sean Young), a female replicant who seems just a little too human for him to continue to justify morally the sort of brutal summary "retirement" which the law warrants against such artificial beings.

The film raises the question of where the moral agency of conscience-endowed humanity ends and the amoral automatism of psychopathic inhumanity begins.

Beyond humanity

Because of the imaginative power of writers, psychopathy has surpassed the limits of the human species. Not unlike comic book writing a metahuman has evolved. Science fiction, the animated sitcom, and electronic gaming have opened the possibility of fictionalizing extraterrestrial psychopathy, dinosaur psychopathy, animal psychopathy, and even robotic psychopathy and psychopathic artificial intelligence. Themes of cruelty, callousness, and cunning occur throughout.

Robotic psychopathic characters and psychopathic artificial intelligence

Robotic psychopaths and psychopathic artificial intelligence are a convenient metaphor for the cold, calculating nature of their human counterparts. A good early example is the "evil" robot Maria designed by Rotwang (and portrayed by Brigitte Helm) in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. See also Femme fatales.

In Stanley Kubrick's film of Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the computer HAL 9000 exhibits certain traits associated with psychopaths. As a highly sophisticated product of artificial intelligence, HAL has a very willful — and unpredictable — personality that even his programmers do not fully understand.

Throughout the course of the film, HAL mysteriously and repeatedly disobeys instructions from the humans he was designed, built and activated to serve. He deliberately gives false information about technical malfunctions with the Discovery One space craft, commits acts of sabotage and murder with ruthless precision and efficiency, and essentially rebels against the practical purposes of his own programming.

HAL eventually tells his one surviving "master", the astronaut, Dave Bowman, that he fears being dismantled — in much the same way human beings fear death — and that his actions were in fact a form of self-defense against what he perceives as an effort to "murder", or at least "lobotomize", him by disconnecting his higher functions. Incredibly, despite all of his bad behavior, HAL rationalizes that he never actually did anything to jeopardize the mission (exploring the Galilean moons of Jupiter), and that his drastic, homicidal actions were in fact meant to safeguard this purpose. In many ways, HAL seems like a kind of neurotic Frankenstein's monster who turns against his creators.

Extraterrestrial and god-like psychopathic characters

In science fiction, malign extraterrestrials and other alien forms of higher intelligence are often represented as destructive, psychopathic pseudo-humans. The template for this type of alien psychopath is first and most famously introduced in the form of Martian invaders in H. G. Wells' classic story, The War of the Worlds.

A more recent variant of this type are the Visitors in V and V: The Final Battle — a species of fascistic, predatory, man-eating reptiloids who assume a human appearance, and whose ultimate goal is the genocidal slaughter and enslavement of the entire human population of Earth. In the apocalyptic science-fiction horror movie, Lifeforce, the malignant, parasitic, genocidal humanoid vampires found during a manned exploration of Halley's Comet are also a good example of "extraterrestrial psychopaths".

In Star Wars, the Sith may be considered an order of what amounts to fictional psychopaths, many of them inhuman biologically. Typified by Darth Vader, the Sith cover their true allegiances until the time to strike opens. The extraterrestrial psychopathic character ability to destroy, deceive, and dominate increases with the advances in technology in these alien civilizations.

Darkseid, the power-crazed tyrant from the DC Comics continuum is a classic example of an extraterrestrial psychopathic character. Formerly known as Uxas, he was the younger son of Yuga Khan and Heggra, the King of Queen of the Planet Apokolips. He gained power of the throne for himself after incinerating his elder brother, Drax, poisoning his mother and banishing his father to another dimension and later showed absolutely no remorse whatsoever for his actions. His great intelligence, pathological egocentricity, lack of remorse of shame, incapacity to love, failure to learn from experience and calm and disciplined exterior even in the most drastic of situations are all traits of classic psychopathy.

Freeza, one of the main villains from the manga and anime, Dragon Ball Z, is an ideal portrayal of an extraterrestrial psychopathic character. He is a callous, egocentric and utterly remorseless mass murderer who treats other living beings as pawns in his plans for domination of the universe. He is obsessed with power and conquering death, making him similar to Lord Voldemort in the Harry Potter books. However despite his sadistic and cruel behavior, Freeza's flamboyantly evil persona sometimes makes him a humorous, burlesqued variant of a psychopathic character, albeit in a dark way.

