Madeleine de Scudéry

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 10:25, 25 August 2023 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| | style="text-align: left;" | | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | "[[Jean Chapelain|Chapelain]] and [[Paul Pellisson|Pelisson]] were her friends, as were also the [[Antoine Godeau|Abbé Godeau]] better known as "le Nain de Julie," and [[Madeleine de Scudéry|Madame de Scudery]], ugly, courtly, and clever, the [[Richardson]] of [[romance]] - at least in length."--''[[The Gentleman's Magazine]]'' | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "Her and her brother's heroes never enter an apartment until all the [[furniture]] has been inventoried."--"[[Les héros de roman]]" by Boileau | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "The most voluminous writer of [[heroic romance]] is Mmle de [[Scudery]], whose numerous productions amount to near | ||

| + | fifty volumes."--''[[History of Fiction (John Colin Dunlop)|History of Fiction]]'' (1814) by John Colin Dunlop | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "The [[Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa|whole romance]] is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of [[Boileau]], that when one of [[Madeleine de Scudéry|Mad. Scudery]]'s characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the [[furniture]]."--''[[History of Fiction (John Colin Dunlop)|History of Fiction]]'' (1814) by John Colin Dunlop | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| "She expresses so delicately the most difficult [[feeling]]s to [[express]] and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the [[loving]] [[heart]] … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--[[Madeleine de Scudéry]] describing herself in vol. 10 of ''[[Artamène]]'', using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG | "She expresses so delicately the most difficult [[feeling]]s to [[express]] and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the [[loving]] [[heart]] … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--[[Madeleine de Scudéry]] describing herself in vol. 10 of ''[[Artamène]]'', using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG | ||

| <hr> | <hr> | ||

| Line 6: | Line 15: | ||

| Is not worthy of love. | Is not worthy of love. | ||

| - | --'''''Mademoiselle de Scudéri''''' (1819) is a novella by E. T. A. Hoffmann | + | --''[[Mademoiselle de Scudéri]]'' (1819) is a novella by E. T. A. Hoffmann |

| - | + | <hr> | |

| + | "But what has chiefly excited [[ridicule]] in [[Clelia|this romance]], is the [[Carte du pays de Tendre]] prefixed in the map of this [[imaginary land]], there is laid down the river D'Inclination, on the right bank of which are situated the villages of Jolis vers, and Epitres Galantes; and on the left those of Complaisance, Petits soins and Assiduites. Farther in the country are the cottages of Légereté and Oubli, with the lake Indifference. By one route we are led to the district of Desertion and Perfidie, but by sailing down the stream, we arrive at the towns Tendre sur Estime, Tendre sur Inclination, etc."--''[[History of Fiction (John Colin Dunlop) |History of Fiction]]'' (1814) by Dunlop | ||

| + | |||

| |} | |} | ||

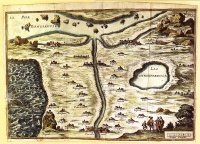

| [[Image:Carte du tendre.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The ''[[Map of Tendre]]'' featured in ''Clélie'']] | [[Image:Carte du tendre.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The ''[[Map of Tendre]]'' featured in ''Clélie'']] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | '''Madeleine de Scudéry''' (1607 – 1701) was a [[French writer]] best known for the novel sequence ''[[Clelie]]'' (1654-1660). | + | '''Madeleine de Scudéry''' (1607 – 1701) was a [[French writer]] best known for the novel sequence ''[[Clélie]]'' (1654-1660). |

| + | ==Overview== | ||

| + | In 1637, following the death of her uncle, Scudéry established herself in Paris with her brother. Georges de Scudéry became a playwright. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Madeleine often used her older brother's name, [[Georges de Scudéry|George]], to publish her works. She was at once admitted to the [[Hôtel de Rambouillet]] coterie of [[précieuses|préciosité]], and afterwards established a [[salon (gathering)|salon]] of her own under the title of the ''Société du samedi'' (''Saturday Society''). | ||

| + | |||

| + | For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of '''Sapho''' or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first [[bluestocking]] of France and of the world. | ||

| - | Her works also demonstrate such comprehensive knowledge of [[ancient history]] that it is suspected she had received instruction in Greek and Latin. In 1637, following the death of her uncle, Scudéry established herself in Paris with her brother. Georges de Scudéry became a playwright. Madeleine often used her older brother's name, [[Georges de Scudéry|George]], to publish her works. She was at once admitted to the [[Hôtel de Rambouillet]] coterie of [[précieuses|préciosité]], and afterwards established a [[salon (gathering)|salon]] of her own under the title of the ''Société du samedi'' (''Saturday Society''). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of '''Sapho''' or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first [[bluestocking]] of France and of the world. She formed a close romantic relationship with [[Paul Pellisson]] which was only ended by his death in 1693. She never married. | + | She formed a close romantic relationship with [[Paul Pellisson]] which was only ended by his death in 1693. She never married. |

| + | Her works demonstrate such comprehensive knowledge of [[ancient history]] that it is presumed she had received instruction in Greek and Latin. | ||

| == Influence == | == Influence == | ||

| The [[romance]]s of Madeleine de Scudéry gained great influence with plots situated in the ancient world and content taken from life. The famous author told stories of her friends in the literary circles of Paris and developed their fates from volume to volume of her serialised production. Readers of taste bought her books, as they offered the finest observation of [[human nature|human motives]], [[psychological realism|characters taken from life]], excellent [[morals]] regarding how [[etiquette|one should and should not behave]] if one wanted to succeed in public life and in the [[gossip|intimate circles she portrayed]]. | The [[romance]]s of Madeleine de Scudéry gained great influence with plots situated in the ancient world and content taken from life. The famous author told stories of her friends in the literary circles of Paris and developed their fates from volume to volume of her serialised production. Readers of taste bought her books, as they offered the finest observation of [[human nature|human motives]], [[psychological realism|characters taken from life]], excellent [[morals]] regarding how [[etiquette|one should and should not behave]] if one wanted to succeed in public life and in the [[gossip|intimate circles she portrayed]]. | ||

| - | ==Comment by Sainte-Beuve== | + | ==Criticism by Sainte-Beuve== |

| In ''[[Portraits Of The Seventeenth Century Historic And Literary]]'' (1909)[https://archive.org/details/portraitsofthese009067mbp] [[Sainte-Beuve]] said that her books are unreadable: | In ''[[Portraits Of The Seventeenth Century Historic And Literary]]'' (1909)[https://archive.org/details/portraitsofthese009067mbp] [[Sainte-Beuve]] said that her books are unreadable: | ||

| Line 42: | Line 60: | ||

| The 19th century German short-story writer [[E.T.A. Hoffmann]] wrote what is usually referred to as the first German-language detective story, featuring Scudéry as the central figure. "[[Madamoiselle de Scuderi|Das Fräulein von Scuderi]]" (Mademoiselle de Scudery) is still widely read today, and is the origin of the "Cardillac syndrome" in psychology. | The 19th century German short-story writer [[E.T.A. Hoffmann]] wrote what is usually referred to as the first German-language detective story, featuring Scudéry as the central figure. "[[Madamoiselle de Scuderi|Das Fräulein von Scuderi]]" (Mademoiselle de Scudery) is still widely read today, and is the origin of the "Cardillac syndrome" in psychology. | ||

