Flâneur

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"Around 1840 it was briefly fashionable to take turtles for a walk in the arcades. The flaneurs liked to have the turtles set the pace for them."--The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire (1938) by Walter Benjamin "And so away he goes, hurrying, searching. But searching for what? Be very sure that this man, such as I have depicted him—this solitary, gifted with an active imagination, ceaselessly journeying across the great human desert—has an aim loftier than that of a mere flaneur, an aim more general, something other than the fugitive pleasure of circumstance. He is looking for that quality which you must allow me to call 'modernity'; for I know of no better word to express the idea I have in mind." --The Painter of Modern Life (1863) by Charles Baudelaire, tr. Mayne |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

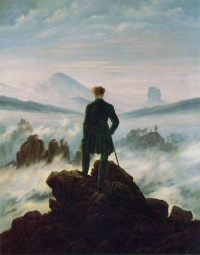

The term "Flâneur" comes from the French verb flâner, which means "to stroll". A flâneur is thus a person who walks the city in order to experience it. Because of the term's usage and theorization by Charles Baudelaire and numerous thinkers in economic, cultural, literary and historical fields, the idea of the flâneur has accumulated significant meaning as a referent for understanding urban phenomena and modernity. The word has no exact equivalent in English. The concept of the flâneur is important in the work of Walter Benjamin, in academic discussions of modernity, architecture and urban planning. Flânerie is connected to such concepts as psychogeography, wandering and la dérive. Generally overlooked in contemporary discussions of the flâneur is the original dandy-ish "m'as-tu-vu?" character of flânerie (Gérard de Nerval was known in his own day for parading a lobster on a pale blue ribbon through Paris).

Overview

Around 1850, Baudelaire began asserting that traditional art was inadequate for the new dynamic complications of modern life. Social and economic changes brought by industrialization demanded that the artist immerse himself in the metropolis and become, in Baudelaire's phrase, 'a botanist of the sidewalk', an analytical connoisseur of the urban fabric. Because he coined the word about Parisians, the 'flâneur' (the one who strolls) and the 'flânerie' (the stroll) are associated with Paris and the kind of pedestrian environment which accommodates leisurely exploration.The Flâneur is typically well aware of their slow, leisurely behaviour and had been known to exemplify this state of being by walking turtles on leashes down the streets of Paris .

Walter Benjamin adopted this concept of the urban observer both as an analytical tool and as a lifestyle. From his Marxist standpoint Benjamin describes the flâneur as a product of modern life and the Industrial Revolution, unprecedented in history and definitely of a certain social class, parallel to the advent of the tourist. His flâneur is an uninvolved but highly perceptive bourgeois dilettante. Benjamin became his own prime example, gathering his social and aesthetic observations from long walks through Paris. Even the title of his unfinished Arcades Project comes from his affection for covered shopping streets.

Context

While Baudelaire characterized the flâneur as a "gentleman stroller of city streets", he saw the Flâneur as having a key role in understanding, participating in and portraying the city. A flâneur thus both played a role in city life and (in theory) remained a detached observer. This stance, simultaneously part of and apart from, combines sociological, anthropological, literary and historical notions of the relationship between the individual and the crowd. After the 1848 Revolution, after which the empire was reestablished with clearly bourgeois pretentions to "order" and "morals", Baudelaire began asserting that traditional art was inadequate for the new dynamic complications of modern life. Social and economic changes brought by industrialization demanded that the artist immerse himself in the metropolis and become, in Baudelaire's phrase, "a botanist of the sidewalk". David Harvey asserts that "Baudelaire would be torn the rest of his life between the stances of flaneur and dandy, a disengaged and cynical voyeur on the one hand, and man of the people who enters into the life of his subjects with passion on the other" (Paris: Capital of Modernity 14).

Because he coined the word to refer to Parisians, the "flâneur" (the one who strolls) and "flânerie" (the act of strolling) are associated with Paris. However, the critical stance of flânerie is now applied more generally to any kind of pedestrian environment that accommodates leisurely exploration of city streets, in particular commercial avenues where inhabitants of different classes mix. Indeed, diverse texts such as Baudrillard's America, or Jack Kerouac's On the Road demonstrate the concept's impact and flexible usage.

The observer-participant dialectic is evidenced in part by the Dandy culture. Highly self-aware, and to a certain degree flamboyant and theatrical, dandies of the mid-nineteenth century created scenes through outrageous acts like walking turtles on leashes down the streets of Paris. Such acts exemplify a flâneur's active participation in and fascination with street life while displaying a critical attitude towards the uniformity, speed and anonymity of modern life in the city.

The concept of the flâneur is important in academic discussions of the phenomenon of modernity. While Baudelaire's aesthetic and critical visions helped open-up the modern city as a space for investigation, theorists such as Georg Simmel began to codify the urban experience in more sociological and psychological terms. In his essay The Metropolis and Mental Life, Simmel theorizes that the complexities of the modern city create new social bonds and new attitudes towards others. The modern city was transforming humans, giving them a new relationship to time and space, inculcating in them a "blasé attitude," and altering fundamental notions of freedom and being:

The deepest problems of modern life derive from the claim of the individual to preserve the autonomy and individuality of his existence in the face of overwhelming social forces, of historical heritage, of external culture, and of the technique of life. The fight with nature which primitive man has to wage for his bodily existence attains in this modern form its latest transformation. The eighteenth century called upon man to free himself of all the historical bonds in the state and in religion, in morals and in economics. Man's nature, originally good and common to all, should develop unhampered. In addition to more liberty, the nineteenth century demanded the functional specialization of man and his work; this specialization makes one individual incomparable to another, and each of them indispensable to the highest possible extent. However, this specialization makes each man the more directly dependent upon the supplementary activities of all others. Nietzsche sees the full development of the individual conditioned by the most ruthless struggle of individuals; socialism believes in the suppression of all competition for the same reason. Be that as it may, in all these positions the same basic motive is at work: the person resists to being leveled down and worn out by a social-technological mechanism. An inquiry into the inner meaning of specifically modern life and its products, into the soul of the cultural body, so to speak, must seek to solve the equation which structures like the metropolis set up between the individual and the super-individual contents of life.(The Metropolis and Mental Life)

The concept of the flâneur has also become meaningful in architecture and urban planning. Walter Benjamin adopted the concept of the urban observer both as an analytical tool and as a lifestyle. From his Marxist standpoint, Benjamin describes the flâneur as a product of modern life and the Industrial Revolution, without precedent, parallel to the advent of the tourist. His flâneur is an uninvolved but highly perceptive bourgeois dilettante. Benjamin became his own prime example, making social and aesthetic observations during long walks through Paris. Even the title of his unfinished Arcades Project comes from his affection for covered shopping streets. In 1917, the Swiss writer Robert Walser published a short story called "Der Spaziergang", or "The Walk". It is a masterpiece of flâneur literature.

In the context of modern-day architecture and urban planning, designing for flâneurs is one way to approach issues of the psychological aspects of the built environment. Architect Jon Jerde, for instance, designed his Horton Plaza and Universal CityWalk projects around the idea of providing surprises, distractions, and sequences of events for pedestrians.

See also