Madeleine de Scudéry

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 11:19, 25 August 2023 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 11:20, 25 August 2023 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) Next diff → |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| | style="text-align: left;" | | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| - | "The whole romance is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of [[Boileau]], that when one of Mad. [[Scudery]]'s characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the furniture."--''[[History of Fiction (John Colin Dunlop)|History of Fiction]]'' (1814) by John Colin Dunlop | + | "The [[Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa|whole romance]] is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of [[Boileau]], that when one of [[Madeleine de Scudéry|Mad. Scudery]]'s characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the [[furniture]]."--''[[History of Fiction (John Colin Dunlop)|History of Fiction]]'' (1814) by John Colin Dunlop |

| <hr> | <hr> | ||

| "She expresses so delicately the most difficult [[feeling]]s to [[express]] and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the [[loving]] [[heart]] … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--[[Madeleine de Scudéry]] describing herself in vol. 10 of ''[[Artamène]]'', using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG | "She expresses so delicately the most difficult [[feeling]]s to [[express]] and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the [[loving]] [[heart]] … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--[[Madeleine de Scudéry]] describing herself in vol. 10 of ''[[Artamène]]'', using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG | ||

Revision as of 11:20, 25 August 2023

|

"The whole romance is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of Boileau, that when one of Mad. Scudery's characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the furniture."--History of Fiction (1814) by John Colin Dunlop "She expresses so delicately the most difficult feelings to express and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the loving heart … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--Madeleine de Scudéry describing herself in vol. 10 of Artamène, using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG A lover who is afraid of thieves --Mademoiselle de Scudéri (1819) is a novella by E. T. A. Hoffmann |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Madeleine de Scudéry (1607 – 1701) was a French writer best known for the novel sequence Clelie (1654-1660).

Her works also demonstrate such comprehensive knowledge of ancient history that it is suspected she had received instruction in Greek and Latin. In 1637, following the death of her uncle, Scudéry established herself in Paris with her brother. Georges de Scudéry became a playwright. Madeleine often used her older brother's name, George, to publish her works. She was at once admitted to the Hôtel de Rambouillet coterie of préciosité, and afterwards established a salon of her own under the title of the Société du samedi (Saturday Society). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of Sapho or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first bluestocking of France and of the world. She formed a close romantic relationship with Paul Pellisson which was only ended by his death in 1693. She never married.

Contents |

Influence

The romances of Madeleine de Scudéry gained great influence with plots situated in the ancient world and content taken from life. The famous author told stories of her friends in the literary circles of Paris and developed their fates from volume to volume of her serialised production. Readers of taste bought her books, as they offered the finest observation of human motives, characters taken from life, excellent morals regarding how one should and should not behave if one wanted to succeed in public life and in the intimate circles she portrayed.

Comment by Sainte-Beuve

In Portraits Of The Seventeenth Century Historic And Literary (1909)[1] Sainte-Beuve said that her books are unreadable:

- It is true that her books are unreadable now and exasperating to literary taste; but we should remember that she made part of a great pioneer work, in which all the actors laid stepping-stones by which social life, literature, manners, refinement, the status of women, were to rise, and rise rapidly to higher things. With this before our minds we can overlook the Carte du Tendre (Map of the Country of Tenderness) which, by the way, was only a bit of private nonsense which her friends unwisely persuaded her to put into Clelie and turn to her solid advice to women, given in her Grand Cyrus:

But Saint-Beuve also commends her for encouraging women to learn how to read:

- I leave you to judge whether I am wrong in wishing that women should know how to read, and read with application. There are some women of great natural parts who never read anything; and what seems to me the strangest thing of all is that those intelligent women prefer to be horribly bored when alone, rather than accustom themselves to read, and so gather company in their minds by choosing such books, either grave or gay, as suit their inclinations. It is certain that reading enlightens the mind so clearly and forms the judgment so well that without it conversation can never be as apt or as thorough as it might be. ... I want women to be neither learned nor ignorant, but to employ a little better the advantages that nature has given them, I want them to adorn their minds as well as their persons. This is not incompatible with their lives; there are many agreeable forms of knowledge which women may acquire thoroughly without departing from the modesty of their sex, provided they make good use of them. And I therefore wish with all my heart that women's minds were less idle than they are, and that I myself might profit by the advice I give to others."