| ==Biography== | ==Biography== | ||

| - | Born at [[Le Havre]], [[Normandy]], in northern [[France]], she is said to have been very plain as well as without fortune, but she was very well educated. Establishing herself at [[Paris]] with her brother, she was at once admitted to the [[Hôtel de Rambouillet]] coterie, and afterwards established a [[salon (gathering)|salon]] of her own under the title of the ''Société du samedi'' (''Saturday Society''). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of '''Sapho''' or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first [[bluestocking]] of France and of the world. She formed a close friendship with [[Paul Pellisson]] which was only ended by his death in 1693. | + | Born at [[Le Havre]], [[Normandy]], in northern [[France]], she is said to have been very [[plain]] as well as without fortune, but she was very well educated. Establishing herself at [[Paris]] with her brother, she was at once admitted to the [[Hôtel de Rambouillet]] coterie, and afterwards established a [[salon (gathering)|salon]] of her own under the title of the ''Société du samedi'' (''Saturday Society''). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of '''Sapho''' or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first [[bluestocking]] of France and of the world. She formed a close friendship with [[Paul Pellisson]] which was only ended by his death in 1693. |

| + | |||

| ==Later years== | ==Later years== | ||

| Madeleine survived her brother by more than thirty years, and in her later days published numerous volumes of conversations, to a great extent extracted from her novels, thus forming a kind of anthology of her work. She outlived her vogue to some extent, but retained a circle of friends to whom she was always the "incomparable Sapho." | Madeleine survived her brother by more than thirty years, and in her later days published numerous volumes of conversations, to a great extent extracted from her novels, thus forming a kind of anthology of her work. She outlived her vogue to some extent, but retained a circle of friends to whom she was always the "incomparable Sapho." | ||

| Her ''Life and Correspondence'' was published at Paris by MM. Rathery and Boutron in 1873. | Her ''Life and Correspondence'' was published at Paris by MM. Rathery and Boutron in 1873. | ||

| - | |||

| - | ==Literature== | ||

| - | *[[Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve|Sainte-Beuve]], ''Causeries du lundi,'' volume IV (Paris, 1857-62) | ||

| - | *Rathery and Boutron, ''Mademoiselle de Scudéry: Sa vie et sa correspondance'' (Paris, 1873) | ||

| - | *[[Victor Cousin]], ''La société française au 17ème siècle'' (sixth edition, two volumes, Paris, 1886) | ||

| - | *André Le Breton, ''Le roman au XVIIème siècle'' (Paris, 1890) | ||

| - | *[[Amelia Gere Mason|AG Mason]], ''[[The Women of the French Salons]]'' (New York, 1891) | ||

| - | *Georges Mongrédien, ''Madeleine de Scudéry et son salon: d'après des documents inédits'', 1946 | ||

| - | *Dorothy McDougall, ''Madeleine de Scudéry: her romantic life and death'', 1972 | ||

| - | *Alain Niderst, ''Madeleine de Scudéry, Paul Pellisson et leur monde'', 1976 | ||

| Summaries of the stories and keys to the characters may be found in [[Heinrich Körting]], ''[[Geschichte des französischen Romans im 17ten Jahrhundert]]'' (second edition, Oppeln, 1891). | Summaries of the stories and keys to the characters may be found in [[Heinrich Körting]], ''[[Geschichte des französischen Romans im 17ten Jahrhundert]]'' (second edition, Oppeln, 1891). | ||

| + | |||

| ==Description of her life and work by Dunlop in ''History of Fiction''== | ==Description of her life and work by Dunlop in ''History of Fiction''== | ||

| Line 67: | Line 77: | ||

| 1701, when she was in the ninety-fourth year of her age. | 1701, when she was in the ninety-fourth year of her age. | ||

| - | The Hotel de Rambouillet seems to have been the | + | The [[Hotel de Rambouillet]] seems to have been the |

| nursery in which the first blossoms of her genius were | nursery in which the first blossoms of her genius were | ||

| fostered ; and it must be acknowledged, that if the suc- | fostered ; and it must be acknowledged, that if the suc- | ||

| Line 86: | Line 96: | ||

| The earliest romances of Mad. Scudery were published | The earliest romances of Mad. Scudery were published | ||

| under the name of her brother, and, in fact, he contributed | under the name of her brother, and, in fact, he contributed | ||

| - | his assistance to these compositions.^ | + | his assistance to these compositions. |

| - | ^ At first Madeleine aided her brother in his writing, and perhaps in | + | At first Madeleine aided her brother in his writing, and perhaps in |

| this way acquired some of the mere formal art of composition, but snb- | this way acquired some of the mere formal art of composition, but snb- | ||

| sequenUy these relations were inverted. Madeleine was in every case | sequenUy these relations were inverted. Madeleine was in every case | ||

| Line 94: | Line 104: | ||

| ticulars in conversation. Madeleine penned the narrative, while Georges | ticulars in conversation. Madeleine penned the narrative, while Georges | ||

| contributed occasional ideas or military descriptions. His name ap- | contributed occasional ideas or military descriptions. His name ap- | ||

| - | peared on the title of Ibrahim, C^rus, and Civile. | + | peared on the title of Ibrahim, Cyrus, and Civile. |

| - | The life of the " Vierge des Blkrais," as she was called, was as blame- | + | The life of the " Vierge des Marais," as she was called, was as blameless as her books. "Although you have not written your books with an eye to the public" wrote [[Mascaron]] to Mademoiselle Scudery, 'I am pleased with the public for keeping you constantly in view and concerning itself about the employment of a leisure, of which, it seems to me, you |

| - | less as her books. '* Althoueh you tuive not written your books with an | + | owe some account to the whole world. Cyrus, Clélie, and Ibrahim supply |

| - | eye to the public/' wrote Mascaron to Mademoiselle Scudery, '* I am | + | |

| - | pleased with the public for keeping you constantly in view and concerning | + | |

| - | itself about the employment of a leisure, of which, it seems to me, you | + | |

| - | owe some account to the whole world. Cyrus, CMlie, and Ibrahim supply | + | |

| my autumn reading. These works have ever the charm of novelty for | my autumn reading. These works have ever the charm of novelty for | ||

| me, and I discover in them so many things calculated to reform society, | me, and I discover in them so many things calculated to reform society, | ||

| that I do not scruple to tell you that you will often find yourself side | that I do not scruple to tell you that you will often find yourself side | ||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | |||

| - | 430 HISTOET OF FICTION. [CH. XII. | ||

| It is said, that M. and Mile. Scuddry, travelling together | It is said, that M. and Mile. Scuddry, travelling together | ||

| Line 117: | Line 119: | ||

| dagger ; two merchants who overheard them, procured | dagger ; two merchants who overheard them, procured | ||

| their arrest, and they were in consequence conducted to | their arrest, and they were in consequence conducted to | ||

| - | the Co7iciergerie but distuissed after an explanation. A | + | the ''Conciergerie'' but dismissed after an explanation. A |

| - | similar story has been somewhere related of Beaumont | + | similar story has been somewhere related of [[Beaumont and Fletcher]]. While these dramatists were planning the |

| - | and Fletcher. While these dramatists were planning the | + | |

| plot of one of their tragedies at a tavern, the former was | plot of one of their tragedies at a tavern, the former was | ||

| overheard to say, " I'll xmdertake to kill the king.*' In- | overheard to say, " I'll xmdertake to kill the king.*' In- | ||

| Line 127: | Line 128: | ||

| a theatrical monarch. | a theatrical monarch. | ||

| - | Ibbahim, ou L'Illusteb Bassa, | + | [section omitted] |

| - | first published in 1635.^ The hero of this romance was | + | [section omitted] |

| - | grand vizier to Solyman the Magnificent. In his youth | + | |

| - | he had been enamoured of the princess of Monaco, but. | + | |

| - | overwhelmed with grief by a false report of her infidelity, | + | |

| - | by side with St. Augustine and St. Bernard, in the sermons which I am | + | [section omitted] |

| - | preparing for the Court." In Cl^lie the author has treated of all that per- | + | |

| - | tains to the condition of women in the world, and we find there under a | + | |