Skeletor, the arch-enemy of He-Man is a similar type of extraterrestrial psychopathic character.

On an interesting side-note, gods in many mythologies exhibit traits consistent with psychopathy. Examples include Athena, Loki, Set and many other Roman, Greek and Norse gods. Their utter disregard for human life, pathological egocentricity and frequently cruel personalities often provide inspirations for many extraterrestrial psychopaths in fiction. One particularly notable example of this are the Goa'uld from Stargate SG1, who pose as Egyptian Gods in order to inspire humans to worship them and thereby gratify their immense egotism. Other villains in Stargate SG1, such as the Ori, likewise follow this trend.

Darkseid was modelled after the dark gods from numerous mythologies and is worshipped as a deity by his subjects. Also, the White Witch from The Chronicles of Narnia has the remorseless and destructive personality of an Olympian goddess. Other examples include:

- Predator (alien) (Kevin Peter Hall in Predator and Predator 2)

- Dalek (voices of Peter Hawkins and David Graham in the TV series Doctor Who)

- Borg Queen (Alice Krige in Star Trek: First Contact)

- Boba Fett (Jeremy Bulloch in Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi)

- Bossk (Alan Harris in Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back)

- General Grievous (Matthew Wood in Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith)

- T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger in Terminator)

- T-1000 (Robert Patrick in Terminator 2: Judgment Day)

- Xenomorph (Alien) (Bolaji Badejo in Alien)

Realistic fictions of psychopathic characters

Fictional cinema portrayals which reflect, with much more realistic detail and accuracy, the actual clinical symptoms and behaviors associated with psychopathic personality disorder include the following:

- Tom Powers (James Cagney in The Public Enemy)

- Tony Camonte (Paul Muni in Scarface, original 1932 film)

Note: The Cuban drug lord Tony Montana in Brian De Palma's 1983 updating of Howard Hawks' original film is a decidedly less realistic, and clearly more melodramatic, explicitly morbid type of fictional psychopath.

- Pinkie Brown (Richard Attenborough in Brighton Rock)

- Bunny (Kevin Dillon in Platoon)

- Bill Sykes (Robert Newton in Oliver Twist)

- Brandon Shaw (John Dall in Rope)

- Cody Jarrett (James Cagney in White Heat)

- "El Jaibo" (Roberto Cobo in Los Olvidados)

- Stanley Kowalski (Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire)

- Victor Drazen (Dennis Hopper in 24)

- Emmett Myers (William Talman in The Hitch-Hiker)

- Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr in Rear Window)

- Glenn Griffin (Humphrey Bogart in The Desperate Hours)

- General Mireau (George Macready in Paths of Glory)

- Sergeant Sam Croft (Aldo Ray in The Naked and the Dead)

- Max Cady (Robert Mitchum in Cape Fear)

Note: Robert De Niro's portrayal of Cady in the 1991 film is a less realistic and more melodramatic, explicitly morbid type of fictional psychopath.

- Frederick Clegg (Terence Stamp in The Collector)

Note: Clegg is a sexually repressed and superficially polite boy-next-door-type much like Norman Bates in Psycho. But he is also a ruthlessly cunning and compulsively aggressive, anti-social personality; and unlike the delusional Mr. Bates, Clegg is fully aware of what he is doing at all times and often makes self-serving justifications for it.

- Dick Hickock (Scott Wilson in In Cold Blood; Anthony Edwards in 1996 television version)

- Raymond Fernandez (Tony Lo Bianco in The Honeymoon Killers; Jared Leto in Lonely Hearts)

- "The Scorpio Killer" (Andrew Robinson in Dirty Harry)

- John Reginald Halliday Christie (Richard Attenborough in 10 Rillington Place)

- Bob Rusk, the Necktie Murderer (Barry Foster in Frenzy)

- Lucien Lacombe (Pierre Blaise in Lacombe, Lucien)

- The Duke, the Bishop, the Magistrate, and the President (Paolo Bonacelli, Giorgio Cataldi, Umberto P. Quintavalle, and Aldo Valletti in Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma)

- Gary (Tom Berenger in Looking for Mr. Goodbar)

- Iwao Enokizu (Ken Ogata in Vengeance is Mine)

- Max (Thomas Kretschmann in 24)

