History of Materialism and Critique of Its Present Importance

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

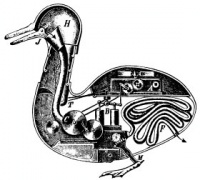

Illustration:The Canard Digérateur, or Digesting Duck, an automaton in the form of duck, created by Jacques de Vaucanson in 1739

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Geschichte des Materialismus und Kritik seiner Bedeutung in der Gegenwart ("History of Materialism and Critique of its Present Importance") is a philosophical work by Friedrich Albert Lange on materialism. It was originally written in German and published in October 1865 (although the year of publication was given as 1866). Lange vastly extended the second edition published in two volumes in 1873–75. A three-volume English translation of the opus was published 1877–81.

Adopting the Kantian standpoint that we can know nothing but phenomena, Lange maintains that neither materialism nor any other metaphysical system has a valid claim to ultimate truth. For empirical phenomenal knowledge, however, which is all that man can look for, materialism with its exact scientific methods has done most valuable service. Ideal metaphysics, though they fail of the inner truth of things, have a value as the embodiment of high aspirations, in the same way as poetry and religion. Lange replaced the transcendental subject of Kantism by the organism, although he considered that this substitution validated all the more Kant's philosophy that the subject apprehended the world through the categories of understanding.

Lange suggests that the methods for real science were present in Democritus's atomistic materialism. However, atomistic materialism implies that the soul, like the body, is fated to be snuffed out: such a view made Democritus quite unattractive to virtually all world religions so Democritus was ignored and marginalized by the history of philosophy, in spite of being one of the greatest thinkers of the ancient Greek world.

Lange mentions Max Stirner's book The Ego and Its Own as "the extremest that we know anywhere". ("Stirner went so far in his notorious work, Der Einzige und Sein Eigenthum (1845), as to reject all moral ideas. Everything that in any way, whether it be external force, belief, or mere idea, places itself above the individual and his caprice, Stirner rejects as a hateful limitation of himself. What a pity that to this book — the extremest that we know anywhere — a second positive part was not added. It would have been easier than in the case of Schelling's philosophy; for out of the unlimited Ego I can again beget every kind of Idealism as my will and my idea. Stirner lays so much stress upon the will, in fact, that it appears as the root force of human nature. It may remind us of Schopenhauer. Thus there are two sides to everything." — History of Materialism, Second Book, First Section, Chapter II, "Philosophical Materialism since Kant") He also mentioned Blanqui's L'Eternité par les astres, which discussed the thesis of an Eternal Return.

Lange's work exerted a profound influence on Friedrich Nietzsche, who aimed at radicalizing Lange's viewpoint beyond Kant. At one time Nietzsche planned to write a dissertation on the notion of organism in Kant's philosophy (letter to Paul Deussen [1]). He also envisioned sending a work on Democritus, a major focus of Lange, to Deussen.

References

- Friedrich Nietzsche's letter to Gersdorff, September 1866

Full text of volume 1[2]

VOL. I.

BOSTON: JAMES R. OSGOOD AND COMPANY,

{Late Ticknor <£ Fields, and Fields, Osgood, & Go. ) 1877.

npz

-3

l

TO MY FATHER

(HJjfs JEransIatt0Ti is

AFFECTION A TEL Y DEDICA TED.

E. C. T.

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE.

The " History of Materialism " was hailed, upon its original publication in Germany, as a work likely to excite con- siderable interest. In this country, Professor Huxley suggested, in the " Lay Sermons, Lectures, and Addresses " (published in 1870), that a translation of the book would be "a great service to philosophy in England." Soon afterwards there was published a second — thoroughly re- modelled and re-written — edition of the work. And then, in the autumn of 1874, attention was again specially directed to it by Professor TyndaLTs acknowledgment of his indebtedness " to the spirit and to the letter " of the work in his memorable address as President of the British Association at Belfast.

It was shortly after this that, seeing with regret that the book had so long awaited a translator, I ventured to apply to the author for his authority to undertake the task. The causes that have delayed its completion, since they are personal to myself, it would be an impertinence to trouble the reader with. The only one that is not so, is to be deplored on other grounds besides that of mere delay. The lamented death of the author, in November 1875, deprived me of the hoped-for opportunity of sub- mitting my rendering to his friendly criticism.

The impatience expressed in many quarters has decided us to defer publication no longer; and accordingly the

viii TR A NSLA TOR'S PRE FA CE.

reader lias now before him the first instalment, to be speedily followed by two other volumes, which will com- plete the work. The division into three volumes instead of two — which in some respects might have been prefer- able — has been dictated by practical considerations.

The difficulties attending the translation of a philoso- phical German work into English are notorious/ It would be absurd to suppose that I have always succeeded in meeting or eluding these difficulties; but I have endea- voured everywhere to translate as literally as was consis- tent with English idiom.

It may serve also to explain possible obscurities to remember that the book is written with continual refer- ence to the problems and questions under discussion in Germany, and to the forms of speculation current there. It has been treated, indeed, by Von Hartmann as a polemic, 'eine durch geschichtliche Studien angeschwollene Ten- denzschrift.' 1 And as an assertion of the Materialistic standpoint against the philosophy of mere 'Notions' (' intuitionless conceptions/ in Coleridge's phrase), and of the Kantian or Neo-Kantian standpoint against both, no doubt it is a polemic ; but it is, at the same time, raised far above the level of ordinary controversial writing by its thoroughness, its comprehensiveness, and its impartiality.

E. C. T.

2 South Square, Gray's Ink.

1 See Eduard von Hartmann : Neukantianismus, Schopenhauerianismus und Hegelianismus in ihrer Stellung zu den philosophischen Aufgaben der Gegenwart. Berlin, 1877.

FREDERICK ALBERT LANGE BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES.

Frederick Albert Lakge was born at Wald near Solingen, in the district of Düsseldorf, on the 28th of September 1828. He was the son of the well-known Bible Com- mentator, Dr. J. P. Lange, now Professor in Bonn, who has also shown himself possessed of special capacities by rising from the position of a carter and labourer to be one of the leading Evangelical theologians of Europe.

The boy's early life was spent in Duisburg ; but at the age of twelve, his father having received a call as Professor to Zürich, Switzerland became his second • Eatherland,' and until the last he retained a strong love for the Be- public and a keen interest in its politics. Already in his earlier years this interest must have been excited, for in that stirring period political passions extended even to the boys at school.

In 1848, having already attended the University of Zürich for two sessions, he followed the German custom of migrating from university to university, and went to Bonn to attend lectures on philology. His journey had to be made through a country shaken by the storms of that revolutionary period ; and he wore for his protection while travelling a cockade of black gold and red. This he, with the patriot Arndt, was one of the last in Bonn to lay aside. All the struggles and activities of the time he followed with interest and enthusiasm. In a letter written in May 1 849, he asks, " Should it not be clear to every reason- able man that civilised Europe must enter into one great

x BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES.

political community ? " Unfortunately, twenty- eight years have done little to bring us nearer to this ideal. Another of his aspirations, expressed somewhat later, was destined to be realised. Germania was to wake up, like the hero- maiden in Schiller's poem, and cry, " Give me my helm ! "

Having taken his degree of Doctor, he became an assistant-master in the ' Gymnasium,' or grammar-school, at Cologne ; and in the following year he married.

But in 1855 he returned to Bonn as ' Privat-docent ' of philosophy, lecturing on the History and Theory of Edu- cation, on the Schools of the Sixteenth Century, on Psychology, on Moral Statistics, and finally, in the summer of 1857, upon the History of Materialism. At the same time he was studying natural science, attending the lectures of Helmholtz upon physiology, and profiting by intimate intercourse with Frederick Ueberweg, the author of the well-known " System of Logic," and the " History of Philosophy."