- (tr. Katherine Prescott Wormeley)

Works

Her lengthy novels, such as Artamène, ou le Grand Cyrus (10 vols., 1648-53), Clélie (10 vols., 1654-61), Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa (4 vols., 1641), Almahide, ou l'esclave reine (8 vols., 1661-3) were the delight of Europe, commended by other literary figures such as Madame de Sévigné. Artamène, which contains about 2.1 million words, ranks as one of the longest novels ever written. These stories derive their length from endless conversations and, as far as incidents go, successive abductions of the heroines, conceived and told decorously.

Scudéry's novels are usually set in the classical world or the Orient, but their language and action reflect fashionable ideas of the 17th century, and the characters can be identified with Mademoiselle de Scudéry's contemporaries. In Clélie, Herminius represents Paul Pellisson; Scaurus and Lyriane were Paul Scarron and his wife (who became Mme de Maintenon); and in the description of Sapho in vol. 10 of Le Grand Cyrus the author paints herself.

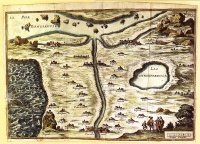

In Clélie, Scudéry invented the famous Carte du Tendre, a map of an Arcadia where the geography is all based around the theme of love: the river of Inclination flows past the villages of "Billet Doux" (Love Letter), "Petits Soins" (Little Trinkets) and so forth. Scudéry was a skilled conversationalist; several volumes purporting to report her conversations upon various topics were published during her lifetime. She had a distinct vocation as a pedagogue. She could moralize—a favourite employment of the time—with sense and propriety.

Controversial in her own era, Mlle de Scudéry was satirized by Molière in his plays Les Précieuses ridicules (1659) and Les Femmes savantes (1672) and by Antoine Furetière in his Roman Bourgeois (1666).

The 19th century German short-story writer E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote what is usually referred to as the first German-language detective story, featuring Scudéry as the central figure. "Das Fräulein von Scuderi" (Mademoiselle de Scudery) is still widely read today, and is the origin of the "Cardillac syndrome" in psychology.

Biography

Born at Le Havre, Normandy, in northern France, she is said to have been very plain as well as without fortune, but she was very well educated. Establishing herself at Paris with her brother, she was at once admitted to the Hôtel de Rambouillet coterie, and afterwards established a salon of her own under the title of the Société du samedi (Saturday Society). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of Sapho or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first bluestocking of France and of the world. She formed a close friendship with Paul Pellisson which was only ended by his death in 1693.

Later years

Madeleine survived her brother by more than thirty years, and in her later days published numerous volumes of conversations, to a great extent extracted from her novels, thus forming a kind of anthology of her work. She outlived her vogue to some extent, but retained a circle of friends to whom she was always the "incomparable Sapho."

Her Life and Correspondence was published at Paris by MM. Rathery and Boutron in 1873.

Summaries of the stories and keys to the characters may be found in Heinrich Körting, Geschichte des französischen Romans im 17ten Jahrhundert (second edition, Oppeln, 1891).

Description of her life and work by Dunlop in History of Fiction

The most voluminous writer of heroic romance is Mmle de Scudery, whose numerous productions amount to near fifty volumes. Madeleine de Scudery was bom in 1607 at Havre, but came at an early period of her life to Paris, where she chiefly resided till her death, which happened in 1701, when she was in the ninety-fourth year of her age.

The Hotel de Rambouillet seems to have been the nursery in which the first blossoms of her genius were fostered ; and it must be acknowledged, that if the suc- ceeding fruits were not of the finest flavour, their bulk was such as almost to render competition hopeless. They at least procured her admission into all the academies where women could be received. She corresponded with Queen Christina, from whom she received a pension with marks of particular favour, and during several years her house was attended by a sort of literary club, which at that time seems to have been the highest ambition of the women of letters at Paris.

These honours did not preserve her, more than her brother, from the satire of Boileau. The pomp and seK- conceit of the brother, and the extreme ugliness of the sister, furnished the poet with abundant topics of ridicule. The earliest romances of Mad. Scudery were published under the name of her brother, and, in fact, he contributed his assistance to these compositions.