| - | more dispassionate form all the stormy discussions which have arisen in our | + | |

| - | day respecting the freedom of the [[fair sex]] (see [[Fournel]], [[La Littérature Indépendante]], etc., p. 166, quoted by [[Koerting]], p. 400). Strong passion | + | |

| - | is not found in her works, which seem to offer a fair reflex of her | + | |

| - | experience and feelings, and it is improbable that she was erer deeply | + | |

| - | under the influence of love. A portrait of Mile, de Scudéry has been | + | |

| - | drawn by her brother in the character Sapho, in Le Grand Cyrus. | + | |

| - | Mile, de Scud^ry wrote numerous poems. Her verses, says Segrais | + | Of the analogies that subsist between all the departments of [[Belles Lettres]], none are more close than those |

| - | (p. 51), are "assez coulans, et 11 y a toujours quelque pens^ : elle ne | + | |

| - | m'^crit guere tju'elle n'en mele quelques-uns dans ses lettres.^ Victor | + | |

| - | Cousin endorses this opinion. Some of her poems are contained in Mile, | + | |

| - | de Scudery, sa vie, sa Correspondance, avec un choix de ses po&ie:$, | + | |

| - | 1873. See Koerting. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | * 1635 is the date given by Segrais (p. 117) ; but the earliest edition | + | |

| - | known to bibliographers seems to be tiiat of 1641. The work was re- | + | |

| - | published in 1652, 1665,' 1723. Englished by Henry Cogan, London, | + | |

| - | 1652, fol. ; German, by Philipp Zesen, Der Fartige, 1645 ; Ital., Venice, | + | |

| - | 1684. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | CH. XII.] IBBAHIM, OV l'iLLUSTBE BASSA. 431, [see ''[[Ibrahim ou l'Illustre Bassa]]''] | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | he had abandoned Q«noa, his native country, and having | + | |

| - | travelled through Grermany, embarked on the Baltic Sea | + | |

| - | to seek an honourable death in the wars of Sweden. This | + | |

| - | design met with an interruption which no one could have | + | |

| - | anticipated — he was captured by the Dey of Algiers, who | + | |

| - | happened to be cruizing in the Baltic in person ! In re- | + | |

| - | compense, however, of this disaster, his subsequent good | + | |

| - | fortune was equally improbable ; for having been sold as | + | |

| - | a slave at Constantinople, and condemned to death on | + | |

| - | account of an attempt to recover his freedom, the daughter | + | |

| - | of Solyman happened to be at her window to witness the | + | |

| - | execution, and being struck with the appearance of the | + | |

| - | l>risoner, not only procured his pardon, but introduced him | + | |

| - | to her father, who, after conversing a long while on painting, | + | |

| - | mathematics, and music, appointed him Grand Vizier. In | + | |

| - | this capacity he vanquished the Sophy or Shah of Persia, | + | |

| - | and made prodigious havoc among the rebellious Calenders | + | |

| - | of Natolia. At length, however, having learned that the | + | |

| - | rumour concerning the inconstancy of the princess was | + | |

| - | without foundation, he returned to Italy, and offered the | + | |

| - | proper apologies to his mistress; but, as he had only a | + | |

| - | short leave of absence, he again repaired to Constantinople. | + | |

| - | Thither he is shortly afterwards followed by the princess, | + | |

| - | of whom Solyman at first sight becomes so deeply ena- | + | |

| - | moured, that soon after her arrival, the alternative is pro- | + | |

| - | posed to her of witnessing the execution of Ibrahim, or | + | |

| - | complying with the desires of the sultan. In this di- | + | |

| - | lemma, the lovers secretly hire a vessel and sail from | + | |

| - | Constantinople. Their flight, however, is speedily dis- | + | |

| - | covered ; they are pursued, overtaken, and brought back. | + | |

| - | The sultan now resolves to inflict both the punishments of | + | |

| - | which he had formerly left an option : the princess is con- | + | |

| - | demned to the seraglio, and Ibrahim receives a visit from | + | |

| - | the mutes. Suddenly, however, Solyman recollects having | + | |

| - | on some occasion sworn that, during his life and reign, | + | |

| - | Ibrahim should not suffer a violent death. On this point | + | |

| - | of conscience the Grand Seignior consults the mufti, who | + | |

| - | being a man plein d^ esprit et de finesse, as it is said in the | + | |

| - | romance, suggests, that as sleep is a species of death, the | + | |

| - | grand vizier might be strangled without scruple duidng | + | |

| - | the slumbers of the sultan. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | At an early period of the evening, Solyman went to bed | + | |

| - | with a fixed design of falling asleep, but spite of all his | + | |

| - | efforts he continued 'Wakeful during the whole night, and, | + | |

| - | having thus time for reflection, he began to suspect that | + | |

| - | the mufti's interpretation of his oath was less sound than | + | |

| - | ingenious. The lovers were accordingly pardoned, and a | + | |

| - | few days after were shipped off for Genoa, loaded with | + | |

| - | presents from the emperor. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Nothing can be more ridiculous than the conclusion of this romance, particularly the decision of the mufti, and the somniferous attempts of his master. The sudden revolution, too, in the mind of the latter, by which alone the lovers are saved, is produced by no adequate cause, and is neither natural nor ingenious. The whole romance is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of Boileau, that when one of Mad. Scudery's characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the [[furniture]]. An English tragedy, entitled ''[[Ibrahim, or the Illustrious Bassa]]'', is founded on this romance. It was written by Elkanah Settle, and printed in 1677.^ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | No hero of antiquity has been so much disfigured as Cyrus by romance. Ramsay, we have already seen (vol. ii. p. 348), has painted him as a pedantic politician. The picture represented in the Artamenes, ou Le Grand Cyrus, of Mile. Scudéry, bears still less resemblance to the hero of Herodotus, the sage of Xenophon, or the king announced by the Hebrew prophets. The romance of which the Persian' monarch is the principal character, is the second written by Mile, de Scudery, and, like Ibrahim, passed on | + | |

| - | its first publication xmder the name of her brother. It is | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | *^ The main fable of Ibrahim was dramatized by Georges de Scnd^y | + | |

| - | in 1643 ; his tragedy, Axiane, is also drawn from the novel, and the | + | |

| - | episode of Mnstapha and Geangir has been used by Magret and Belin. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Paris, 1649-53; subsequent editions, Paris, 1654, 1656, 165S; | + | |

| - | Leyde, 1655, 1656. Louandre states that the book brought a net profit | + | |

| - | of 100,000 dcus to the publisher, A. Courb^. (Koerting, p. 409.) Ad | + | |

| - | English translation, London, 1653, fol. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | the longest of all the French heroic romances, and reaches ten octavo volumes and 6,679 pages. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Astyages, king of Media, perplexed by the disastrous | + | |

| - | horoscope of his grandchild Cjrus, ordered him to be ex- | + | |

| - | posed on a desert mountain.^ Harpage, however, the officer | + | |

| - | charged with this errand, committed him to the care of | + | |

| - | Mitradate, a shepherd, by whom he was reared. He soon | + | |

| - | distinguished himself among his companions, over whom | + | |

| - | he exerted a sort of regal authority. By the confession' of | + | |

| - | the shepherd, it was <£scovered that his foundling is the | + | |

| - | grandson of Astyages; but the magi being clearly of | + | |

| - | opinion that the sway he assumed over his companions, | + | |

| - | was the royal usurpation portended by the planets, Cyrus | + | |

| - | was sent for to court, and in this portion of the romance, | + | |

| - | some babyish anecdotes are related in the manner of | + | |

| - | Xenophon. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The constellations again became malignant, and Cyrus | + | |