In 1858, however, he was fain to take a mastership once more, this time at the Gymnasium at Duisburg ; and there he continued until political considerations caused him to resign in 1861. He had now devoted himself to social and economic questions and to political agitation ; and, amongst numerous other offices, filled the position of secretary to the Chamber of Commerce at Duisburg. In this post he gave evidence of a genius for finance which astonished and delighted the merchants and manufacturers of Duisburg. He was still, moreover, steadily working at his " History of Materialism," and was at the time deliver- ing privately courses of lectures on the History of Modern Philosophy. Prom 1 862 until 1 S66 he was one of the editors of the daily newspaper the " Rhein- und Buhrzeitung," and maintained the principles of freedom and progress against the onslaught of reactionary government. His occupations were still further multiplied by his becoming a partner in a publishing and printing business, in which he undertook the direction of the printing establishment.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES. xi

He was anxious for the spread of information amongst the people. Among the various works which he published at this period were his "Arbeiterfrage" (Labour Ques- tion), 1865, third edition 1874; and "John Stuart Mill's Ansichten über die Sociale Frage und die angebliche Umwälzung der Socialwissenschaft durch Carey," 1866 (Mill's views on the social question and the asserted revolution worked in social science by Carey). He founded also a newspaper to represent the interests of labour in the Ehenish and Westphalian provinces, but the attempt was continued for nine months only.

His own position was meanwhile becoming very dim- cult. His bold and independent treatment of the social question, which was then in the full tide of the agitation led by Ferdinand Lassalle, caused some coldness between Lange and his political friends. At the same time he was harassed by the press prosecutions which German Govern- ments seem unable to avoid, and which the German people still continue to endure. Under these circumstances, he accepted overtures of partnership made to him by an old schoolfellow, who was proprietor of the well-known demo- cratic newspaper, the " Landbote " of Winterthur, then, as now, a paper of great influence. To Winterthur, accord- ingly, he removed with his wife and family in November 1866; and he was speedily engaged to fill as many muni- cipal and public offices as he had already held at Duisburg.

But the love of teaching, which had always been strong within him, led him to join the University of Zürich as a ' Privat-docent,' although he continued to live in Winter- thur, until, in 1870, he was called to Zürich as Professor of Philosophy. For two years he worked zealously here, and declined a call to Königsberg. But much as he loved Switzerland, yet Germany was his true home, and a feel- ing of home-sickness (as he says) came over him when, in 1872, he was again invited by the Minister Falk to become Professor at Marburg. He accepted the invitation, and once more removed.

xii BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES.

His work at Marburg was destined to be of short dura- tion. The disease which ultimately proved fatal had some time before declared itself. He had undergone a serious operation, though with little prospect of advantage, at Tübingen, from which place he wrote to his wife : —

u Yesterday, in the Botanical Garden, I read ' Die Künstler ' once more. I could not help applying a little to myself the splendid lines which have always been favourites with me —

' At peace with Fate, serenely goes his race — Here guides the Muse, and there supports the Grace ; The stern Necessity, to others dim With Mght and Terror, wears no frown for him : Calm and serene, he fronts the threatened dart, Invites the gentle bow, and bares the fearless heart.' 1

" Can one express the Christian idea of resignation more beautifully or philosophically ? And yet with such true poetry ! "

For two years, however, he laboured with great energy and eminent success, lecturing before large classes upon various subjects connected with philosophy. These em- braced logic and psychology, as a matter of course, but they were by no means limited to these. In one session, for instance, he lectured on the History of Modern Educa- tion, on the Theory of Voting, and on Schiller's Philoso- phical Poems.

It has been already mentioned that the " History of Ma- terialism" had originally formed the subject of a course of lectures at the University of Bonn. By the side of such a list, indeed, the lecture-lists of the professors at our great English universities look very jejune and meagre. And it will be long, perhaps, before an Oxford professor lectures

1 I have used the translation of Lord Lytton, Knebsworth edition of his " Translations from Schiller," p. 220. The original lines are — " Mit dem Geschick in hoher Einigkeit Gelassen hingestützt auf Grazien und Musen, Empfängt er das Geschoss, das ihn bedräut, Mit freundlich dargebotenem Busen, Vom sanften Bogen der Notwendigkeit."

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES. xiii

upon any subject so real as the ' Present Significance of Materialism.' But then, as we all know, our English uni- versities are the proper homes of dead languages, and not of living ones; of extinct systems, and not of living, breathing thought. At Oxford, philosophy begins with Plato and ends with Aristotle ; unless, perhaps, as some concession to two thousand years, we throw in a few aphorisms of Bacon, or a ' strayed scholastic ' like Mr. Mill. Meanwhile his disease continued its painful progress; but, undismayed by the approach of death, he busied him- self, in addition to his professorial duties, with the prepara- tion of the second edition of the " History of Materialism." The preface to the first volume of this substantially new work is dated June 1 873 ; to the second, the ' end of January 1875/ After February of this same year, 1875, he was unable to leave the house again. Until three weeks before his death, and while his voice could scarcely rise above a whisper, he continued to work at his " Logical Studies," which have since been published. He died on the 21st of November.

With him, in the words of one of his old colleagues at Duisburg, there went to the grave " a light of science, a standard-bearer of freedom and progress, and a character of spotless purity."

Lange's restless activity and many-sidedness may be readily seen from the facts here put together. The distin- guishing features of his mind and character are sufficiently illustrated in his great work, now presented to the reader. But two points that may be specially mentioned were, his intense belief in the ' reality of ideals ; ' and the way in which he connects the theories of science with ethical ideas. His heart beat for the lot of the masses, and he felt that the question of labour would be the great problem of the coming time, as it was the question that decided the fall of the ancient world. The core of this problem he believed to be ' the struggle against the struggle for existence,' which is identified with man's spiritual des-

xiv BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES.

tiny. And so we can understand the anxiety with which he looked forward to the great revolution which, in common with many thoughtful men, he believed to be impending upon modern society. But all that he could do to warn his fellow-men of the 'rocks' that were ' ahead/ and of the way in which they might be avoided, he did, not discouraged although he were little heeded. In his own words : " Never, indeed, will our efforts be wholly in vain. The truth, though too late, yet comes soon enough ; for mankind will not die just yet. Fortu- nate natures hit the right moment; but never has the thoughtful observer the right to be silent, merely because he knows that for the present there are but few who listen to him."

AUTHOR'S PREFACE TO THE SECOND [AND LATER] EDITIONS.

The changed form in which the "History of Materialism" appears in this second edition is partly a necessary con- sequence of the original plan of the book, but partly also a result of the reception it has met with.

As I incidentally explained in the first edition, my intention was rather to exercise an immediate influence ; and I should have been quite content if my book had, in the course of five years, been again forgotten. Instead of this, however, and despite a number of very friendly re- views, it required almost five years for it to become thoroughly known, and it was never in greater demand than at the moment when it went out of print, and, as I felt, was already in many parts out of date. This was especially so with regard to the second portion of the work, which will receive at least as thorough a revision and remodelling as this present volume. The Books, the Persons, and the Special Questions around which turns the strife of opinions are partially changed. In par- ticular, the rapid progress of the natural sciences required an entire renewal of the matter of some sections, even although the line of thought and the results might remain essentially unaltered.

The first edition, indeed, was the fruit of the labours of many years, but it was in point of form almost extem- porised. Many defects incident to this mode of origin have been removed ; but, on the other hand, some of the

xvi -A UTHOR 'S PRE FA CE.

merits of the first edition may have at the same time disappeared. I wished, on the one hand, to do justice to the higher standard which its readers, contrary to my original intention, have applied to the book; while, on the other, the original character of the work could not be wholly destroyed. I am very far then from claiming for the earlier portion, in its new form, the character of a normal historical monograph. I could not, and indeed I did not, wish to discard the predominant didactic and expository tone, that from the outset labours for and pre- pares the way for the final results of the Second Book, and sacrifices to this effort the placid evenness of a purely objective treatment. But as I everywhere appealed to the sources, and gave abundant vouchers in the notes, 1 1 oped in this way to supply to a great extent the want of a pro- per monograph, without prejudice to the essential purpose of the book. This purpose consists now, as before, in the exposition of principles, and I am not over-eager to justify myself if some slight objection is therefore made to the appropriateness of my title. This has now its historical justification, at all events, and may remain. , The two parts, however, form to me now, as before, an inseparable whole ; but my right expires as soon as I lay down the pen, and I must be content if all my readers, even those who can use for their purposes only particular portions of the whole, will give due weight to the consideration of the difficulty of my task.

A. LANGE. Makeükg, June 1873.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

.first Booft.

