Cabinet of curiosities

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 14:14, 6 January 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) (→Further reading) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 14:15, 6 January 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) (→List of works depicting cabinets of curiosities) Next diff → |

||

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

| ==List of works depicting cabinets of curiosities== | ==List of works depicting cabinets of curiosities== | ||

| - | *''[[Kleinodien-Schrank]]''[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Johann_Georg_Hainz_001.jpg] (1666) - [[Johann Georg Hainz]] | + | *''[[Kleinodien-Schrank]]'' (1666) by Johann Georg Hainz |

| - | *''[[Eine Kunstkammer]]''[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Frans_Francken_d._J._009.jpg] (1618) - [[Frans Francken d.J]] | + | *''[[Eine Kunstkammer]]'' (1618) by Frans Francken d.J |

| + | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 14:15, 6 January 2022

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Cabinets of curiosities (also known as Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, or wonder-rooms) were encyclopedic collections of types of objects whose categorical boundaries were, in Renaissance Europe, yet to be defined. Modern terminology would categorize the objects included as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings) and antiquities. Besides the most famous, best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe, formed collections that were precursors to museums.

An early book on the subject is Die Kunst- und Wunderkammern der Spätrenaissance (1908) by Julius von Schlosser.

Contents |

History

The term cabinet originally described a room rather than a piece of furniture. The classic style of cabinet of curiosities emerged in the sixteenth century, although more rudimentary collections had existed earlier. The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576-1612), housed in the Hradschin at Prague was unrivalled north of the Alps; it provided a solace and retreat for contemplation that also served to demonstrate his imperial magnificence and power in symbolic arrangement of their display, ceremoniously presented to visiting diplomats and magnates. Rudolf's uncle, Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria also had a collection, with a special emphasis on paintings of people with interesting deformities, which remains largely intact as the Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Austria.

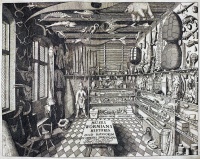

The earliest pictorial record of a natural history cabinet is the engraving in Ferrante Imperato's Dell'Historia Naturale (1599). It serves to authenticate its author's credibility as a source of natural history information, in showing his open bookcases at the right, in which many volumes are stored lying down and stacked, in the medieval fashion, or with their spines upward, to protect the pages from dust. Some of the volumes doubtless represent his herbarium. Every surface of the vaulted ceiling is occupied with preserved fishes, stuffed mammals and curious shells, with a stuffed crocodile suspended in the centre. Examples of corals stand on the bookcases. At the left, the room is fitted out like a studiolo with a range of built-in cabinets whose fronts can be unlocked and let down to reveal intricately fitted nests of pigeonholes forming architectural units, filled with small mineral specimens. Cabinet-makers serving the luxury trades of Florence and Antwerp were beginning to produce moveable cabinets with similar architectural interior fittings, which could be set upon a carpet-covered table or on a purpose-built stand. Above them, stuffed birds stand against panels inlaid with square polished stone samples, doubtless marbles and jaspers or fitted with pigeonhole compartments for specimens. Below them, a range of cupboards contain specimen boxes and covered jars.

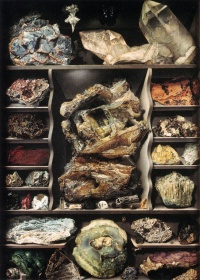

Two of the most famously described 17th century cabinets were those of Ole Worm, known as Olaus Wormius (1588-1654), and Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680). These seventeenth-century cabinets were filled with preserved animals, horns, tusks, skeletons, minerals, as well as other types of equally fascinating man-made objects: sculptures wondrously old, wondrously fine or wondrously small; clockwork automata; ethnographic specimens from exotic locations. Often they would contain a mix of fact and fiction, including apparently mythical creatures. Worm's collection contained, for example, what he thought was a Scythian Lamb, a woolly fern thought to be a plant/sheep fabulous creature. However he was also responsible for identifying the narwhal's tusk as coming from a whale rather than a unicorn, as most owners of these believed. The specimens displayed were often collected during exploring expeditions and trading voyages.

Cabinets of curiosities would often serve scientific advancement when images of their contents were published. The catalog of Worm's collection, published as the Museum Wormianum (1655), used the collection of artifacts as a starting point for Worm's speculations on philosophy, science, natural history, and more.