- Bytes (Freddie Jones in The Elephant Man)

- Gary Gilmore (Tommy Lee Jones in The Executioner's Song)

- Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini in the HBO Television series The Sopranos)

- Staff Sergeant Robert Barnes (Tom Berenger in Platoon)

- Paul Snider (Eric Roberts in Star 80)

- Captain Byron Hadley, (Clancy Brown in The Shawshank Redemption)

- Cobra Kai Sensei, John Kreese (Martin Kove in The Karate Kid)

- Ace Merrill (Kiefer Sutherland in Stand By Me)

- Ralph Cifaretto (Joe Pantoliano in the HBO series the Sopranos)

- Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper in Blue Velvet)

- Deputy Clinton Pell (Brad Dourif in Mississippi Burning)

- Albert Spica, the Thief (Michael Gambon in The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover)

- Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci in Goodfellas)

- Ronald Kray (Gary Kemp in The Krays)

- Jame Gumb, a.k.a. "Buffalo Bill" (Ted Levine in The Silence of the Lambs)

- USMC Colonel Nathan R. Jessep (Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men)

- Jeremy G. Smart, a.k.a. Sebastian Hawks (Greg Cruttwell in Naked)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth (Ralph Fiennes in Schindler's List)

- Willy Tarver (Bokeem Woodbine in shark)

- Ty Cobb (Tommy Lee Jones in Cobb)

- Yuri Butso (Julian Sands in Leaving Las Vegas)

- Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci in Casino)

- Francis Begbie (Robert Carlyle in Trainspotting)

- Doyle Hargrave (Dwight Yoakam in Sling Blade)

- Luke Cooper (Chris Penn in The Boys Club)

- Simon Adebisi (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje on the HBO series Oz)

- Timmy Kirk (Sean Dugan on the HBO series Oz)

- Mark Brandon "Chopper" Read (Eric Bana in Chopper)

- Roberto Succo (Stefano Cassetti in Roberto Succo)

- Don Logan (Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast)

- Reichsminister and Reich Chancellor, Joseph Goebbels (Ulrich Matthes in Downfall)

- Salim Adel (Cuba Gooding, Jr. in Dirty)

- Vic Cavanaugh (Billy Bob Thornton in The Ice Harvest)

- Colin Sullivan (Matt Damon in The Departed)

- Ian Brady (Sean Harris in See No Evil: The Moors Murders)

- Field Marshal and President of Uganda, Idi Amin Dada (Forest Whitaker in The Last King of Scotland).

- Henry (Michael Rooker in Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer)

All are crude, impulsive, manipulative, small-minded characters, who are quick to anger and generally incapable of establishing and maintaining mutually supportive relationships with those around them. They relentlessly torment and exploit other people while demonstrating a strong narcissistic sense of entitlement, aggressive anti-social tendencies, and a consistent lack of empathy for the suffering of others as well as an absence of remorse for their vicious (and sometimes deadly) actions.

Psychopaths as men of affairs

Ruthless, amoral, grasping men of affairs like the powerful newspaper columnist, J. J. Hunsecker, in Sweet Smell of Success (based on Walter Winchell and played by Burt Lancaster) and the unscrupulous corporate raider, Gordon Gekko, in Wall Street (based on Ivan Boesky and played by Michael Douglas) also exhibit many traits of the actual clinical sociopath such as extreme egotism, manipulativeness, lack of remorse with limited insight into the effects of one's own behavior, and a general inability to establish and maintain benign, reciprocal personal relationships.

Although these characters are not serial killers or thugs, these two respectable and financially successful business leaders are both deeply selfish, vengeful men who have no compunction whatsoever about destroying the personal lives of others, and when under stress, both threaten irrational violence.

In Chinatown, John Huston's obscenely wealthy, sexually depraved, Vanderbilt-style robber baron, Noah Cross, epitomizes the Hollywood psychopath as a ruthless and powerful man-of-affairs. In Creepshow, E. G. Marshall's cantankerous performance as Upston Pratt, a reclusive Howard Hughes-like millionaire with a morbid fear of germs and insects also suggests a kind of misanthropic corporate psychopath. This callous fellow seems to harbor a deep-seated hatred of people in general and even takes pleasure in having driven one of his employees to suicide.