HISTORY OF MATERIALISM UNTIL KANT.

First Section. — Materialism in Antiquity. CHAPTER I.

The Early Atomists, especially Demokritos . Pp. 1-36

Materialism one of the earliest attempts at a philosophical theory of the world ; conflict between philosophy and religion, 3. Evidence of this conflict in Ancient Greece, 5. Intercourse with the East ; com- merce; rise of philosophy, 8. Influence of mathematics and the study of nature, 9. The prevalence of deduction, n. Strict carry- ing out of Materialism by Atomism, 13. Demokritos, his life and character, 15. His doctrines, 18. Eternity of matter, 19. Neces- sity, 20. The atoms and void space, 22. Formations of worlds, 24. Qualities of things, and of the atoms, 27. The soul, 28. Ethic, 31. Empedokles and the origin of adaptations, 32.

CHAPTER II.

The Sensationalism op the Sophists, and Aristippos's Ethical Materialism ..... Pp. 37-51

Sensationalism and Materialism, 37. The Sophists, especially Prota- goras, 38. Aristippos, 44. Eelation of theoretical to practical Materialism, 46. Dissolution of Hellenic civilisation under the in- fluence of Materialism and Sensationalism, 48.

CHAPTER III.

The Reaction against Materialism and Sensationalism : Sokrates, Plato, Aristotle . . Pp. 52-92

Undoubted retrogression and doubtful progress of the Athenian school as compared with Materialism, 52. The step from the particular to

b

xviii TABLE OF CONTENTS.

the universal ; preparation for it by the Sophists, 55. The causes of progress by antitheses, and of the combination of great advances with reactionary elements, 57. State of things in Athens, 58. Sokrates as a religious reformer, 60. Contents and tendency of his philosophy, 63. Plato, his intellectual tendency and development, 71. His conception of the universal, 75. The 'ideas' and the ' myth ' in the service of speculation, 77. Aristotle ; not an Empi- ricist, but a system-maker, 80. His teleology, 83. His doctrine of substance ; name and essence, 85. Method, 88. Criticism of the Aristotelian philosophy, 90.

CHAPTER IV. Materialism in Greece and Rome after Aristotle : Epi-

KUROS ..... Pp. 93-I25

Intermittent influence of Greek Materialism, 93. Character of post- Aristotelian Materialism ; ethical aim predominant, 95. The ' Ma- terialism' of the Stoics, 96. Epikuros, his life and character, 98. His reverence of the gods, 100. Deliverance from superstition and the fear of death, 101. Doctrine of pleasure, 102. Physics, 103. Logic, and the theory of knowledge, 107. Epikuros as author, in. Tran- sition from the reign of philosophy to the predominance of the posi- tive sciences ; Alexandria, 112. Share of Materialism in the achieve- ments of Greek scientific inquiry, 120.

CHAPTER "V. The Didactic Poem of Lucretius upon Nature Pp. 126-158

Home and Materialism, 126. Lucretius; his character and tendency, 129. Contents of the First Book ; religion as source of all evil, 132. Nothing can come from nothing, and nothing can be annihilated, 133- Void space and atoms, 134. Praise of Empedokles ; the in- finity of the universe, 136. Idea of gravity, 137. Adaptations as persistent case among all possible combinations, 138. Contents of the Second Book ; the atoms and their motion, 140. Origin of sen- sation ; the infinite number of originating and perishing worlds, 143. Contents of the Third Book ; the soul, 145. The vain fear of death, 147. Contents of the Fourth Book ; the special anthropology, 149. Contents of the Fifth Book ; cosmogony, 149. The method of pos- sibilities in the explanation of nature, 150. Development of man- kind ; origin of speech, of the arts, of political communities, 152. Religion, 155. Contents of the Sixth Book; meteoric phenomena ; diseases ; Averniau spots, 155. Explanation of magnetic attraction, T-S7-

TABLE OF CONTENTS. xix

Second Section. — The Period of Transition. CHAPTER I.

The Monotheistic Religions in their Relation to Mater- ialism ...... Pp. 161-186

Decay of the ancient civilisation, 161. Influence of slavery ; of the mix- ture of religions ; of half -culture, 164. Infidelity and superstition ; Materialism of life ; luxuriance of vice and of religions, 165. Chris- tianity, 169. Common features of the Monotheistic religions, 172. The Mosaic doctrine of creation, 174. Purely spiritual conception of God, 175. Strong opposition of Christianity to Materialism, 176. More favourable attitude of Mohammedanism ; Averroism ; services of the Arabians to natural science ; Freethinking and toleration, 277. Influence of Monotheism on the aesthetic appreciation of nature, 184.

CHAPTER II.

Scholasticism, and the Predominance op the Aristotelian Notions oe Matter and Form . . Pp. 187-214

The Aristotelian confusion of name and thing as basis of the Scholastic philosophy, 187. The Platonic conception of genus and species, 190. Fundamental ideas of the Aristotelian metaphysic, 192. Criticism of Aristotle's notion of Potentiality, 194. Criticism of the notion of Substance, 198. Matter, 200. Modern modifications of this notion, 201. Influence of the Aristotelian notions on the doctrine of the soul, 202. The question of Universals ; Nominalists and Eealists, 207. Influence of Averroism ; of the Byzantine logic, 210. Nomi- nalism as forerunner of Empiricism, 213.

CHAPTER III.

The Return of Materialistic Theories with the Regenera- tion op the Sciences .... Pp. 215-249

Scholasticism as a bond of union in the civilisation of Europe, 215. The Renascence movement ends with the reform of philosophy, 216. The doctrine of twofold truth, 218. Averroism in Padua, 219. Petrus Pomponatius, 220. Nicolaus de Autricuria, 225. Laurentius Valla, 226. Melanchthon and various psychologists of the Reformation period, 227. Copernicus, 229. Giordano Bruno, 232. Bacon of Verulam, 236. Descartes, 241. The soul with Bacon and Descartes, 244. Influence of animal psychology, 245. Descartes' system, and his real opinions, 246.

xx TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Third Section.— Seventeenth Century Materialism.

CHAPTER I.

Gassendi . ■ . . . . Pp. 253-269

Gassendi as restorer of Epikureanism, 253. Choice of this system with reference to the needs of the time, especially in respect of scientific inquiry, 254. Compromise with theology, 257. Gassendi's youth ; the ' Exercitationes Paradoxicae,' 258. His character, 259. Polemic against Descartes, 260. His doctrines, 263. His death ; his import- ance for the reform of physics, and the philosophy of nature, 269.

CHAPTER II.

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury . . Pp. 270-290

Hobbes's development, 270. Labours and experiences during his stay in Prance, 272. Definition of philosophy, 274. Method; connection with Descartes, not with Bacon ; his recognition of great modern dis- coveries, 276. Attack upon theology, 279. Hobbes's political sys- tem, 280. Definition of religion, 283. Miracles, 284. Physical principles, 285. Relativity, 287. Theory of sensation, 288. The universe and the corporeality of God, 290.

CHAPTER III.

The Later Workings of Materialism in England Pp. 291-330 Connection between the Materialism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, 291. Circumstances in England favouring the spread of Materialism, 292. The union of scientific Materialism with religious faith ; Boyle and Newton, 298. Boyle ; his life and character, 300. His predilection for experiment, 302. Adheres to the mechanical theory of the universe, 303. Newton's life and character, 306. Con- siderations on the true nature of Newton's discovery ; he shared the general belief in a physical cause of gravity, 308. The idea that this hypothetical agent determines also the motion of the heavenly bodies lay very near, and the way was already prepared for it, 309. The reference of the combined influence to the individual particles was a consequence of Atomism, 311. The supposition of an impon- derable matter, producing gravitation by its impulse, was already prepared for, through Hobbes's relative treatment of the notion of atoms, 311. Newton declares most distinctly against the now pre- vailing notion of his doctrine, 312. But he separates the physical from the mathematical side of the question, 314. From the triumph of purely mathematical achievements arose a new physics, 315. In- fluence of the political activities of the age on the consequences of the systems, 317. John Locke, his life and intellectual development, 318. His " Essay concerning Human Understanding," 320. Other writings, 323. John Toland, his idea of a philosophical cultus, 324. The treatise on "Motion Essential to Matter," 326.