| - | was banished to Persia. From this country he set out on | + | |

| - | bis travels, bearing the assumed name of Artamenes, and | + | |

| - | under this appellation visited different towns of Greece, | + | |

| - | particularly Corinth, where he was ^nagnificently enter- | + | |

| - | tained by the sage Periander and his mother. On his re- | + | |

| - | turn to Asia he passed into Cappadocia, over which his | + | |

| - | uncle Cyaxeres, son of Astyages, then reigned in right of | + | |

| - | his queen. As this monarch, like his father, was under- | + | |

| - | stood to have a superstitious terror for Cyrus, the young | + | |

| - | prince was obliged to appear incognito. It was in a temple ^ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ See table of Aryan Exposure and return Formula No. X. Append, | + | |

| - | vol. i. The author tells the reader in the advertisement ro vol. v. that | + | |

| - | she sometimes follows Herodotus and sometimes Xenophon, and the | + | |

| - | chronology and the personages agree with the Cyropiedaea and the | + | |

| - | account in Herodotus. The latest translation of Xenophon's work which | + | |

| - | she could have used was that by Fyramus de Candolle, 1613, while | + | |

| - | Herodotus was first translated by Dn Kyer in 1 645. — Koertino, p. 420. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ' In the heroic novels' temples were very generally the meeting place | + | |

| - | of friends or lovers, just as, it will be remembered, was the case in the | + | |

| - | Greek erotic romances, the influence of which is in this as in other | + | |

| - | features apparent. In the address to the reader prefixed to vol. i. of the | + | |

| - | Cyrus, the author says : '* i'ay pris et . . . ie prendray tousjours pour | + | |

| - | mes vniques Modelles Timmortel H6liodore et le Grand Vrf4. Ce sont | + | |

| - | les senis Maistres que i'imite, et les seuls qn'il faut imiter : car quiconque | + | |

| - | s'^artera de leur route s'^rera certainement." See vol. i. supp. | + | |

| - | note, p. 445. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | IT. F P | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 434 HISTORY OP FICTION. [CH. XII. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | of Sinope, the capital of Cappadocia, that he first beheld | + | |

| - | Mandane, the daughter of Oyaxares, and heroine of the | + | |

| - | romance, who came with her father and his magi to return | + | |

| - | thanks for the demise of Cyrus, who had been belieTed | + | |

| - | dead since his departure from Persia. Although engaged | + | |

| - | in this ungracious ofl&ce, Cyrus became deeply enamoured | + | |

| - | of the princess, or, as the romance expresses it, was | + | |

| - | amorously blasted by her divine apparition. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Cyrus ^ was thus induced to offer his services to Cyaxares, | + | |

| - | in the contest in which he was then engaged with the king | + | |

| - | of Pontus, who had declared war, because he was refused the | + | |

| - | Princess Mandane in marriage. A soldier of fortune, called | + | |

| - | Philidaspes, but who afterwards proves to be the king of | + | |

| - | Assyria, also served in the Cappadocian army. He. too. | + | |

| - | was in love with Mandane, and between this adventurer and | + | |

| - | Artamenes there was a perpetual rivalshipof love and glory. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Meanwhile intelligence arrived from old Astyages, that, | + | |

| - | in order to preclude all chance of the Persian family ever | + | |

| - | mounting the throne of Media, he had resolved again to | + | |

| - | marry, and that on reflection, the only suitable alliance | + | |

| - | appeared to him to V© Thomyris, queen of Scythia. Arta- | + | |

| - | menes is despatched by Cyaxares on an embassy, to propi- | + | |

| - | tiate this northern potentate. On his arrival, the queen | + | |

| - | unfortunately falls in love with him, which defeats the | + | |

| - | object of his mission, and he with difficulty escapes from | + | |

| - | her hands. He finds, on returning to Cappadocia, that his | + | |

| - | rival, the king of Assyria, had succeeded in carrying off | + | |

| - | Mandane, and had conveyed her to Babylon. Artamenes | + | |

| - | is placed at the head of the Cappadocian army, and marches | + | |

| - | against the capital of Assyria. The town is speedily in- | + | |

| - | vested, but when it is on the point of being captured, the | + | |

| - | king privately escapes, and, taking Mandane along with | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Cyrus is the great Cond4, and Mandane Madame de LongueviUe : | + | |

| - | Cr^sus s= Archduke Leopold ; Feraulas «» M. de Rohan ; Lea Egyptiens | + | |

| - | ss les Lorrains ; Princess of Salamis ^= Marquise de Sabld, etc. etc The | + | |

| - | city of Artaxate « Paris, The Siege of Cumaa = siege of Dunkirk, | + | |

| - | battle of the Massagetae = battle or Rocroy. M. Cousin praises the | + | |

| - | striking truthfulness of the descriptions of these engagements, etc. A | + | |

| - | full kev to the work, preserved in the library of the Arsenal, has been | + | |

| - | printed by V. Cousin, as appendix to torn. i. of his La Society fran^ise | + | |

| - | au xvii* siecle d*aprds la Grand Cyrus, Paris, 1858. From it we have | + | |

| - | taken the above few names. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | GH. XII.] ASTAMENE, OV LE OBAND GYBUS. 435 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | him, shuts himself up in Sinope. Thither Artamenes | + | |

| - | inarches with his army, but on arriving before its walls, he | + | |

| - | finds the city a prey to the flames. Artamenes on seeing | + | |

| - | this, begins to expostulate with bis gods, taxing them in | + | |

| - | pretty round terms with cruelty and injustice. The cir- | + | |

| - | cumstances were, no doubt, perplexing, but scarcely such | + | |

| - | as to justify the absurdity and incoherence manifested in | + | |

| - | his long declamation. At length, however, he derives much | + | |

| - | consolation by reflecting, that if he rush amid the flames, | + | |

| - | his ashes will be mingled with those of his adored princess ; | + | |

| - | a commixtion which, considering the extent of the confla- | + | |

| - | gration, was more to be desired than expected. One of his | + | |

| - | prime counsellors perceiving that he stood in need of | + | |

| - | advice, now gives it as his opinion, that it would be most | + | |

| - | expedient to proceed in the very same manner they would | + | |

| - | do if the town were not on fire. The greater part of the | + | |

| - | army is accordingly consumed or crushed by the falling | + | |

| - | houses, but Cyrus himself reaches the tower where he sup- | + | |

| - | posed Mandane to be confined. Here he discovers the king | + | |

| - | of Assyria, but Mandane had been carried off in the con- | + | |

| - | fusion by one of the confidants of that prince. The rivals | + | |

| - | agree for the present to postpone their difference, and unite | + | |

| - | to recover Mandane. The subsequent part of the romance | + | |

| - | is occupied with their pursuit, and their mutual attempts | + | |

| - | to rescue the princess from her old lover, the king of | + | |

| - | Pontus, under whose power she had fallen, and who pos- | + | |

| - | sesses the magic ring of Gyges,^ which rendered its wearer | + | |

| - | invisible. We have also the history of the jealousy of | + | |

| - | Mandane, and the letters that pass from the unfortunate | + | |

| - | Mandane to the unfaithful Cyrus, and from the unhappy | + | |

| - | Cyrus to the unjust Mandane. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Plato (De Rep. 1. ii.) says that Gyges, haring descended into a | + | |

| - | chasm in the earth, found a brazen horse, and, opening its side, perceired | + | |

| - | a man's corpse of gigantic statnre, from a finger of which he took a | + | |

| - | brazen ring, which rendered him, when he put it on, invisible. By its | + | |

| - | means he entered the apartment of Candaules, King of Lydia, unseen, | + | |

| - | slew him, usurped his throne, and espoused his widow. Cf. Cicero, | + | |

| - | De Officiis, 1. iii. c. 4, € 38. Mile. Scud^ry, says Koerting, doubtless | + | |