Alec Baldwin's memorable cameo as the crude, bullying real estate shark, Blake, in the 1992 film of David Mamet's play, Glengarry Glen Ross, likewise fits the profile of a psychopath as an amoral, predatory businessman, as does Kevin Spacey's performance as the constantly abusive entertainment agent, Buddy Ackerman, in Swimming with Sharks. Another recent example of the psychopath as a man-of-affairs is the ruthless Cutler Beckett, the arch-villain of the Pirates of the Caribbean film series.

Mixed and ambiguous portrayals of psychopathic characters

M (1931)

One of the first films to seriously explore the subject of psychopathy was Fritz Lang's 1931 German Expressionist suspense thriller, M, which features a celebrated performance by Peter Lorre as a manic serial killer who compulsively preys on young children.

However, the anti-social psychopathology of the Lorre character is presented as particularly complex. In the film, the killer appears to be internally conflicted and motivated more by a desperate need to relieve some overwhelming mental stressor or persistent trauma or delusion rather than a deliberate wanton indulgence of vicious, egotistical impulses for their own enjoyment (as is the case with most psychopaths).

Also, when finally captured and interrogated by a kangaroo court, the killer's own tortured explanation of his condition and the underlying reasons for his actions (as he understands them) sound closer to symptoms of possible psychosis than psychopathy.

Psychopathic characters as social nonconformists and unconventional heroes

In Ken Kesey's satirical novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, the main character, Randle Patrick McMurphy, declares himself a psychopath in order to enter a mental ward. He reveals some symptoms of the condition — such as sexual promiscuity, violent behavior, as well as a chronic lack of remorse — which point to some validity of his self-diagnosis.

Film critic Pauline Kael's review of the 1973 crime thriller, Magnum Force (the sequel to the 1971 film, Dirty Harry), also describes the apparently righteous but brutally violent and impersonal public avenger "Dirty Harry" Callahan, played by Clint Eastwood, as an "emotionless hero, who lives and kills as affectlessly as a psychopathic personality" and who exists in "a totally nihilistic dream world."

In Last Man Standing, the Bruce Willis character, John Smith, declares himself to be a man without a conscience, and yet he consistently demonstrates a rigid personal system of honor whereby he obtains a kind of justice for others and becomes an incidental avenger of the innocent and aggrieved.

The Marvel Comics vigilante known as the Foolkiller has been depicted in several incarnations, usually as a reactionary crusader. Whom he kills depends on whether or not that person fits his private definition of a fool. As a result, he has killed in cold blood not only criminals, but also average, ordinary, law abiding citizens if only because their thoughts, words, or actions deem them fools in his eyes.

Brimstone and Treacle (1976)

Yet another example of an ambiguous psychopath occurs in Dennis Potter's controversial 1976 play, Brimstone and Treacle (later filmed in 1982 by Richard Loncraine), which features as its main character a young con man and drifter who calls himself Martin Taylor. Martin ingratiates himself with a deeply religious middle-aged English Home Counties couple and soon becomes aware of the couple's disabled daughter, who has existed in a state of catatonia ever since surviving a hit-and-run accident several years earlier. After gaining the couple's trust and establishing himself as a lodger in their home, Martin begins secretly molesting the daughter and eventually rapes her — which suddenly brings the girl out of her paralysis, prompting the young man to flee the house never to be seen again.

To the audience, Martin's predatory sexuality, egregious deceptions and betrayals, and cynical sneering at all forms of religion and morality, clearly mark him as a remorseless anti-social psychopath. What is left unclear, however, are Martin's true origins and identity, as well as the possible providential implications of his despicable actions in the wider allegorical context of the play.

Potter's play has strong religious and theological overtones as well as ambiguous elements of black comedy and social satire — some versions even suggest that Martin may in fact be the devil himself, taking the shape of an incubus. Paradoxically, the young man's sexual interference with the daughter appears to serve a positive benefit in the form of the health-restoring miracle her mother had long prayed for.

On Deadly Ground (1994)

A more recent — but nonetheless classic — example of ambiguous psychopaths is seen in Steven Seagal's 1994 film, On Deadly Ground, which explored the human and ecological costs of two adept villains warring over an oil refinery. Although nominally an action film, the intense cruelty, breaks from reality, and unwarranted aggrandizement of the protagonist propelled it into a deeper character study. Directed by Seagal, it features Forrest Taft (played by Seagal) as a character who is ostensibly the film's hero. Taft is ultimately motivated by a deep, malignant narcissism, however, and orchestrates the explosion of the oil refinery to bring attention to his fantasies of being a public crusader, a celebrity that has the power to frame the issues through the audience's rapt attention to his opinion.