JFtrSt 38ook,

HISTORY OF MATERIALISM UNTIL KANT.

VOL. I.

FIRST SECTION.

MATERIALISM IN ANTIQUITY.

CHAPTEE I.

THE EARLY ATOMISTS — ESPECIALLY DEMOKRITOS.

Materialism is as old as philosophy, but not older. The physical conception of nature which dominates the earliest periods of the history of thought remains ever entangled in the contradictions of Dualism and the fantasies of per- sonification. The first attempts to escape from these con- tradictions, to conceive the world as a unity, and to rise above the vulgar errors of the senses, lead directly into the sphere of philosophy, and amongst these first attempts Materialism has its place. 1

With the beginning, however, of consecutive thinking there arises also a struggle against the traditional assump- tions of religion. Eeligion has its roots in the earliest

1 My first sentence, which has been rience, of sound common sense, and of sometimes misunderstood, is directed, the physical sciences. It might, per- on the one hand, against the despisers haps, have been more simply main- of Materialism, who find in this view tained that the first attempt at a of the universe an absolute eontradic- philosophy at all amongst the Ionic tion of all philosophical thought, and physicists was Materialism ; but the deny it the possession of any scientific consideration of a long period of de- importance ; and. on the other hand, velopment, reaching from the first against those Materialists who, in hesitatingand imperfect systems down their turn, despise all philosophy, and to the rigidly consistent and calmly imagine that their views are in no reasoned Materialism of Demokritos, way a product of philosophical specu- shows us that Materialism can only lation, but are a pure result of expe- be numbered "amongst the earliest

4 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQ UITY.

crudely-inconsistent notions, which are ever being created afresh in indestructible strength by the ignorant masses. An immanent revelation, vaguely felt rather than clearly realised, lends it a deep content, while the rich embellish- ments of mythology and the venerable antiquity of tradi- tion endear it to the people. The cosmogonies of the East and of Greek antiquity present us with "ideas that are as little spiritual as they are material. They do not try to explain the world by means of a single principle, but offer us anthropomorphic divinities, primal beings half sensuous half spiritual, a chaotic reign of matter and forces in manifold changeful struggle and activity. In the presence of this tissue of imaginative ideas awakening thought calls for order and unity, and hence every system of philosophy entered upon an inevitable struggle with the theology of its time, which was conducted, according to circumstances, with more or less open animosity.

It is a mistake to overlook the presence, and indeed the momentous influence, of this struggle in Greek antiquity, although it is easy to see the origin of the mistake. If the generations of a distant future had to judge of the whole

attempts." Indeed, unless we iden- between the soul-atoms and the warm

tify it with Hylozoism and Panthe- air of Diogenes of Apollonia, despite

ism, Materialism only becomes a com- all their superficial similarity, is of

plete system when matter is conceived quite fundamental importance. The

as purely material— that is, when its latter is an absolute Reason-stuff

constituent particles are not a sort of {Vernunftstoff); it is capable in itself

thinking matter, but physical bodies, of sensation, and its movements, such

which are moved in obedience to as they are, are due to its rationality,

merely physical principles, and being Demokritos' soul-atoms move, like all

in themselves without sensations, pro- other atoms, according to purely me-

duce sensation and thought by parti- chanical principles, and produce the

cularformsof their combinations. And phenomenon of thinking beings only

thorough - going Materialism seems in a special combination mechanically

always necessarily to be Atomism, brought about. And so, again, the

since it is scarcely possible to explain "animated magnet" of Thales har-

whatever happens out of matter monises exactly with the expression

clearly and without any mixture of irävra irXripv 6eQ>v, and yet is at bot-

eupersensuous qualities and forces, torn clearly to be distinguished from

unless we resolve matter into small the way in which the Atomists at-

atoms and empty space for them to tempt to explain the attraction of

move in. The distinction, in fact, iron by the magnet.

THE EARLY ATO MISTS. 5

thought of our own time solely from the fragments of a Goethe and a Schelling, a Herder or a Lessing, they would scarcely observe the deep gulfs, the sharp distinctions of opposite tendencies that mark our age. It is character- istic of the greatest men of every epoch that they have reconciled within themselves the antagonisms of their time. So is it with Plato and Sophokles in antiquity ; and the greatest man often exhibits in his works the slightest traces of the struggles which stirred the multitude in his day, and which he also, in some shape or other, must have passed through.

The mythology which meets us in the serene and easy dress due to the Greek and Roman poets was neither the religion of the common people nor that of the scientifically educated, but a neutral territory on which both parties could meet.

The people had far less belief in the whole poetically- peopled Olympus than in the individual town or country deities whose statues were honoured in the temple with special reverence. Not the lovely creations of famed artists enthralled the suppliant crowd, but the old-fashioned, rough-hewn, yet honoured figures consecrated by tradition. Amongst the Greeks, moreover, there was an obstinate and fanatical orthodoxy, which rested as well on the interests of a haughty priesthood as on the belief of a crowd in need of help 2

This might have been wholly forgotten if Sokrates had not had to drink the cup of poison ; but Aristotle also fled

2 In view of the completely opposite variety of development than the con-

account of Zeller (Phil. d. Griechen, stitutions of the individual cities and

i. S. 44 f f. 3 Aufl. ), it may be proper countries. It was natural that the

to remark, that we may assent to the thoroughly local character of their

proposition, "The Greeks had no cultus, in conjunction with an increas-

hierarchy, and no infallible system of ing friendly intercourse, should lead

dogmas," without needing to modify to a toleration and liberality which

the representation in the text. " The was inconceivable amongst highly cre-

Greeks," we must remember, had no dulous and at the same time cen-

political unity in which these could tralised peoples. And yet, of all the

have been developed. Their system Greek efforts towards unity, those of a

of faiths exhibited an even greater hierarchic and theocratical tendency

6 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQUITY.

from Athens that the city might not a second time commit sacrilege against philosophy. Protagoras also had to flee, and his work upon the gods was publicly burnt. Anaxa- goras was arrested, and obliged to flee. Theodoras, " the

were perhaps the most important; and we may certainly consider, for ex- ample, the position of the priesthood of Delphi as no in significant exception to the rule that the priestly office con- ferred " incomparably more venera- tion than power." (Comp. Curtius, Griech. Gesch., i. p. 451; Hist, of Gr., E. T., ii. 12, in connection with the elucidations of Gerhard, Stephani, Welcker, and others as to the share of the theologians of Delphi in the extension of Bacchus-worship and the mysteries.) If there was in Greece no priestly caste, and no exclusive priestly order, there were at least priestly families, whose hereditary rights were preserved with the most inviolable legitimism, and which be- longed, as a rule, to the highest aris- tocracy, and were able to maintain their position for centuries. How great wa3 the importance of the Eleu- sinian mysteries at Athens, and how closely were these connected with the families of the Eumolpidee, the Kerykes, the Phyllidae, and so on ! (Comp. Hermann, Gottesd. Alterth., S. 31, A. 21 ; Schümann, Griech. Al- terth., ii. S. 340, u. f. 2 Aufl.) As to the political influence of these fami- lies, the fall of Alkibiades affords the clearest elucidation, although in trials which bring into play high-church and aristocratic influences in connec- tion with the religious fervour of the masses, the individual threads of the network are apt to escape observation. As to orthodoxy, this must indeed not be taken to imply a scholastic and organised system of doctrines. Such a system might perhaps have arisen if the Theocrasy of the Delphic theo- logians and of the mysteries had not come too late to prevent the spread of philosophic rationalism amongst

the aristocratic and educated classes. And so men remained content with the mystery-worships, which allowed every man on all other points to think as he pleased. But all the more in- violable remained the general belief in the sanctity and importance of these particular gods, these forms of worship, these particular sacred words and usages, so that here nothing was left to the individual, and all doubt, all attempts at unauthorised changes, all casual discussion, remained forbid- den. There was, however, without doubt, even with regard to the mythi- cal traditions, a great difference be- tween the freedom of the poets and the strictness of the local priestly tradition, which was closely con- nected with the cultus. A people which met with different gods in every city, possessed of different at- tributes, as well as a different genea- logy and mythology, without having its belief in its own sacred tradi- tions shaken thereby, must with proportionate ease have permitted its poets to deal at their own pleasure with the common mythical material of the national literature ; and yet, if liberties thus taken appeared in the least to contain a direct or indirect attack upon the traditions of the local divinities, the poet, no less than the philosopher, ran into danger. The series of philosophersnamedin the text as having been persecuted in Athens alone might easily be enlarged ; for example, by Stilpo and Theophrastos (Meier u. Schümann, Att. Prozess, S. 303, u. f.). There might be added poets like Diagorasof Melos, on whose head a price was set ; Aeschylos, who incurred the risk of his life for an alleged violation of the mysteries, and was only acquitted by the Areopagus

THE EARL Y A TO MISTS,

atheist," and probably also Diogenes of Apollonia, were prosecuted as deniers of the gods. And all this happened in humane and enlightened Athens.