At first Madeleine aided her brother in his writing, and perhaps in this way acquired some of the mere formal art of composition, but snb- sequenUy these relations were inverted. Madeleine was in every case the inventor ; she conceived the plan. Both, then, worked out the par- ticulars in conversation. Madeleine penned the narrative, while Georges contributed occasional ideas or military descriptions. His name ap- peared on the title of Ibrahim, Cyrus, and Civile.

The life of the " Vierge des Blkrais," as she was called, was as blame- less as her books. '* Althoueh you have not written your books with an eye to the public/' wrote Mascaron to Mademoiselle Scudery, 'I am pleased with the public for keeping you constantly in view and concerning itself about the employment of a leisure, of which, it seems to me, you owe some account to the whole world. Cyrus, CMlie, and Ibrahim supply my autumn reading. These works have ever the charm of novelty for me, and I discover in them so many things calculated to reform society, that I do not scruple to tell you that you will often find yourself side

It is said, that M. and Mile. Scuddry, travelling together at a time when they were engaged in the composition of Artamenes, arrived at a small inn, where they entered into a discussion, whether they should kill the prince Mazares, one of the characters in that romance, by poison or a dagger ; two merchants who overheard them, procured their arrest, and they were in consequence conducted to the Conciergerie but distuissed after an explanation. A similar story has been somewhere related of Beaumont and Fletcher. While these dramatists were planning the plot of one of their tragedies at a tavern, the former was overheard to say, " I'll xmdertake to kill the king.*' In- formation being given of this apparently treasonable de- sign, they were instantly apprehended, but were dismissed on explaining that they had merely imagined the death of a theatrical monarch.

[piece omitted]

No hero of antiquity has been so much disfigured as Cyrus by romance. Ramsay, we have already seen (vol. ii. p. 348), has painted him as a pedantic politician. The picture represented in the Artamenes, ou Le Grand Cyrus, of Mile. Scudéry, bears still less resemblance to the hero of Herodotus, the sage of Xenophon, or the king announced by the Hebrew prophets. The romance of which the Persian' monarch is the principal character, is the second written by Mile, de Scudery, and, like Ibrahim, passed on

its first publication xmder the name of her brother. It is the longest of all the French heroic romances, and reaches ten octavo volumes and 6,679 pages.

Astyages, king of Media, perplexed by the disastrous horoscope of his grandchild Cjrus, ordered him to be ex- posed on a desert mountain.^ Harpage, however, the officer charged with this errand, committed him to the care of Mitradate, a shepherd, by whom he was reared. He soon distinguished himself among his companions, over whom he exerted a sort of regal authority. By the confession' of the shepherd, it was <£scovered that his foundling is the grandson of Astyages; but the magi being clearly of opinion that the sway he assumed over his companions, was the royal usurpation portended by the planets, Cyrus was sent for to court, and in this portion of the romance, some babyish anecdotes are related in the manner of Xenophon.

The constellations again became malignant, and Cyrus was banished to Persia. From this country he set out on bis travels, bearing the assumed name of Artamenes, and under this appellation visited different towns of Greece, particularly Corinth, where he was ^nagnificently enter- tained by the sage Periander and his mother. On his re- turn to Asia he passed into Cappadocia, over which his uncle Cyaxeres, son of Astyages, then reigned in right of his queen. As this monarch, like his father, was under- stood to have a superstitious terror for Cyrus, the young prince was obliged to appear incognito. It was in a temple ^

^ See table of Aryan Exposure and return Formula No. X. Append, vol. i. The author tells the reader in the advertisement ro vol. v. that she sometimes follows Herodotus and sometimes Xenophon, and the chronology and the personages agree with the Cyropiedaea and the account in Herodotus. The latest translation of Xenophon's work which she could have used was that by Fyramus de Candolle, 1613, while Herodotus was first translated by Dn Kyer in 1 645. — Koertino, p. 420.

' In the heroic novels' temples were very generally the meeting place of friends or lovers, just as, it will be remembered, was the case in the Greek erotic romances, the influence of which is in this as in other features apparent. In the address to the reader prefixed to vol. i. of the Cyrus, the author says : '* i'ay pris et . . . ie prendray tousjours pour mes vniques Modelles Timmortel H6liodore et le Grand Vrf4. Ce sont les senis Maistres que i'imite, et les seuls qn'il faut imiter : car quiconque s'^artera de leur route s'^rera certainement." See vol. i. supp. note, p. 445.

of Sinope, the capital of Cappadocia, that he first beheld Mandane, the daughter of Oyaxares, and heroine of the romance, who came with her father and his magi to return thanks for the demise of Cyrus, who had been belieTed dead since his departure from Persia. Although engaged in this ungracious ofl&ce, Cyrus became deeply enamoured of the princess, or, as the romance expresses it, was amorously blasted by her divine apparition.