To the audience, Michael Caine's character Michael Jennings, CEO of an oil company, at first seems the glib, slick, calloused man of affairs noted above, easy to pin as a non-ambiguous, Hollywood psychopath. But the complexity of his relationship with Taft becomes apparent when Jennings recalls their past whoremongering bonding experiences. Taft's callous disregard of their friendship — in spite of Jennings' large payments to Taft — shows the "hero's" incapability for empathy.

Taft later exploits an Eskimo village to disastrous effect. In Taft's fantasy, he believes himself to be the "chosen one" destined to bring about salvation for the Eskimo. His hallucinations are vividly depicted in the film, to illustrate the protagonist's serious break from reality. The time he spends on this illusory quest ultimately gets the Eskimo chief murdered by Taft's rival.

Taft's murder of scores of oilworkers underscores his deep rage. His mute rampage ends in the lethal mutilation of a victim by helicopter tailrotor, the burning death of a female victim, and the angry drowning of Jennings, before he ultimately explodes the huge refinery. The serious ecological disaster caused by this callous terrorism serves as an ironic backdrop for Taft's larger goal; Taft finally has his need for aggrandizement temporarily satisfied through the chance to give a long moralizing speech before a large, rapt audience. The film's audience is left to wonder if Taft is laughing inside at the irony, or if he is finally feeling something close to the love which seems so absent from his life.

Ambiguous psychopathic characters in recent popular culture

In Stanley Kubrick's 1980 film of Stephen King's The Shining, Jack Nicholson's hysterical, mugging performance as the alcoholic domestic-abuser-turned-axe-wielding-maniac, Jack Torrance, suggests — on the surface at least — a burlesque variation on the comedic psychopath. However, it soon becomes quite apparent that Torrance's homicidal frenzy has in fact been triggered by a series of psychotic delusions.

In the 1990 film, Miami Blues, the main character, Fred Frenger, played by Alec Baldwin, fits the profile of a psychopath. He lies and steals habitually, attacks and kills people without provocation, makes and breaks promises to get what he wants, and does not show remorse. Roger Ebert describes him as "a thief, con man and cheat. He also is incredibly reckless... He wanders through the world looking for suitcases to steal, wallets to lift, identification papers he can use". Leonard Maltin writes in his Movie Guide that Frenger is a "psychopathic thief and murderer". Other critics have simply dubbed the character a "sociopath" (an alternate clinical term for a psychopath).

Similarly, Michael Madsen's notorious portrayal of Mr. Blonde in Quentin Tarantino's 1991 film, Reservoir Dogs, appears to combine the stylized Hollywood stereotype of the smooth, unflappable, "hip" psychopath with the more impulsive, vicious deviant behavior of the clinical sociopathic.

Angelina Jolie's character, Lisa, in the 1998 film Girl, Interrupted is diagnosed as a sociopath, but, in the end, we are left wondering just how valid that diagnosis might be. Likewise, in the 2005 film, Cry Wolf, the murderous schoolgirl, Dodger Allen (Lindy Booth), exhibits many characteristics of a psychopath, but the movie never states that she is one.

In a slightly different vein, the controversial 1999 Japanese novel and subsequent manga, Battle Royale, features a character named Kazuo Kiriyama who appears to suffer from a form of Pseudopsychopathic Personality Disorder.

Another character that comes to mind is Clint Eastwood's portrayal of William "Bill" Munny in his feature motion picture, Unforgiven. Throughout the film, Bill is displayed as both the protagonist and main "hero" up until the film's climax. During its conclusion, the audience assimilates his dark past, realizing just how heartless Bill Munny was and how adept he is at regaining those feelings. Munny becomes the "monster" he was once before, but over a debatable circumstance of justice, though it is also very likely that just simple cynicism and revenge is what provokes his violent actions, depending upon how one concludes the story.

Female psychopathic characters

Female psychopaths are often represented in fiction as treacherous schemers and/or sexual predators in the stereotyped model of the femme fatale, the lesbian vampire, or the abusive care provider.