From the standpoint of the multitude, every philosopher, even the most ideal, might be prosecuted as a denier of the gods ; for no one of them pictured the gods to himself as the priestly tradition prescribed.

If we cast a glance to the

in consideration of his great services ; Euripides, who was threatened with an indictment for atheism, and others. How closely tolerance and intolerance bordered upon each other in the minds of the Athenians is best seen in a passage from the speech against Andokides (which, according to Blass, Att. Beredsamkeit, S. 566 ff., is not really by Lysias, although it is a genuine speech in those proceedings). There it is urged that Diagoras of Melos had only outraged (as a foreign- er) the religion of strangers, but An- dokides had insulted that of his own city ; and we must, of course, be more angry with our fellow-countrymen than with strangers, because the lat- ter have not transgressed against their own gods. This subjective excuse must have issued in an objective ac- quittal, unless the sacrilege was espe- cially directed against the Athenian, and not against a foreign religion. From the same speech we see further, that the family of the Eumolpidse was authorised, under certain circum- stances, to pass judgment against re- ligious offenders according to a secret code whose author was entirely un- known. (That this happened under the presidency of the King Archon — comp. Meier u. Schömann, S. 117, u. f. — is for our purpose unimportant.) That the thoroughly conservative Aristophanes could make a jest of the gods, and even direct the bitterest mockery against the growing super- stition, rests upon entirely different grounds ; and that Epikuros was never persecuted is of course explained sim-

shores of Asia Minor in the

ply by his decided participation in all the external religious ceremonies. The political tendency of many of these accusations establishes rather than disproves their foundation in religious fanaticism. If the reproach of äaißei.a was one of the most effec- tual means of overthrowing even popular statesmen, not the letter of the law only, but the passionate reli- gious zeal of the masses must obvi- ously have existed ; and accordingly we must regard as inadequate the view of the relation of church and state in Schömann, Griech. Alterth., i. S. 117, 3 Aufl., as well as many of the points in Zeller's treatment of the question above referred to. And that the persecutions were not always in connection with ceremonies, but often had direct reference to doctrine and belief, appears to be quite clearly proved by the majority of the accusa- tions against the philosophers. But if we reflect upon the by no means small number of cases of which we hear in a single city and in a compa- ratively short space of time, and upon the extreme peril which they in- volved, it will scarcely appear right to say that philosophy was attacked "in a few only of its representatives." We have still rather seriously to inquire, as again in the modern philosophy of the seventeenth, eighteenth (and nineteenth ?) centuries, How far the influence of conscious or unconscious accommodation to popular beliefs be- neath the pressure of threatening- persecution has left its mark xxpon the svstems themselves ?

8 MA TER1ALISM IN ANTIQ UITY.

centuries that immediately precede the brilliant period of Hellenic intellectual life, the colonies of the Ionians, with their numerous important cities, are distinguished for wealth and material prosperity, as well as for artistic sensi- bility and refinement of life. Trade and political alliances, and the increasing eagerness for knowledge, led the inhabi- tants of Miletos and Ephesos to take long journeys, brought them into manifold intercourse with foreign feelings and opinions, and furthered the elevation of a free-thinking aristocracy above the standpoint of the narrower masses. A similar early prosperity was enjoyed by the Doric col- onies of Sicily and Magna Graecia. Under these circum- stances, we may safely assume that, long before the appear- ance of the philosophers, a freer and more enlightened conception of the universe had spread amongst the higher ranks of society.

It was in these circles of men, wealthy, distinguished, with a wide experience gained from travel, that philosophy arose. Thales, Anaximander, Herakleitos, Empedokles took a prominent position amongst their fellow-citizens, and it is not to be wondered at that no one thought of bringing them to account for their opinions. This ordeal, it is true, they had to undergo, though much later ; for in the last century the question of the atheism of Thales was eagerly handled in special monographs. 3 If we compare, in this

3 Comp. Zeller, i. S. 176, Anm. 2, reason," especially in the Stoical 3 Aufl., and the works quoted in sense, refers merely to an immanent, Marbach, Gesch. d. Phil., S. 53, not anthropomorphic, and therefore which, and that by no mere coinci- also not a personal God. Even dence, appeared at the period of the though the Stoic tradition may rest Materialist controversy of the last upon a mere interpretation of an older century. With regard to the state- tradition in the sense of their own ment of Zeller, who seems to me to system, yet it does not follow from rate Thales too low, I may observe, this that this interpretation (apart that the passage in Cicero, De Nat. from the genuineness of the words) is Deorum, i. x. 23, formerly employed also false. Judging from the con- to prove the theism of Thales, with nection, the probably genuine expres- Cicero's characteristic shallowness, sion that all things are full of gods by the expression "fmgere ex," in- may very likely be the origin of the dicates a Demiurgus standing outside notion — an expression which even the world-stuff, while God, as "world- Aristotle (De An., i. 5, 17) obviously

THE EARLY A TO MIS TS. 9

respect, the Ionic philosophers of the sixth century with the Athenians of the fifth and fourth, we shall at once be reminded of the contrast between the English sceptical movement of the seventeenth and the French of the eighteenth century. In the one case, nobody thought of drawing the people into the war of opinions ; 4 in the other, the movement was a weapon with which fanaticism was to be assaulted.

Hand in hand with this intellectual movement proceeded among the Ionians the study of mathematics and natural science. Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes busied themselves with special problems of astronomy, as well as with the explanation of the universe ; and Pythagoras transplanted the taste for mathematical and physical inquiry to the westward colonies of the Doric stock. The fact that, in the eastern portion of the Greek world, where the intercourse with Egypt, Phoenicia, Persia, was most active, the scientific movement began, speaks more de- cidedly for the influence of the East upon Greek culture than the fabulous traditions of the travels and studies of Greek philosophers. 5 The idea of an absolute originality

interprets symbolically ; so that the consistent position of Anaxagoras.

doubt indicated by tcrws refers (and So the way in -which he speaks of his

rightly) to his own interpretation doubtful merit, as also the severe

only, which is, in fact, much more censure of his inconsistency, are in

perverse and improbable than that of Aristotle only the continuation of the

the Stoics. To refute (Zeller, i. 173) fanatical zeal with which the Platonic

the view of the latter by Aristotle Sokrates, in the Phaedo, c. 46, handles

(Met. , i. 3) is unsafe, because Aris- the same point.

totle is undoubtedly there bringing 4 Comp. Buckle, History of Civili-

out the element in Anaxagoras which zation, i. 497 sqq. was related to his own philosophy, 5 Compare the lengthy refutation

that is, the separation of the world- of the views as to the rise of Greek

forming Keason, as of the cause of philosophy from Oriental speculation

Becoming, from the matter upon in Zeller, i. S. 20 ff., 3 Aufl., and the

which it works. That he is not con- concise but very careful discussion of

tent with this very element in Anax- the same question in Ueberweg, i.,

agoras, as is shown by the very next 4 Aufl., S. 32, E. T. 31. The criticism

chapter, because the transcendental of Zeller and others has for ever dis-

principle appears only occasionally, placed the cruder views that the East

and is not consistently carried out, taught philosophy to the Greeks ; on

is a necessary consequence of the the other hand, the remarks of Zeller

transitional and by no means wholly (S. 23 ff.) as to the influence of the

io MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQ U1TY.

of Hellenic culture may be justified if by this we mean originality of form, and argue the hidden character of its roots from the perfection of the flower. It becomes, how- ever, delusive if we insist upon the. negative results of the criticism of special traditions, and reject those connections and influences which, although the usual sources of history fail us, are obviously suggested by a view of the circum- stances. Political relations, and, above all, commerce, must necessarily have caused knowledge, sentiments, and ideas to flow in many ways from people to people ; and if Schiller's saying, " Euch ihr Götter gehöret der Kaufmann" (" To you, gods, belongs the merchant"), is genuinely human, and therefore valid for all time, many an intercom- munication will have been later connected by mythology with some famous names, whose true bearers have for ever been lost to memory.