Cyrus ^ was thus induced to offer his services to Cyaxares, in the contest in which he was then engaged with the king of Pontus, who had declared war, because he was refused the Princess Mandane in marriage. A soldier of fortune, called Philidaspes, but who afterwards proves to be the king of Assyria, also served in the Cappadocian army. He. too. was in love with Mandane, and between this adventurer and Artamenes there was a perpetual rivalshipof love and glory.

Meanwhile intelligence arrived from old Astyages, that, in order to preclude all chance of the Persian family ever mounting the throne of Media, he had resolved again to marry, and that on reflection, the only suitable alliance appeared to him to V© Thomyris, queen of Scythia. Arta- menes is despatched by Cyaxares on an embassy, to propi- tiate this northern potentate. On his arrival, the queen unfortunately falls in love with him, which defeats the object of his mission, and he with difficulty escapes from her hands. He finds, on returning to Cappadocia, that his rival, the king of Assyria, had succeeded in carrying off Mandane, and had conveyed her to Babylon. Artamenes is placed at the head of the Cappadocian army, and marches against the capital of Assyria. The town is speedily in- vested, but when it is on the point of being captured, the king privately escapes, and, taking Mandane along with

^ Cyrus is the great Cond4, and Mandane Madame de LongueviUe : Cr^sus s= Archduke Leopold ; Feraulas «» M. de Rohan ; Lea Egyptiens ss les Lorrains ; Princess of Salamis ^= Marquise de Sabld, etc. etc The city of Artaxate « Paris, The Siege of Cumaa = siege of Dunkirk, battle of the Massagetae = battle or Rocroy. M. Cousin praises the striking truthfulness of the descriptions of these engagements, etc. A full kev to the work, preserved in the library of the Arsenal, has been printed by V. Cousin, as appendix to torn. i. of his La Society fran^ise au xvii* siecle d*aprds la Grand Cyrus, Paris, 1858. From it we have taken the above few names.

him, shuts himself up in Sinope. Thither Artamenes inarches with his army, but on arriving before its walls, he finds the city a prey to the flames. Artamenes on seeing this, begins to expostulate with bis gods, taxing them in pretty round terms with cruelty and injustice. The cir- cumstances were, no doubt, perplexing, but scarcely such as to justify the absurdity and incoherence manifested in his long declamation. At length, however, he derives much consolation by reflecting, that if he rush amid the flames, his ashes will be mingled with those of his adored princess ; a commixtion which, considering the extent of the confla- gration, was more to be desired than expected. One of his prime counsellors perceiving that he stood in need of advice, now gives it as his opinion, that it would be most expedient to proceed in the very same manner they would do if the town were not on fire. The greater part of the army is accordingly consumed or crushed by the falling houses, but Cyrus himself reaches the tower where he sup- posed Mandane to be confined. Here he discovers the king of Assyria, but Mandane had been carried off in the con- fusion by one of the confidants of that prince. The rivals agree for the present to postpone their difference, and unite to recover Mandane. The subsequent part of the romance is occupied with their pursuit, and their mutual attempts to rescue the princess from her old lover, the king of Pontus, under whose power she had fallen, and who pos- sesses the magic ring of Gyges,^ which rendered its wearer invisible. We have also the history of the jealousy of Mandane, and the letters that pass from the unfortunate Mandane to the unfaithful Cyrus, and from the unhappy Cyrus to the unjust Mandane.

^ Plato (De Rep. 1. ii.) says that Gyges, haring descended into a chasm in the earth, found a brazen horse, and, opening its side, perceired a man's corpse of gigantic statnre, from a finger of which he took a brazen ring, which rendered him, when he put it on, invisible. By its means he entered the apartment of Candaules, King of Lydia, unseen, slew him, usurped his throne, and espoused his widow. Cf. Cicero, De Officiis, 1. iii. c. 4, € 38. Mile. Scud^ry, says Koerting, doubtless derived the myth from Ueliodoms, iv. 8, and viii. 9 (i. p. 27), as did also probably Ariosto (Orl. Fur. c. U^. Cf. Edelealand du M^ril, Floire et Blancenor, ed. 1856, p. clxii. The Tamkappe, of the Nibelungenlied, and fern seed possess a similar virtue.