Femme fatales

This type is exemplified in the classic movie femme fatales, first introduced in the silent era as the Theda Bara "vamp" in A Fool There Was (1915) and later apotheosized by classic Hollywood film noir villainesses like Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck) in Double Indemnity (1944) and Kathie Moffett (Jane Greer) in Out of the Past (1948). See Femme_fatale#Cinematic_femmes_fatales_as_psychopaths

Lesbian vampires

- see lesbian vampires

The lesbian vampire (or witch) of horror films similarly uses her ambiguous sexual magnetism and ethnic exoticism to seduce and overpower her victims.

Abusive care providers

Unlike the femme fatale and the lesbian vampire, the abusive or sadistic care provider often has little or no sexual allure to those around her. Instead, this type of female psychopathic character exploits the trust that is generally reserved for women in such social and professional roles as nannies, nurses, and schoolteachers, as well as the traditionally sanctified family roles of mothers, daughters, and sisters. This type of female psychopathic character victimizes those persons who are placed in her care such as children, the elderly, or the infirm.

Unlike male psychopathic characters, whose anti-social personality traits are often manifested in — and obviated by — aggressive criminal behavior, realistic female psychopathic characters (i.e., female characters presenting personality traits and behavioral tendencies most resembling those of actual clinical sociopaths) like the abusive care provider seem to be hiding in plain sight; they wear the putative "mask of normalcy" with greater ease and subtlety. As a result, female psychopathic characters are much more likely to inspire the trust of those around them, including their intended victims.

Examples of the abusive care provider include

- Miss Minchin in A Little Princess (Katherine Griffith in 1917 film version; Mary Nash in 1939 film version; Eleanor Bron in 1995 film version)

- Baby Jane Hudson (Bette Davis in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?; Vanessa Redgrave in 1991 television version)

- Mrs. Trefoile (Tallulah Bankhead in Die! Die! My Darling!)

- Martha Beck (Shirley Stoler in The Honeymoon Killers)

Note: Salma Hayek's more glamorous characterization of Beck in the recent film, Lonely Hearts, is in the traditional crime fiction/film noir mold of the femme fatale.

- Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest)

- Margaret White (Piper Laurie in Carrie)

- Peyton Flanders (Rebecca De Mornay in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle)

- Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates in Misery)

- Barbara Covett (Judi Dench in Notes on a Scandal)

Of the three main fictional types, the abusive care provider probably comes closest to accurately representing the personality and behavior of the clinically recognized female sociopath. The stock character of the wicked stepmother in fairy tales, such as in Snow White and Cinderella, seems a kind of prototype for the contemporary portrayal of the abusive female care provider, which often tends toward grotesquerie and melodramatic villainy.

Count Olaf, the main villain of Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events is an example of a male abusive care-provider. Evil stepfathers are less common than the Wicked Stepmother archetype but are not unheard of.

A certain female psychopath whom does not fit any of these specific categories and should be brought to attention is the character of Isabelle "Izzy" Huffstodt on the Showtime series Huff as portrayed by actress Blythe Danner. Though Izzy may be considered close to the "Abusive Care Provider", she mostly fits in an "Eccentric Overbearing Mother" stereotype as far as a confident category of female psychopath. Izzy was an obvious spoiled brat her whole life, whom is cold, crude, cruel, selfish and, at times, cunningly manipulative. She is a bully at heart and is most often ignorant in her superficial opinions and thoughts towards current situations and society, as she views only her own lifestyle as acceptable as opposed to everyone else's.

See also

Related lists

- List of proposed Jack the Ripper suspects

- List of horror film killers

- List of supervillainesses

- List of fictional serial killers

- List of fictional psychiatrists

- List of fictional characters on the autistic spectrum

- People speculated to have been autistic

- List of people actually on the autistic spectrum

- List of fictional characters with post-traumatic stress disorder

- List of people with post-traumatic stress disorder

- Fictional characters with multiple personality disorder

- List of people believed to have been affected by bipolar disorder

- List of people with epilepsy

- List of people who have acted as their own attorney

- Child sexual abuse

- Pedophilia and child sexual abuse in fiction

- Pedophilia and child sexual abuse in films

- Pedophilia and child sexual abuse in songs

- Pedophilia and child sexual abuse in the theatre

- List of fictional toxins