| - | derived the myth from Ueliodoms, iv. 8, and viii. 9 (i. p. 27), as did also | + | |

| - | probably Ariosto (Orl. Fur. c. U^. Cf. Edelealand du M^ril, Floire et | + | |

| - | Blancenor, ed. 1856, p. clxii. The Tamkappe, of the Nibelungenlied, | + | |

| - | and fern seed possess a similar virtue. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 436 HISTOET OF FICTION. [CH. XXL | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | At lengtli CjTus succeeds in rescuing his mistress from | + | |

| - | the king of Pontus, and, as the Assyrian monarch was | + | |

| - | slain in the course of the war, he has no longer a rival to | + | |

| - | dread : his grandfather and uncle having also laid aside | + | |

| - | their superstitious terrors, he finally espouses the Princess | + | |

| - | Mandane at Ecbatana, the capital of Media.* | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The episodes in this romance are very numerous, and | + | |

| - | consist of the stories of those princes who are engaged as | + | |

| - | auxiliaries on the side of Cyrus or the king of Pontus, | + | |

| - | This is the romance which has been chiefly ridiculed in | + | |

| - | Boileau's " Les Heros de Roman." Diogenes addressing | + | |

| - | Pluto, says, " Diriez vous pourquoi Cyrus a tant conquis de | + | |

| - | provinces . . . et ravagd plus de la moitie du monde ? " | + | |

| - | " Belle d^mande ! " replies Plato. " C'est que c'etoit un | + | |

| - | prince ambitieux. . . . Point du tout ; c'est qu'il vouloit | + | |

| - | delivrer sa princesse qui avoit ^t^ enlevife. . . . Et savez | + | |

| - | vous combien elle a dte enlevee de fois ? — Oii veux-tu que | + | |

| - | je Taille chercher? — Huit fois. — Voila une beautc qui a | + | |

| - | pass^ par bien des mains." | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | Clelie, ou Hibtoibe Eomaine,^ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | is a romance also written by Mile. Scud^ry, though it was | + | |

| - | originally published under the name of her brother, and | + | |

| - | began to appear a year before the completion of the pre- | + | |

| - | ceding, It consists of ten volumes 8vo, of about eight | + | |

| - | hundred pages each, and was printed at Paris in 1656- | + | |

| - | 1660, and again in 1666 and 1731. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ A fuller analysis of this romance will be found in Koerting, pp. | + | |

| - | 410-420. It is difficult in these times of ^Mife at high pressure*' to | + | |

| - | realize the favour which this long and tedious production enjoyed. S<)me | + | |

| - | explanation is, however, afforded by a passage in Mme. de Genlis* ** De | + | |

| - | rinfluence des femmes sur la litt^rature fran^aise (Paris, 1811, i. p. 126). | + | |

| - | Women led a stereotyped and sedentary kind of life. Instead of singing, | + | |

| - | playing, and getting up concerts, they spent a great portion of the day | + | |

| - | at the embroidery frame, plying their needle in embroidery or tapestry, | + | |

| - | while one of the company read aloud. ... It was the most natural thing | + | |

| - | in the world for them to renew the upholstery of mansion or castle, and | + | |

| - | there was no desire to be short of reading during these lengthy tasks. | + | |

| - | Those eternal conversations in the works of Mademoiselle de ocudery | + | |

| - | which suspend the progress of the story and appear to us so unwar- | + | |

| - | rantably irrevelant, were by no means unwelcome. — Kobbtihg, p. 410. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | * Translated by John Davies, Lond. 1656-61, and 1678, folio. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | CH. XII.] CL^LIE, OV HI8TOIBE BOMAINE. 437 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | This work enjoyed for some time considerable reputation, | + | |

| - | but has finally acquired, and perhaps has deserved, the | + | |

| - | character of being the most tiresome of all the tedious pro- | + | |

| - | ductions of its author. It comprehends fewer incidents | + | |

| - | than the others, and more detail relating to the heart, and | + | |

| - | is filled with those far-fetched sentiments so much in fashion | + | |

| - | in the early age of Lewis XIV. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | But what has chiefly excited ridicule in this romance, is | + | |

| - | the Carte du pays de Tendre * prefixed : in the map of this | + | |

| - | imaginary land, there is laid down the river D'Inclination, | + | |

| - | on the right bank of which are situated the villages of | + | |

| - | Jolis vers, and Epitres Gkilantes ; and on the left those of | + | |

| - | Complaisance, Petits soins and Assiduites. Farther in the | + | |

| - | country are the cottages of Lcgeret^ and Oubli, with the | + | |

| - | lake Indifference. By one route we are led to the district | + | |

| - | of Desertion and Perfidie, but by sailing down the stream, | + | |

| - | we arrive at the towns Tendre sur Estime, Tendre sur In- | + | |

| - | clination, etc. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The action of this romance is placed in the early ages of | + | |

| - | fioman history, and the heroine is that Olelia who escaped | + | |

| - | from the power of Porsenna, by swimming across the | + | |

| - | Tiber. Aronce, the son of that monarch, is the favoured | + | |

| - | lover of Clelia, and his rivals are a young Roman, called | + | |

| - | Horace, King Tarquin, and his son Sextus. A great part | + | |

| - | of the romance is occupied with an account of the expul- | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ This map was the idea of Cbapelain, and may hare been developed | + | |

| - | in the conTeraation of the Saturday reunions, ^ee Cousin, La Soci6t6, | + | |

| - | etc. ii. 280. There were several imitations of this map, e.g, the Histoire | + | |

| - | da Temps ou Kelation du Royaume de la Coqueterie, by the Abb^ | + | |

| - | d'Aubignac, Paris, 1654 ; Carte de la Poesie, in the Mercure Galante | + | |

| - | of Jan. 1672 ; Carte du Pays de la Bragnerie, in Bussy-Rabutin's | + | |

| - | '* Histoire Amoureuse des Gaules," Paris, 1665, and others mentioned | + | |

| - | in Ix>uandre*s *' Conteurs fran9ais Contemporains de Lafontaine," p. 65. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | More interesting and of some historical worth is the account which | + | |

| - | occupies sixty pages or thereabouts of vol. x. of the Palace of Valterre, | + | |

| - | which is really, according to the Bibl. des Rom. a description of the | + | |

| - | sumptpous chtiteau of Vaux-Ia-Vicomte, near Melun, on the banks of | + | |

| - | the Seine, built by the Financier Fouquet ; the g^ardens and building | + | |

| - | were commenced in 1653. Lafontaine also describes this magnificent | + | |

| - | palace in his Songe de Yaux (1615-1680). Eoerting, p. 440. Voltaire, | + | |

| - | too. notes in a letter to Madame Deffant of April 24, 1769, that ** le | + | |

| - | Chateau de Villars, qui appartient anjourd'hui k M. le due de Pralin, y | + | |

| - | est d^crit avec la plus grande exactitude." | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 438 HISTORY OP FICTION. [CH. XII, | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | sion of the royal house, and the siege of Eome under- | + | |

| - | taken by the exiled family and their allies. During the | + | |

| - | continuance of the siege, Clelia resided in a secure place | + | |

| - | in the vicinity of the town, along with other Boman | + | |

| - | ladies, whose society was greatly enliyened by the arrival | + | |

| - | of Anacreon, who was escorting two ladies on their way | + | |

| - | to consult the oracle of Praeneste: though upwards of | + | |

| - | sixty years of age, the Greek poet . was still gay and | + | |

| - | agreeable, and entertained the party as much by his | + | |

| - | conversation^ as his Jolts vers. The romance terminates | + | |

| - | with the conclusion of a separate peace between the | + | |

| - | Eomans and Porsenna, and the union of Clelia with his | + | |

| - | son Aronce.^ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | It is but a small part of the romance, however, which is | + | |