At lengtli CjTus succeeds in rescuing his mistress from the king of Pontus, and, as the Assyrian monarch was slain in the course of the war, he has no longer a rival to dread : his grandfather and uncle having also laid aside their superstitious terrors, he finally espouses the Princess Mandane at Ecbatana, the capital of Media.*

The episodes in this romance are very numerous, and consist of the stories of those princes who are engaged as auxiliaries on the side of Cyrus or the king of Pontus, This is the romance which has been chiefly ridiculed in Boileau's "Les Heros de Roman." Diogenes addressing Pluto, says, " Diriez vous pourquoi Cyrus a tant conquis de provinces . . . et ravagd plus de la moitie du monde ? " " Belle d^mande ! " replies Plato. " C'est que c'etoit un prince ambitieux. . . . Point du tout ; c'est qu'il vouloit delivrer sa princesse qui avoit ^t^ enlevife. . . . Et savez vous combien elle a dte enlevee de fois ? — Oii veux-tu que je Taille chercher? — Huit fois. — Voila une beautc qui a pass^ par bien des mains."

[Clelia section omitted]

The romance of Almahide,

also by Mad. Scud^ry, is f oimded on the dissensions of the Zegris and Abencerrages (see supra, ii. p. 405, etc.), and opens with an account of a civil broil between these factions in the streets of Granada. The contest was beheld from the summit of a tower, by Eoderic de Narva, a Spanish general, who had been taken prisoner by the Moors, and Fernand de Solis, (a slave of Queen Almahide,) who, at the request of the Christian chief, related to him the his- tory of the court of Granada.

On the birth of Almahide, the reigning queen, an Ara- bian astrologer predicted that she would be happy and unfortunate, at once a maid and a married woman, the wife of a king and a slave, and a variety of similar conim- drums. In order that she might avoid this inconsistent destiny, her father Morayzel sent her to Algiers, under care of the astrologer, who must have been the person of all others most interested in its fulfilment. The expedi- tion falls into the hands of corsairs who scuttle the vessel, and sail off with Almahide to Origni, an isle off the Nor- man coast, where she grows up under the care of Dom

which Voltaire has appreciated. Ci^lie gives us portraits of all the people who made a noise in the world at the date its author lived (Cf. Borrommeo, supra, vol. i., p. 3). . . . Letter from Voltaire to Mmo. Deifant, April 24, 1769.

^ Almahide ou I'esclave reyne par Mde. Scud^ry, Paris, 1660, 8 vols. See Bib. Univ. des Romans, 1775, Aout. pp. 155-214. An English translation, by J. Phillips, London, 1677, fol., and a German b? F. A. Pernauern, Niimberg, 1697.

CH. XII.] ALMAHIDE. 441

Fernand, one of her attendants, who had been captured with her. Subsequently the pirates set sail for Constan- tinople, in order to sell Almahide to the Sultan. They are wrecked on the coast of Andalusia. Dom Fernand is separated from his charge, who was received in the palace of Doih Pedro de Leon, the duke of Medina-Sidonia, where a reciprocal attachment arose between her and Ponce de Leon, son of that nobleman, and she soon after won the affections of the marquis of Montemayor, heir of the duke d'Infantada, having in the meanwhile embraced Christianity.

At length the parents of Almahide, learning that she was in the palace of Medina Sidonia, sent to reclaim her, and she was accordingly delivered up to them. Ponce de Leon followed her to G-ranada, in the garb of a slave : in that disguise he got himself sold to Morayzel, the father of Almahide, who presented him to that lady. A similar stratagem was adopted by her other Spanish lover, who allowed himself to be taken prisoner in a skirmish with the Moors, commanded by Morayzel, who ordered him to be conducted to Granada, and presented likewise as an attendant to his daughter.

The dissensions which arose between the two lovers thus placed around the person of their mistress, are re- strained by the prudence and temper of Almahide, but each watehes in secret an opportunity of supplanting his rival.