Certain it is that the East, in the sphere of astronomy and the measurement of time, was ahead of the Greeks. The people of the East, too, possessed mathematical know-

common Indo-Germanic descent, and with a great religious movement in

the continual influence of neighbour- the East." Conversely, also, it is

hood, may well gain an increased sig- quite possible that particular philo-

nificance with the progress of Oriental sophical ideas may have come from

studies. Especially with regard to the East to Greece, and there have

philosophy, we may observe that been developed just because suitable

Zeller — as a result of his Hegelian intellectual circumstances had been

standpoint — obviously undervalues prepared by the Greeks' own develop-

its connection with the general his- ment. The historians will also have

tory of thought, and isolates too to adopt scientific theories. The

much the "speculative" ideas. If crude opposition of originality and

our view of the very intimate con- tradition can no longer be employed,

nection of speculation with religious Ideas, like organic germs, fly far and

rationalism, and with the beginning wide, but the right ground alone

of scientific thought, is at all correct, brings them to perfection, and often

then the stimulus to this changed gives them higher forms. And in

mode of thought may have come from this case, of course, the possibility of

the East, but may in Gi-eece, thanks the origin of Greek philosophy with-

to the more favourable soil, have out such stimulus is not excluded,

matured more noble fruits. Com- although, of course, the question of

pare the observation of Lewes, Hist, originality bears quite a new aspect,

of Phil. , i. p. 3: " It is a suggestive The true independence of Hellenic

fact that the dawn of scientific specu- culture rests in its perfection, not in

lation in Greece should be coincident its beginnings.

THE EARL Y A TO MISTS. 1 1

ledge and skill at a time when no one thought of such things as yet in Greece ; although it was in this very sphere of mathematics that the Greeks were destined to outrun all the nations of antiquity.

With the freedom and boldness of the Hellenic mind was united an innate ability to draw inferences, to enunciate clearly and sharply general propositions, to hold firmly and surely to the premisses of an inquiry, and to arrange the results clearly and luminously ; in a word, the gift of scientific deduction.

It has in our days become the fashion, especially amongst the English since Bacon, to depreciate the value of de- duction. Whewell, in his well-known "History of the Inductive Sciences," is constantly unjust to the Greek philosophers, and notably to the Aristotelian school. He discusses in a special chapter the causes of what he regards as their failure, continually applying to them the standard of our own time and of our modern scientific position. We must, however, insist that a great work had to be done before the uncritical accumulation of observations and traditions could be transformed into our fruitful method of experiment. A school of vigorous thinking was first to arise, in which men were content to dispense with pre- misses for the attainment of their proximate object. This school was founded by the Greeks, and it was they who gave us, at length, the most essential basis of deductive processes, the elements of mathematics and the principles of formal logic. 6 The apparent inversion of the natural

6 Although the modern Aristo- Notion, and frequently, indeed, con-

telians are so far right that the essen- tradict it. Much, however, as it may

tial feature of the Aristotelian Logic, now be the fashion to despise Formal

from its author's standpoint, is not Logic, and to over-estimate the meta-

the Formal Logic, hut the logico-meta- physical doctrine of the Notion, yet

physical Theory of Knowledge. At a calm consideration establishes be-

the same time he has also left us cer- yond question that the fundamental

tain elements of Formal Logic, of principles of Formal Logic are alone

course only collected and developed demonstrated strictly as >the prin-

by him, which, as I hope to show in ciples of Mathematics, and these only

a later work, have a merely external so far as they are not (as is the doctrine

connection with the principle of his of the conclusions from modal judg-

12 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQUITY.

order, in the fact that mankind learnt to deduce correctly before they learnt to find correct starting-points from which to reason, can be seen to be really natural only from a psychological survey of the whole history of thought.

Of course, speculation upon the universe and its in- ter-relations was not, like mathematical inquiry, able to reach results of permanent value : innumerable vain at- tempts must first shake the confidence with which men ventured upon this ocean before philosophic criticism could succeed in showing how what was apparently the same method, brought about in the one case sure progress, and in the other mere blind beating about the bush.? And yet, even in the last few centuries, nothing so much con- tributed to lead philosophy, which had just broken off the Scholastic yoke, into new metaphysical adventures, as the intoxication caused by the astonishing advances of mathe- matics in the seventeenth century. Here also, of course, the error furthered again the progress of culture ; for the systems of Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz, not only brought with them numerous incitements to thought and inquiry, but it was these systems that first really displaced the Scholasticism already doomed by the sentence of criti- cism, and thereby made way for a sounder conception of the world.

In Greece, however, men succeeded for once in freeing the vision from the mist of wonder, and in transferrins; their study of the world from the dazzling fable-land of religious and poetical ideas to the sphere of reason and of sober theory. This, however, could, in the first place, only be accomplished by means of Materialism ; for external things lie nearer to the natural consciousness than the "Ego," and even the Ego, in the ideas of primitive peoples, is connected rather with the body than with the shadowy

merits) adulterated and corrupted by Vera. Einl., especially the passage iii.

the Aristotelian Metaphysic. S. 38, Hartenstein. A full discussion

7 Compare the formulation of the of the questions of method will be

same problem in Kant, Kritik d. rein, found in the Second Book.

THE EARLY A TO MISTS. 13

Soul, the product of sleeping and of waking dreams, that they supposed to inhabit the body. 8

The proposition admitted by Voltaire, bitter opponent as he otherwise was of Materialism, " I am a body, and I think," would have met with the assent also of the earlier Greek philosophers. When men began to admire the de- sign in the universe and its component parts, especially in the organic sphere, it was a late representative of the Ionic natural philosophy, Diogenes of Apollonia, who identified the reason that regulated the world with the original sub- stance, Air.

If this substance had been conceived as sentient, and its sensations supposed to become thoughts by means ot the growing complexity and motion of the substance, a vigorous Materialism might have been developed in this direction ; perhaps a more durable one than that of the Atomists. But the reason-matter of Diogenes is omni- scient ; and so the last puzzle of the world of appearances is again at the outset hopelessly confused.9

The Atomists broke through the circle of this petitio principii in fixing the essence of matter. Amongst all the properties of things, they assigned to matter only the simplest, and those indispensable for the presentation of something in time and space, and endeavoured from these alone to develop the whole aggregate of phenomena. In

8 Comp, the article " Seelenlehre " tellectual life of man from a series in the Encyc. des Ges. Erziehungs- of sentient conditions in his corpo- und Unterrichtswesens, Bd. viii. real atoms, we strike upon the same S. 594. rock as the Atomism of Demokritos,

9 Comp. Note 1. Details as to when he builds tip, e.g., a sound or a Diogenes of Apollonia in Zeller, i. colour from the mere grouping of 218 ff. The possibility here sug- atoms in themselves neither lumin- gested of an equally consequent Ma- ous nor sounding ; while, if we trans- terialism without Atomism will be fer again the whole contents of human considered in the Second Book, when consciousness, as an internal condi- we discuss the views of Ueberweg. tion, to a single atom — a theory which Now we will only observe that a recurs in modern philosophy in the third possibility, which also was most various modifications, though it never developed in antiquity, lies in was so far from the mind of the an- the theory of sentient atoms ; but cients— then Materialism is trans- here, as soon as we build up the in- formed into a mechanical Idealism.