| - | occupied with what is meant as the principal subject ; the | + | |

| - | great proportion of these cumbrous volumes is filled with | + | |

| - | episodes, which are for the most part love-stories, tedious, | + | |

| - | uninteresting, and involved. It is well known, that in the | + | |

| - | characters introduced in these, Mad. de Scud^ry has at- | + | |

| - | tempted to delineate many of her contemporaries. Ac- | + | |

| - | cordingly Brutus has been represented as a spark, and | + | |

| - | Lucretia as a coquette. One of the earliest episodes is | + | |

| - | that of Brutus and Lucretia, who carry on a sentimental | + | |

| - | intrigue, in the course of which Brutus addresses many | + | |

| - | love verses to his mistress, among which are the following ; | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Should a history of conversation in France ever be written, observes | + | |

| - | Foumel (Litt. Ind6p. p. 171), Mile, de Scudery's romances would be en- | + | |

| - | titled to the first place among the materials to be consulted for the | + | |

| - | seventeenth century ; merits and defects are there presented as from the | + | |

| - | life. Mile, de Scud^ry was one of those whose sovereignty in this | + | |

| - | domain was incontestable. She possessed " la passion de la conversation/' | + | |

| - | and bad, says Victor Cousin, an extraordinary talent for carrying on | + | |

| - | dialogues replete with wit and taste. Her romances, indeed, may be | + | |

| - | regarded as spun out conversations, and the romantic incidents merely | + | |

| - | serve as points of connection or a framework for their production ; and | + | |

| - | V. Cousin considers, as the most meritorious work of the author, the | + | |

| - | Conversations, drawn from her novels, which she published separately, | + | |

| - | viz.: Conversations sur divers Sujets, Paris, 1680; Conversations | + | |

| - | nouvelles sur divers sujets, Paris, 1684, Amstenl. 1682; Conversatinns | + | |

| - | Morales, Paris, 1686 ; Nouvelles Conversations de Morale, Paris, 1688 ; | + | |

| - | Entretiens de Morale, Paris, 1 692. See Koerting, p. 402, etc. and supra, | + | |

| - | 267. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ' A fuller analysis in Bibl. Univ. des Rom. 1777, Oct ii. p. 5, etc.; | + | |

| - | and Koerting, pp. 422. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | J | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | CH. XII.] CL^LIE, OU HISTOIBE BOMAINE. 439 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Quand verrai Je ce que J'adore | + | |

| - | Eclairer ces aimables lieux ; | + | |

| - | O doux moraens — momens precieax, | + | |

| - | Ne reviendrez vous point encore — | + | |

| - | Helas ! de I'une a Pautre Aurore, | + | |

| - | A peine ai Je ferm^ les yeux, etc. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | But, if in this masquerade we cannot discover the age of | + | |

| - | Tarquin, we receive some knowledge concerning the man- | + | |

| - | ners and characters of that of Mad. de Scuderj. In the | + | |

| - | fraternity of wise Sjrracusans she has painted the gentlemen | + | |

| - | of Port Bojal, and particularly under the name of | + | |

| - | Tunanto, has exhibited M. Arnauld d'Andilly, one of the | + | |

| - | chief ornaments of that learned society. Alcandre is | + | |

| - | Louis XIV., then only about eighteen years of age, of | + | |

| - | whom she has drawn a flattering portrait. Scaiuns and | + | |

| - | Liriane, who come to consult the oracle of Prsaneste, are | + | |

| - | intended for the celebrated Monsieur, and still more cele- | + | |

| - | brated Madame Scarron, afterwards de Maintenon. In | + | |

| - | Damo, the daughter of Pythagoras, who undertook the | + | |

| - | education of Brutus, she has painted Ninon L'Enclos, who | + | |

| - | instructed in gallantry the young noblemen who fre- | + | |

| - | quented her brilliant society. Finally, she has described | + | |

| - | herself in the portrait ^ of Arricidie, who delighted more | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Free from egotism or over-estimation. (Koerting.) In allusion to | + | |

| - | these disguised portraits of contemporaries, Boileau says in a letter to | + | |

| - | Brossette of January 7, 1703 : " It is alleged that there is not a single | + | |

| - | Roman, man or woman, in this book but is moulded upon the character | + | |

| - | of some townsman or townswoman of the author's quarter. A key was | + | |

| - | circulated at one time, but I never troubled to get it. All I know is | + | |

| - | that the generous Herminius was meant for Pellisson, the agreeable | + | |

| - | Scaurus for Scarron, the gallant Amilcar for Sarrazin, etc. The editor | + | |

| - | of the Bibliotheque Universelle des Romans also mentions (vol. ii. p. 196, | + | |

| - | Oct. 1777) la Clef manuscrite de Cl^lie que nous poss^ons. There are | + | |

| - | no fewer than three hundred and seventy fifl^res in the Romance, and | + | |

| - | there seems little doubt that all or nearly all were intended portraits, | + | |

| - | readily recognizable by contemporaries, a circumstance which doubtless | + | |

| - | gave these long-winded novels an interest which they cannot possess for | + | |

| - | us. In addition to those already mentioned CMlie is Mile, de Longueville, | + | |

| - | and Cl^nime, Fouquet. Notwithstanding the pedantic ridiculousness | + | |

| - | of it9 sentimental metaphysics, writes M. Godefroy, C161ie is worth | + | |

| - | study as a serious and curious book, dealing in a spirited and judicious | + | |

| - | way with all the questions concerning the condition of women in the | + | |

| - | world (see supra, p. 439), the rank allotted them by modem civilization, | + | |

| - | and the preservation of that rank entailed on them. The portraits and | + | |

| - | descriptions, which are objects of Boileau's mockery, have their value, | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 440 HI8T0BT OF FICTION. [CH. XII. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | by the beauties of her mind than by the charms of her | + | |

| - | person. This incon^uous plan of taking personages from | + | |

| - | ancient history, and attributing to them maimers and sen- | + | |

| - | timents of modem refinement, especially with regard to | + | |

| - | the passion of love, is repeatedly censured and ridiculed | + | |

| - | by Boileau in his Art Poetique : — | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | GardeE done le donner, ainsi que dans Clelie, | + | |

| - | L'air et Tesprit Francois a I'antique Italic ; | + | |

| - | Et sous des noms Romains faisant notre portrait, | + | |

| - | l^eindrc Caton galant et Brutus dameret. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The romance of | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Almahide,^ | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | also by Mad. Scud^ry, is f oimded on the dissensions of the | + | |

| - | Zegris and Abencerrages (see supra, ii. p. 405, etc.), and | + | |

| - | opens with an account of a civil broil between these factions | + | |

| - | in the streets of Granada. The contest was beheld from | + | |

| - | the summit of a tower, by Eoderic de Narva, a Spanish | + | |

| - | general, who had been taken prisoner by the Moors, and | + | |

| - | Fernand de Solis, (a slave of Queen Almahide,) who, at | + | |

| - | the request of the Christian chief, related to him the his- | + | |

| - | tory of the court of Granada. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | On the birth of Almahide, the reigning queen, an Ara- | + | |

| - | bian astrologer predicted that she would be happy and | + | |

| - | unfortunate, at once a maid and a married woman, the | + | |

| - | wife of a king and a slave, and a variety of similar conim- | + | |

| - | drums. In order that she might avoid this inconsistent | + | |

| - | destiny, her father Morayzel sent her to Algiers, under | + | |

| - | care of the astrologer, who must have been the person of | + | |

| - | all others most interested in its fulfilment. The expedi- | + | |

| - | tion falls into the hands of corsairs who scuttle the vessel, | + | |

| - | and sail off with Almahide to Origni, an isle off the Nor- | + | |

| - | man coast, where she grows up under the care of Dom | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | which Voltaire has appreciated. Ci^lie gives us portraits of all the | + | |