Meanwhile Boaudilin, king of Granada, beheld his em- pire a prey to the factions of the Zegris and Abenoerrages. As the monarch was of the former tribe, it was judged advisable, in order to heal the dissensions, that he should chuse a queen from among the latter. Unfortunately he was so deeply enamoured of Miriam, a woman of low birth, whom it would have been unsuitable to have raised to the regal dignity, that he refused to offend her by espousing another. In these circumstances, Almahide was requested to impose on the public, by performing for a season the exterior offices of queen. She readily con- sented to execute a part in this plan ; but she had scarcely entered on the public performance of royalty, when the king fell in love with her pseudo majestv, and unex-

442 HISTORY OF FICTION. [CH. XU.

pectedlj proposed that she should not confine herself to the discharge of the ostensible duties of her situation. This important change in the original stipulation was re- sisted by Almahide, on the ground that her heart was already engaged to another, and the romance breaks off with an account of some ineffectual stratagems, on the part of the king, to discover for whose sake Almahide rejected a more ample participation in the cares of royalty.

It will be perceived that the romance is left incomplete, and the part of which an abstract has been given, though published in eight volumes 8vo., can only be regarded as a sort of introductory chapter to the adventures that were intended to follow.

[omission]

Of the analogies that subsist between all the depart- ments of Belles Lettres, none are more close than ^ose of romance and the drama. Accordingly, as the Italian tales supplied the materials of our earliest tragedies and comedies, so the French heroic romances chiefly contributed to the formation of what may be considered as the second great school of the English drama, in which a stately cere- monial, and uniform grandeur of feeling and expression, were substituted for those grotesque characters and multi- farious passions, which had formerly held possession of the stage. From the French romances were derived the in-

^ Paris, 1667, 1 vol. ; other editions, Villefmnche, 1704 ; the Hague, 1736. Analysed in Koerting, pp. 453-457.

cidents that constitute the plots of those tragedies which appeared in the days of Charles 11. and WilUam, and to them may be attributed the prevalence of that false taste, that pomp and unnatural elevation, which characterize the dramatic productions of Dryden and Lee.

It appears very unaccountable that such romances as those of Calpr^nede and Scud^ry, should in foreign countries have been the object of any species of literary imitation; but in their native soil the popularity of heroic romances, particularly those of Mdlle. de Scudery, may, I think, be in some measure attributed to the number of living characters that were delineated. All were anxious to know what was said of their acquaintance, and to trace out a real or imaginary resemblance. The court ladies were delighted to behold flattering portraits of their beauty in IbnJiim or Olelia, and perhaps fondly hoped that tibeir charms were consecrated to posterity. Hence the fame of the romance was transitory as the beauty, or, at least, as the existence, of the individuals whose persons or characters it pourtrayed. Mankind are little interested in the eyes or eye-brows of antiquated coquettes, and the works in which these were celebrated, soon appeared in that in- trinsic dulness which had received animation from a tem- porary and adventitious interest. This charm being lost, nothing remained but a love so spiritualized, that it bore no resemblance to a real passion, and manners which referred to an ideal world of the creation of the author. The sentiments, too, of chivalry, which had revived imder a more elegant and gallant form during the youth of Louis XIV. had worn out, and their decline was fatal to the works which they had called forth and fostered. The fair sex were now no longer the objects of deification, and those days had disappeared, in which the duke of Eoche- foucault could thus proclaim the influence of the charms of his mistress :

Pour meriter son ccenr pour plaire a ses beaux veux, J'ai fait guerre a mon roi, Je Paurois fait aux Dieux.^

^ The lines are Dn R\-er'8. La Rochefoucault wrote them beneath the portrait of Madame de Long^ueville. See (Euvres de la Comtease de La rajette, etc. Paris, 1804, vol. i., p. vii. — Lisb.

Besides, the size and prolixity of these compositions had a tendency to make them be neglected, when literary works began to abound of a shorter and more lively nature, and when the ladies had no longer leisure to devote the attention of a year and a half to the histoiy of a fair Ethiopian/

^ Mdlle. Scud^rj was also the author of a couple of stories — C^linte, Paris, 1661, pp. 390; and C^lanire, Paris, 1669, 1671, and 1698, pp. 415. The novels of Scud^ry (remarks Koerting, p. 405) like those of Camus, Gromberville, and La Calpren^e, manifest no literary progress or development in their authors, and this phenomenon is a significant characteristic of the whole idealistic school, and an indication that it lacked in general the sprines of fresh pulsating life ; that its writers composed without drawing from the fund of their own intimate expe- riences, feelings, and observation — without projecting into their work their own individuality. Their romances are for the most part like the Greek tales, artificial products of the intellect, elaborated with wonderful niceties of style and composition rather than the genial production of imaginative conception. The first of Scud^ry's books is at least as good aesthetically as any of her later works. This stagnation is in noteworthy contrast to the evolution of the modem English novel by Richardson and Fielding, for instance Clarissa Harlowe could no more have been written before Pamela, than Joseph Andrews before Turn Jones. — EoERTiva, p. 405.