14 MA TERIAL1SM IN ANTIQ UITY.

this respect the Eleatics, it may be, had prepared the way for them, that they distinguished the persistent matter that is known in thought alone as the only real existence from the deceitful change of sense-appearances ; and the referring of all sense qualities to the manner of combina- tion of the atoms may have been prepared for by the Pythagoreans, who recognised the essence of things in number, that is, originally in the numerically fixed rela- tions of form in bodies. At all events, the Atomists sup- plied the first perfectly clear conception of what is to be understood by matter, or the substratum of all phenomena. "With the introduction of this notion, Materialism stood complete as the first perfectly clear and consequent theory of all phenomena.

This step was as bold and courageous as it was metho- dically correct ; for so long as men started at all from the external objects of the phenomenal world, this was the only way of explaining the enigmatical from the plain, the complex from the simple, and the unknown from the known; and even the insufficiency of every mechanical theory of the world could appear only in this way, because this was the only way in which a thorough explanation could be reached afc all.

With few great men of antiquity can history have dealt so despitefully as with Demokritos. In the distorted picture of unscientific tradition, almost nothing appears of him except the name of the " laughing philosopher," while figures of incomparably less importance extend themselves at full length. So much the more must we admire the tact with which Bacon, ordinarily no great hero in his- torical learning, chose exactly Demokritos out of all the philosophers of antiquity, and awarded him the premium for true investigation, whilst he considers Aristotle, the philosophical idol of the Middle Ages, only as the originator of an injurious appearance of knowledge, falsely so called, and of an empty philosophy of words. Bacon may have been unfair to Aristotle, because he was lacking in that

THE EARLY A TO MISTS. 1 3

historical sense which, even amidst gross errors, recognises the inevitable transition to a deeper comprehension of the truth. In Demokritos he found a kindred spirit, and judged him, across the chasm of two thousand years, much as a man of his own age. In fact, shortly after Bacon, and in the very shape which Epikuros had given it, Atomism became the foundation of modern natural science.

Demokritos was a citizen of the Ionian colony of Ab- dera on the Thracian coast. The " Abderites " had not as yet earned the reputation of " Gothamites," which they enjoyed in the later classical times. The prosperous commercial city was wealthy and cultivated : Demokritos' father was a man of unusual wealth ; there is scarcely room to doubt that the highly-gifted son enjoyed an excellent education, even if there is no historical foundation for the story that he was brought up by Persian Magi. 10

10 It must not be supposed from this that I concur entirely in a kind of criticism employed with regard to this tradition by Mullach, Zeller, and others. It is not right to reject im- mediately the whole story of the stay of Xerxes in Abdera, merely because of the ridiculous exaggeration of Valerius Maximus. and the inac- curacy of a passage in Diogenes. We know from Herodotus that Xerxes made a halt in Abdera, and was very much pleased with his stay there (viii." 120 ; probably the passage which Diogenes had in his mind). That upon this occasion the king and his court would quarter themselves upon the richest citizens of the place is a matter of course ; and that Xerxes had his most learned Magi in his train is again historical. But we are so far from being justified, therefore, in supposing even an early stimulat- ing influence to have been exercised by these Persians upon the mind of an inquisitive boy, that we might rather argue the contrary, since the great internal probability might only the more easily enable the germ of

these stories to develop itself, from mere conjectures and combinations, into a factitious tradition, while the late appearance of the story, in un- trustworthy authors, makes its exter- nal evidence very slight. As to the associated question of the age of Demokritos, in spite of all the acute- ness spent in its treatment (comp. Frei, Qusestiones Protagoreae, Bonnse, 1845, Zeller, i. S. 684 sqq., Anm. 2, and 783 sqq., Anm. 2), a successful answer in defence of the view of K. P. Hermann, which we followed in the ist edition, is by no means rendered impossible. Internal evidence (comp. Lewes, Hist. Phil., i. 97) declares, however, rather for placing Demo- kritos later. The view, indeed, of Aristotle, who makes Demokritos the originator of the Definitions, con- tinued by Sokrates and his contem- poraries (comp. Zeller, i. S. 686 Anm. ), must not be too hastily ad- opted, since Demokritos, at all events, only began to develop his doctrines when he had reached mature age. If, then, we place this work of So- krates at the height of his intercourse

i6 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQ UITY.

Demokritos appears to have spent his whole patrimony in the " grand tour" which his zeal for knowledge induced him to make. Eeturning in poverty, he was supported by his brother, but soon, by his successful predictions in the sphere of natural philosophy, he gained the reputation of being a wise and heaven-inspired man. Finally, he wrote his great work, the " Diakosmos," — the public reading of which was rewarded by his native city with a gift of one hundred, according to others, five hundred talents, and with the erection of commemorative columns.

The year of Demokritos' death is uncertain, but there is a general admission that he reached a very advanced age, and died cheerfully and painlessly.

A great number of sayings and anecdotes are connected with his name, though the greater portion of them have no particular import for the character of the man to whom they relate. Especially is this so of those which sharply contrast him as the " laughing " with Herakleitos as the " weeping " philosopher, since they see nothing in him but the merry jester over the follies of the world, and the holder of a philosophy which, without losing itself in profundities, regards everything from the good side. As little pertinent are the stories that represent him merely as a Polyhistor, or even as the possessor of mystic and secret doctrines. "What in the crowd of contradictory reports as to his person is most certain is, that his whole life was devoted to scien- tific investigations, which were as serious and logical as they were extensive. The collector of the scattered frag- ments which are all that remain to us of his numerous works, regards him as occupying the first place for genius and knowledge amongst all the philosophers before his birth, and goes so far as to conjecture that the Stagirite has largely to thank a study of the works of Demokritos for the fulness of knowledge which we admire in him. 11

with the Sophists, about 425, Demo- n Mullach, Fragm. Phil. Graec, Par.

kritos could, at all events, be as old 1869, p. 338: "Fuit il'le quarnquam

as Sokrates, but, of course, not have in caeteris dissimilis, in hoc sequabili

been born aa late as 460. omnium artium studio simillinius

THE EARL Y A TO MIS TS. 1 7

It is significant that a man of such extensive attain- ments has said that " we should strive not after fulness of knowledge, but fulness of understanding ;" 12 and where he speaks, with pardonable complacence, of his achievements, he dwells not upon the number and variety of his writings, but he boasts of his personal observation, of his inter- course with other learned men, and of his mathematical method. "Among all my contemporaries," he says, "I have travelled over the largest portion of the earth in search of things the most remote, and have seen the most climates and countries, heard the largest number of thinkers, and no one has excelled me in geometric construction and demonstration — not even the geometers of the Egyptians, with whom I spent in all five years as a guest." 13

Amongst the circumstances which have caused Demo- kritos to fall into oblivion, ought not to be left unmen- tioned his want of ambition and distaste for dialectic discussion. He is said to have been in Athens without making himself known to one of its philosophers. Amongst his moral aphorisms we find the following : " He who is fond of contradiction and makes many words is incapable of learning anything that is right."

Such a disposition suited little with the city of the Sophists, and certainly not with the acquaintance of a Sokrates or a Plato, whose whole philosophy was developed in dialectic word-play. Demokritos founded no school.

His words were, it appears, more eagerly copied from than copied out; and his whole philosophy was finally absorbed by Epikuros. Aristotle mentions him frequently

Aristotelis. Atque haud scio an Sta- mark that it shows "that Demo-

girites illam qua reliquos philosophos kritos in this respect had little to

superat eruditionem aliqua ex parte learn from foreigners, "goes much too

Democriti librorum lectioni debu- far. It is not even certain from De-

erit." mokritos's observation that he was

12 Zeller, i. S. 746, Mullach, Fr. superior to the " Harpedonaptae " Phil., p. 349, Fr. 140-142. on his arrivalin Egypt; but even if

13 Fragm. Varii Arg. 6, in Mullach, he were, he might, it is obvious, still Fragm. Phil., pp. 370 sqq. ; comp, learn much from them.

Zeller, i. 688, Anm., where the re-

VOL. I. B

i8 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQUITY.

with respect ; but lie cites him, for the most part, only when he attacks him, and this he by no means always does with a fitting objectivity and fairness.14 How often he has bor- rowed from him without naming him we do not know. Plato speaks of him nowhere, though it is a matter of dis- pute whether, in some places, he has not controverted his opinions without mention of his name. Hence arose, it may be, the story that Plato in fanatical zeal would have liked to buy up and burn all the works of Demokritos. 1 ^

In modern times Eitter, in his " History of Philosophy," emptied much anti-materialistic rancour upon Demo- kritos's memory; and we may therefore rejoice the more at the quiet recognition of Brandis and the brilliant and convincing defence of Zeller; for Demokritos must, in truth, amongst the great thinkers of antiquity, be num- bered with the very greatest.