In 1587 Gabriel Kaltemarckt advised Christian I of Saxony that three types of item were indispensable in forming a "Kunstkammer" or art collection: firstly sculptures and paintings; secondly "curious items from home or abroad"; and thirdly "antlers, horns, claws, feathers and other things belonging to strange and curious animals" (Gutfleish B and Menzhausen J). When Albrecht Dürer visited the Netherlands in 1521, apart from artworks he sent back to Nuremberg various animal horns, a piece of coral, some large fish fins and a wooden weapon from the East Indies. The highly characteristic range of interests represented in Frans II Francken's painting of 1636 (illustration, left) shows paintings on the wall that range from landscapes, including a moonlit scene— a genre in itself— to a portrait and a religious picture (the Adoration of the Magi) intermixed with preserved tropical marine fishes and a string of carved beads, most likely amber, which is both precious and a natural curiosity. Sculpture both classical and secular (the sacrificing Libera) and modern and religious (Christ at the Column) are represented, while on the table are ranged, among the exotic shells (including some tropical ones and a shark's tooth): portrait miniatures, gem-stones mounted with pearls in a curious quatrefoil box, a set of sepia chiaroscuro woodcuts or drawings, and a small still-life painting leaning against a flower-piece, coins and medals — presumably Greek and Roman — and Roman terracotta oil-lamps, curious flasks, and a blue-and-white Ming porcelain bowl.

The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford inherited the collection of Elias Ashmole, itself largely derived from John Tradescant the elder and his son John the younger. Parts of this are still displayed together, giving a good sense of the diversity of these collections. What was left of the famous and unique complete stuffed Dodo was passed to the new Pitt Rivers Museum in the nineteenth century. An important Native American artifact, Chief Powhatan's Mantle, the cloak of the father of Pocohontas, remains in the collection.

Obviously cabinets of curiosities were limited to those who could afford to create and maintain them. Many monarchs, in particular, developed large collections. A rather under-used example, stronger in art than other areas, was the Studiolo of Francesco I, the first Medici Grand-Duke of Tuscany. Frederick III of Denmark, who added Worm's collection to his own after Worm's death, was another such monarch. A third example is the Kunstkamera founded by Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg in 1727. Many items were bought in Amsterdam from Albertus Seba and Frederik Ruysch. The fabulous Habsburg Imperial collection, included important Aztec artifacts, including the feather head-dress or crown of Montezuma now in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna.

Similar collections on a smaller scale were the complex Kunstschränke produced in the early 17th century by the Augsburg merchant, diplomat and collector Philipp Hainhofer. These were cabinets in the sense of pieces of furniture, made from all imaginable exotic and expensive materials and filled with contents and ornamental details intended to reflect the entire cosmos on a miniature scale. The best preserved example is the one given by the city of Augsburg to King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in 1632, which is kept in the Museum Gustavianum in Uppsala.

The juxtaposition of such disparate objects, according to Bredekamp's analysis (Bredekamp 1995) encouraged comparisons, finding analogies and parallels and favoured the cultural change from a world viewed as static to a dynamic view of endlessly transforming natural history and a historical perspective that led in the seventeenth century to the germs of a scientific view of reality.

A late example of the juxtaposition of natural materials with richly-worked artifice is provided by the Grünes Gewölbe, the "Green Vaults" formed by Augustus the Strong in Dresden to display his chamber of wonders. The "Enlightenment Gallery" in the British Museum, installed in the former "Kings Library" room in 2003 to celebrate the 250th anniverary of the museum, aims to recreate the abundance and diversity that still characterized museums in the mid-18th century, mixing shells, rock samples and botanical specimens with a great variety of artworks and other man-made objects from all over the world.

Notable collections started in this way

- Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Austria remain largely intact

- Ashmolean Museum Oxford — Ashmole and Tradescant collections

- Boerhaave Museum in Leiden

- Kunstkamera in Saint Petersburg, Russia

- British Museum London — Sir Hans Sloane's and other collections

- Teylers Museum in Haarlem

- Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden

- Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford, England) — Ex-Ashmolean Dodo

- Fondation Calvet, Avignon

Collectors in the Low Countries

- Bernardus Paludanus

- Nicolaes Witsen

- Simon Schijnvoet bezat vier kabinetten geordend volgens de vier elementen.

- Levinus Vincent, Wondertooneeel der Nature (catalogus), Haarlem, 1706.

- Gisbert Cuper

- Jan Swammerdam

- Abraham Gorlaeus

- Gerard van Papenbroek

- Albertus Seba

- Frederik Ruysch

List of works depicting cabinets of curiosities

- Kleinodien-Schrank (1666) by Johann Georg Hainz

- Eine Kunstkammer (1618) by Frans Francken d.J

See also

_is_by_Willem_Kalf.jpg)