Among the numerous minor authors of the school of idealistic romance are several who may be briefly commemorated before we quit the sub- ject. Fran9ois Sieur de Moliere et d'Essartines (bom about 1600, killed 1623) published in 1620 a collection of stories under the title of ** La Semaine Amoureuse," and subsequently one volume (books i. — iv.) of the half* past oral, half-heroic romance La Polix^ne, or Les Advantures de Polixine (Paris, 1623), dedicated to the Princess Conti. The book was very popular, and a continuation was published in 1632, and another, Vraye Suite des Aduantures de la Polixene . . . suivie et con- clue sur ses Memoires, in 1634. Sorel, who criticizes the work very un- favourably in his Berger Extravagant (I. xiii.), describes it as nothing more or less than an expansion of the Daphnis episode given at the beginning of vol. iii. of the Astrte. Sorel, however, believed he would have achieved better things if he had not, like Audiguier, prematurely met his death at the hand of one he believed his friend. This Audiguier was the author of Lisandre and Caliste, dramatized by Du Ryer in 1632. and Les Amours d'Aristandre et de Cl^onioe, noticed in Sorel's ** Be- marques," p. 495, etc. (See Koerting, pp. 381-384.)

Fran9ois du S^ucy, Sieur de Gerzan (born towards end of sixteenth century )first and most important romance, Histoire Afriquoine de Cl^ mede et de Sophonisbe (Paris, pt. L, 1627, pts. II., III., 162$). De Gernn purposed to write romances, the scenes of which were to be the other three continents ; the heroes he deals with are none other than Scipio, Alex- ander, Charles V., Henry IV., and Louis XIII. , and his narrative is not

In addition to all this, the heroic romance, when verging

to its decline, was attacked by genius almost equal to that

by which the tales of chivalry had formerly been laughed

out of countenance. Molifere's " Pr^cieuses Bidicules "

appeared in 1659, when the heroic romance was too much

in vogue to be easily brought into discredit ; but the satire

of Boileau, entitled Les Heros de Boman, Dialogue, though

written about the same period, was not published till after

the death of Mdlle. Scudery, in 1701, by which time the

reputation of her romances was on the wane, and was

probably still farther shaken by the ridicule of Boileau.

That poet informs us, that in his youth, when these works

were in fashion, he had perused them with much admira-

tion, and regarded them as the master-pieces of the lan-

guage. As his taste, however, improved, he became alive

to their absurdities, and composed the dialogue above-

mentioned, which he declares to be "Le moins frivole

ouvrage qui soit encore sorti de ma plume." In this work

the scene is laid in the dominions of Pluto, who complains

to Minos, that the shades which descend from earth no

longer possess common sense, that they all talk galanterie,

to ofiend *' a chaste and honorable ear." The chief materials of the romance are drawn firom the Amadis and from the Greek erotic romances. The beginning is imitated from Heliodorns, and other features are borrowed from lamblichus and Xenophon, diluted with a liberal amount of alchymical trash, vital elixirs, potable gold, concoctions for making the fair sex fair for ever, etc., much ridiculed by Sorel in his Polyandre, and by Cyrano in Voyage a la Lane. A German translation of the work by *< der Fiirtige,^ t>., Philipp Zesen (1689)— Die Afrikanische Sophonisbe, Frankfurt, sold by Johann David Zunnern, 1674 — was dedi- cated to Queen Christina of Sweden. An analysis of this version is given by Cholevius, p. 29. (See supra, vol. i., p. 20.)

See also

- Mademoiselle Scuderi by Hoffmann

- Les femmes et les salons littéraires

- Salon littéraire

- Préciosité

- Carte de Tendre

- Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus

- The Women of the French Salons (New York, 1891) by Amelia Gere Mason