| - | people who made a noise in the world at the date its author lived | + | |

| - | (Cf. Borrommeo, supra, vol. i., p. 3). . . . Letter from Voltaire to Mmo. | + | |

| - | Deifant, April 24, 1769. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Almahide ou I'esclave reyne par Mde. Scud^ry, Paris, 1660, 8 vols. | + | |

| - | See Bib. Univ. des Romans, 1775, Aout. pp. 155-214. An English | + | |

| - | translation, by J. Phillips, London, 1677, fol., and a German b? | + | |

| - | F. A. Pernauern, Niimberg, 1697. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | CH. XII.] ALMAHIDE. 441 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Fernand, one of her attendants, who had been captured | + | |

| - | with her. Subsequently the pirates set sail for Constan- | + | |

| - | tinople, in order to sell Almahide to the Sultan. They | + | |

| - | are wrecked on the coast of Andalusia. Dom Fernand is | + | |

| - | separated from his charge, who was received in the palace | + | |

| - | of Doih Pedro de Leon, the duke of Medina-Sidonia, | + | |

| - | where a reciprocal attachment arose between her and | + | |

| - | Ponce de Leon, son of that nobleman, and she soon after | + | |

| - | won the affections of the marquis of Montemayor, heir of | + | |

| - | the duke d'Infantada, having in the meanwhile embraced | + | |

| - | Christianity. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | At length the parents of Almahide, learning that she | + | |

| - | was in the palace of Medina Sidonia, sent to reclaim her, | + | |

| - | and she was accordingly delivered up to them. Ponce de | + | |

| - | Leon followed her to G-ranada, in the garb of a slave : in | + | |

| - | that disguise he got himself sold to Morayzel, the father | + | |

| - | of Almahide, who presented him to that lady. A similar | + | |

| - | stratagem was adopted by her other Spanish lover, who | + | |

| - | allowed himself to be taken prisoner in a skirmish with | + | |

| - | the Moors, commanded by Morayzel, who ordered him to | + | |

| - | be conducted to Granada, and presented likewise as an | + | |

| - | attendant to his daughter. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | The dissensions which arose between the two lovers | + | |

| - | thus placed around the person of their mistress, are re- | + | |

| - | strained by the prudence and temper of Almahide, but | + | |

| - | each watehes in secret an opportunity of supplanting his | + | |

| - | rival. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Meanwhile Boaudilin, king of Granada, beheld his em- | + | |

| - | pire a prey to the factions of the Zegris and Abenoerrages. | + | |

| - | As the monarch was of the former tribe, it was judged | + | |

| - | advisable, in order to heal the dissensions, that he should | + | |

| - | chuse a queen from among the latter. Unfortunately he | + | |

| - | was so deeply enamoured of Miriam, a woman of low | + | |

| - | birth, whom it would have been unsuitable to have raised | + | |

| - | to the regal dignity, that he refused to offend her by | + | |

| - | espousing another. In these circumstances, Almahide | + | |

| - | was requested to impose on the public, by performing for | + | |

| - | a season the exterior offices of queen. She readily con- | + | |

| - | sented to execute a part in this plan ; but she had scarcely | + | |

| - | entered on the public performance of royalty, when the | + | |

| - | king fell in love with her pseudo majestv, and unex- | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 442 HISTORY OF FICTION. [CH. XU. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | pectedlj proposed that she should not confine herself to | + | |

| - | the discharge of the ostensible duties of her situation. | + | |

| - | This important change in the original stipulation was re- | + | |

| - | sisted by Almahide, on the ground that her heart was | + | |

| - | already engaged to another, and the romance breaks off | + | |

| - | with an account of some ineffectual stratagems, on the | + | |

| - | part of the king, to discover for whose sake Almahide | + | |

| - | rejected a more ample participation in the cares of | + | |

| - | royalty. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | It will be perceived that the romance is left incomplete, | + | |

| - | and the part of which an abstract has been given, though | + | |

| - | published in eight volumes 8vo., can only be regarded as | + | |

| - | a sort of introductory chapter to the adventures that were | + | |

| - | intended to follow. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Mathilde d'Aguilab,* | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | the last romance of Mdlle. Scud^ry, is also a Spanish story, | + | |

| - | and is partly founded on the contests between the Chris- | + | |

| - | tians and Moors. The work consists of a sort of prologue | + | |

| - | or first part, *les Jeux servant de Preface k Mathilde | + | |

| - | (omitted in the edition of 1736) and the narrative proper | + | |

| - | of the fortunes of the heroine. The prelude or prologue, | + | |

| - | is an imitation of the framework in which the Italian | + | |

| - | novels were so often set, and the tale itself iUustrates iu | + | |

| - | different ways the influence of the Italian writers upon the | + | |

| - | authoress. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Of the analogies that subsist between all the depart- | + | |

| - | ments of Belles Lettres, none are more close than ^ose | + | |

| of romance and the drama. Accordingly, as the Italian | of romance and the drama. Accordingly, as the Italian | ||

| tales supplied the materials of our earliest tragedies and | tales supplied the materials of our earliest tragedies and | ||

| Line 729: | Line 143: | ||

| were substituted for those grotesque characters and multi- | were substituted for those grotesque characters and multi- | ||

| farious passions, which had formerly held possession of the | farious passions, which had formerly held possession of the | ||

| - | stage. From the French romances were derived the in- | + | stage. From the French romances were derived the |

| - | ^ Paris, 1667, 1 vol. ; other editions, Villefmnche, 1704 ; the Hague, | + | ^ Paris, 1667, 1 vol. ; other editions, Villefmnche, 1704 ; the Hague, 1736. Analysed in Koerting, pp. 453-457. |

| - | 1736. Analysed in Koerting, pp. 453-457. | + | |

| - | + | incidents that constitute the plots of those tragedies which | |

| - | + | appeared in the days of Charles II. and William, and to | |

| - | CH. XII.] MADEMOISELLE D£ 8CUDEBT. 443 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | cidents that constitute the plots of those tragedies which | + | |

| - | appeared in the days of Charles 11. and WilUam, and to | + | |

| them may be attributed the prevalence of that false taste, | them may be attributed the prevalence of that false taste, | ||

| that pomp and unnatural elevation, which characterize the | that pomp and unnatural elevation, which characterize the | ||

| dramatic productions of Dryden and Lee. | dramatic productions of Dryden and Lee. | ||

| - | It appears very unaccountable that such romances as | + | It appears very unaccountable that such romances as those of [[Calprenede]] and Scudery, should in foreign countries |

| - | those of Calpr^nede and Scud^ry, should in foreign countries | + | |

| have been the object of any species of literary imitation; | have been the object of any species of literary imitation; | ||

| but in their native soil the popularity of heroic romances, | but in their native soil the popularity of heroic romances, | ||

| Line 754: | Line 162: | ||

| real or imaginary resemblance. The court ladies were | real or imaginary resemblance. The court ladies were | ||

| delighted to behold flattering portraits of their beauty in | delighted to behold flattering portraits of their beauty in | ||

| - | IbnJiim or Olelia, and perhaps fondly hoped that tibeir | + | Ibrahim or Clelia, and perhaps fondly hoped that their |

| charms were consecrated to posterity. Hence the fame of | charms were consecrated to posterity. Hence the fame of | ||

| the romance was transitory as the beauty, or, at least, as | the romance was transitory as the beauty, or, at least, as | ||

| Line 775: | Line 183: | ||

| of his mistress : | of his mistress : | ||

| - | Pour meriter son ccenr pour plaire a ses beaux veux, | + | :Pour meriter son coeur pour plaire a ses beaux yeux, |