As to the doctrines of Demokritos, we are, indeed, better informed than we are as to the views of many a philoso- pher whose writings have come to us in greater fulness. This may be ascribed to the clearness and cons cutiveness of his theory of the world, which permits us to add with the greatest ease the smallest fragment to the whole. Its core is Atomism, which, though not of course invented by him, through him certainly first reached its full development. We shall prove in the course of our history of Materialism that the modern atomic theory has been gradually devel- oped from the Atomism of Demokritos. We may consider the following propositions as the essential foundations of Demokritos's metaphysic.

14 Comp., e.g., the way in which nomenon as such. See Zeller, i.

Aristotle, De Aninia, i. 3, attempts to 742 u. f .

render ridiculous the doctrine of De- 15 However incredible such fanati- mokritos as to the movement of the cism may appear to us, it is quite con- body by the soul ; further, the inter- sonant with the character of Plato ; polation of chance as a cause of move- and as Diogenes' authority for this ment, which is gently censured by statement is no less a person than Zeller, i. 710, 711, with Anm. 1, and Aristoxenos, it may be that we have the statement that Demokritos had here something more than a " story." attributed truth to the sensible phe- Cf.Ueberweg, i. 4 Aufl., S. 73, E. T. 68.

THE EARL Y A TO MISTS. 19

I. Out of nothing arises nothing ; nothing that is can he destroyed. All change is only combination and separa- tion of atoms. 1 ®

This proposition, which contains in principle the two great doctrines of modern physics — the theory of the indestructibility of matter, and that of the persistence of force (the conservation of energy) — appears essentially in Kant as the first " analogy of experience : " " In all changes of phenomena matter is permanent, and the quan- tity thereof in nature is neither increased nor diminished." Kant finds that in all times, not merely the philosopher, but even common sense, has presupposed the permanence of matter. The doctrine claims an axiomatic validity as a necessary presupposition of any regulated experience at all, and yet it has its history ! In reality, to the natural man, in whom fancy still overrides logical thought, nothing is more familiar than the idea of origin and disappearance, and the creation " out of nothing " in the Christian dogma is scarcely ever the first stumbling-block for awakening scepticism.

With philosophy the axiom of the indestructibility of matter comes, of course, to the front, although at first it may be a little veiled. The "boundless" (aireipov) 01 Anaximander, from which everything proceeds, the divine primitive fire of Herakleitos, into which the changing world returns, to proceed from it anew, are incarnations of persistent matter. Parmenides of Elea was the first to deny all becoming and perishing. The really existent is to the Eleatics the only "All," a perfectly rounded sphere, in which there is no change nor motion ; all altera- tion is only phenomenal. But here arose a contradiction between appearance and being, in face of which philosophy could not be maintained. The one-sided maintenance of the one axiom injured another: "Nothing is without cause." How, then, from such unchanging existence could the phenomenal arise ? To this was added the

16 See the proofs in Zeller, i. 691, Anm. 2.

so MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQ UITY.

absurd denial of motion, which, of course, led to innumer- able logomachies, and so furthered the development of Dialectic. Empedokles and Anaxagoras drop this absur- dity, inasmuch as they refer all becoming and perishing to combination and separation. Only first by means of Atomism was this thought fully represented, and made the corner-stone of a strictly mechanical theory of the universe ; and it was further necessary to bring into con- nection the axiom of the necessity of everything that happens.

II. " Nothing happens by chance, but everything through a cause and of necessity "17

This proposition, already, according to a doubtful tradi- tion, held by Leukippos, must be regarded as a decided negation of all teleology, for the "cause" (X070?) is nothing but the mathematico-mechanical law followed by the atoms in their motion through an unconditional necessity. Hence Aristotle complains repeatedly that Demokritos, leaving aside teleological causes, had ex- plained everything by a necessity of nature. This is exactly what Bacon praises most strongly in his book on the "Advancement of Learning," in which, in other re- spects, he prudently manages to restrain his dislike of the Aristotelian system (lib. iii. c. 4).

This genuinely materialistic denial of final causes had thus, we see, led, in the case of Demokritos, to the same misunderstandings that, in our own day, Materialism finds almost everywhere predominant — to the reproach that he believed in a blind chance. Although no confusion is more common, nothing can be more completely opposite than chance and necessity ; and the explanation lies in this, that the notion of necessity is entirely definite and absolute, while that of chance is relative and fluctuating.

When a tile falls upon a man's head while he is walking

17 Fragm. Phys., 41, Mullach, p. aXXd irdvTa £k \6yov re /cat vir dv- 365 : <! ovdev XPVP-a fxdrt]v ylvcrai dytcqs.

THE EARLY ATO MISTS. 21

down the street, this is regarded as an accident ; and yet no one doubts that the direction of the wind, the law of gravitation, and other natural circumstances, fully deter- mined the event, so that it followed from a physical neces- sity, and also from a physical necessity must, in fact, strike any head that at the particular moment happened to be on the particular spot.

This example clearly shows that the assumption of chance is only a partial denial of final cause. The falling of the stone, in our view, could have had no reasonable cause if we call it an accident.

If, however, we assume, with the philosophy of the Chris- tian religion, an absolute predestination, we have as com- pletely excluded chance as by the assumption of absolute causality. In this point the two most consequent theories entirely coincide, and both leave to the notion of chance only an arbitrary use, practically no use whatever. We call accidental anything the cause or object of which we do not know, merely for the sake of brevity, and therefore quite unphilosophically ; or we start from a one-sided standpoint, and maintain, in the face of the teleologist, the accidental theory of events, in order to get rid of final causes, while we again have recourse to this same theory of chance so soon as we have to deal with the principle of sufficient reason.

And rightly, so far as physical investigation or any strict science is concerned ; for it is only from the side of efficient causes that the phenomenal world is accessible to inquiry, and all infusion of final causes, which are by way of sup- plement placed above or beside the nature forces subject to necessity — that is, those operating with the utmost regularity of ascertained laws — has no significance what- ever, except as a partial negation of science, an arbitrary exclusion of a sphere not yet subjected to thorough inves- tigation. 18

18 Of course, this is also true of the to set aside the fundamental principle most recent and the boldest attempt of all scientific thought— the 'Plnlo-

22 MA TERIALISM IN ANTIQ UITY.

An absolute teleology, however, Bacon was willing to admit, although, his conception of it was not sufficiently clear. This notion of a design in the totality of nature, which in detail only gradually becomes intelligible to us by means of efficient causes, does not refer, of course, to any absolutely human design, and therefore not to a design in- telligible to man in its details. And yet religions need an absolutely anthropomorphic design. This is, however, as great an antithesis to natural science as poetry is to his- torical truth, and can, therefore, like poetry, only maintain its position in an ideal view of things.

Hence the necessity of a rigorous elimination of final causes before any science at all can develop itself. If we ask, however, whether this was the impelling motive for Demokritos when he made an absolute necessity the foundation of all study of nature, we cannot here enter upon all the questions thus suggested : only of this there can be no doubt, that the chief point was this, viz., a clear recognition of the postulate of the necessity of all things as a condition of any rational knowledge of nature. The origin of this view is, however, to be sought only in the study of mathematics, the influence of which in this direc- tion has in later times also been very decided. 19

III. Nothing exists hut atoms and empty space : all else is only opinion.

Here we have in the same proposition at once the strong and the weak side of all Atomism. The founda- tion of every rational explanation of nature, of every great discovery of modern times, has been the reduction of phenomena into the motion of the smallest particles ; and undoubtedly even in classical ages the most important results might have been attained in this direction, if the reaction that took its rise in Athens against the devo- tion of philosophers to physical science had not so dis-

sopliy of the Unconscious!' We shall Book of returning to this late fruit have an opportunity in the Second of our speculative Romanticism. 19 Fragm. Phys., i, Mullach, p. 357.

THE EARLY ATO MISTS. 23