| - | J'ai fait guerre a mon roi, Je Paurois fait aux Dieux.^ | + | :J'ai fait guerre a mon roi, Je l'aurois fait aux Dieux. |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ The lines are Dn R\-er'8. La Rochefoucault wrote them beneath the | + | |

| - | portrait of Madame de Long^ueville. See (Euvres de la Comtease de La | + | |

| - | rajette, etc. Paris, 1804, vol. i., p. vii. — Lisb. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | 444 HI8T0BY OF FICTION. [CH. Xn. | + | |

| Besides, the size and prolixity of these compositions had | Besides, the size and prolixity of these compositions had | ||

| Line 790: | Line 190: | ||

| works began to abound of a shorter and more lively | works began to abound of a shorter and more lively | ||

| nature, and when the ladies had no longer leisure to | nature, and when the ladies had no longer leisure to | ||

| - | devote the attention of a year and a half to the histoiy of | + | devote the attention of a year and a half to the history of |

| - | a fair Ethiopian/ | + | a fair Ethiopian. |

| - | + | ||

| - | ^ Mdlle. Scud^rj was also the author of a couple of stories — C^linte, | + | |

| - | Paris, 1661, pp. 390; and C^lanire, Paris, 1669, 1671, and 1698, pp. | + | |

| - | 415. The novels of Scud^ry (remarks Koerting, p. 405) like those of | + | |

| - | Camus, Gromberville, and La Calpren^e, manifest no literary progress | + | |

| - | or development in their authors, and this phenomenon is a significant | + | |

| - | characteristic of the whole idealistic school, and an indication that it | + | |

| - | lacked in general the sprines of fresh pulsating life ; that its writers | + | |

| - | composed without drawing from the fund of their own intimate expe- | + | |

| - | riences, feelings, and observation — without projecting into their work | + | |

| - | their own individuality. Their romances are for the most part like the | + | |

| - | Greek tales, artificial products of the intellect, elaborated with wonderful | + | |

| - | niceties of style and composition rather than the genial production of | + | |

| - | imaginative conception. The first of Scud^ry's books is at least as good | + | |

| - | aesthetically as any of her later works. This stagnation is in noteworthy | + | |

| - | contrast to the evolution of the modem English novel by Richardson | + | |

| - | and Fielding, for instance Clarissa Harlowe could no more have been | + | |

| - | written before Pamela, than Joseph Andrews before Turn Jones. — | + | |

| - | EoERTiva, p. 405. | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Among the numerous minor authors of the school of idealistic romance | + | |

| - | are several who may be briefly commemorated before we quit the sub- | + | |

| - | ject. Fran9ois Sieur de Moliere et d'Essartines (bom about 1600, killed | + | |

| - | 1623) published in 1620 a collection of stories under the title of ** La | + | |

| - | Semaine Amoureuse," and subsequently one volume (books i. — iv.) of | + | |

| - | the half* past oral, half-heroic romance La Polix^ne, or Les Advantures | + | |

| - | de Polixine (Paris, 1623), dedicated to the Princess Conti. The book | + | |

| - | was very popular, and a continuation was published in 1632, and | + | |

| - | another, Vraye Suite des Aduantures de la Polixene . . . suivie et con- | + | |

| - | clue sur ses Memoires, in 1634. Sorel, who criticizes the work very un- | + | |

| - | favourably in his Berger Extravagant (I. xiii.), describes it as nothing | + | |

| - | more or less than an expansion of the Daphnis episode given at the | + | |

| - | beginning of vol. iii. of the Astrte. Sorel, however, believed he would | + | |

| - | have achieved better things if he had not, like Audiguier, prematurely | + | |

| - | met his death at the hand of one he believed his friend. This Audiguier | + | |

| - | was the author of Lisandre and Caliste, dramatized by Du Ryer in 1632. | + | |

| - | and Les Amours d'Aristandre et de Cl^onioe, noticed in Sorel's ** Be- | + | |

| - | marques," p. 495, etc. (See Koerting, pp. 381-384.) | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | Fran9ois du S^ucy, Sieur de Gerzan (born towards end of sixteenth | + | |

| - | century )first and most important romance, Histoire Afriquoine de Cl^ | + | |

| - | mede et de Sophonisbe (Paris, pt. L, 1627, pts. II., III., 162$). De Gernn | + | |

| - | purposed to write romances, the scenes of which were to be the other three | + | |

| - | continents ; the heroes he deals with are none other than Scipio, Alex- | + | |

| - | ander, Charles V., Henry IV., and Louis XIII. , and his narrative is not | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | + | ||

| - | CH. XII.] HEBOIG BOHANOE. 445 | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | In addition to all this, the heroic romance, when verging | + | |

| - | to its decline, was attacked by genius almost equal to that | + | |

| - | by which the tales of chivalry had formerly been laughed | + | |

| - | out of countenance. Molifere's " Pr^cieuses Bidicules " | + | |

| - | appeared in 1659, when the heroic romance was too much | + | |

| - | in vogue to be easily brought into discredit ; but the satire | + | |

| - | of Boileau, entitled Les Heros de Boman, Dialogue, though | + | |

| - | written about the same period, was not published till after | + | |

| - | the death of Mdlle. Scudery, in 1701, by which time the | + | |

| - | reputation of her romances was on the wane, and was | + | |

| - | probably still farther shaken by the ridicule of Boileau. | + | |

| - | That poet informs us, that in his youth, when these works | + | |

| - | were in fashion, he had perused them with much admira- | + | |

| - | tion, and regarded them as the master-pieces of the lan- | + | |

| - | guage. As his taste, however, improved, he became alive | + | |

| - | to their absurdities, and composed the dialogue above- | + | |

| - | mentioned, which he declares to be "Le moins frivole | + | |

| - | ouvrage qui soit encore sorti de ma plume." In this work | + | |

| - | the scene is laid in the dominions of Pluto, who complains | + | |

| - | to Minos, that the shades which descend from earth no | + | |

| - | longer possess common sense, that they all talk galanterie, | + | |

| - | + | ||

| - | to ofiend *' a chaste and honorable ear." The chief materials of the | + | |

| - | romance are drawn firom the Amadis and from the Greek erotic romances. | + | |

| - | The beginning is imitated from Heliodorns, and other features are | + | |

| - | borrowed from lamblichus and Xenophon, diluted with a liberal amount | + | |

| - | of alchymical trash, vital elixirs, potable gold, concoctions for making | + | |

| - | the fair sex fair for ever, etc., much ridiculed by Sorel in his Polyandre, | + | |

| - | and by Cyrano in Voyage a la Lane. A German translation of the | + | |

| - | work by *< der Fiirtige,^ t>., Philipp Zesen (1689)— Die Afrikanische | + | |

| - | Sophonisbe, Frankfurt, sold by Johann David Zunnern, 1674 — was dedi- | + | |

| - | cated to Queen Christina of Sweden. An analysis of this version is given | + | |

| - | by Cholevius, p. 29. (See supra, vol. i., p. 20.) | + | |

| - | + | ||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| - | *''[[Mademoiselle Scuderi]]'' | + | *''[[Mademoiselle Scuderi]]'' by Hoffmann |

| - | === Articles connexes === | + | |

| * [[Les femmes et les salons littéraires]] | * [[Les femmes et les salons littéraires]] | ||

| * [[Salon littéraire]] | * [[Salon littéraire]] | ||

| Line 884: | Line 199: | ||

| * [[Carte du Tendre|Carte de Tendre]] | * [[Carte du Tendre|Carte de Tendre]] | ||

| * [[Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus]] | * [[Artamène ou le Grand Cyrus]] | ||

| + | *''[[The Women of the French Salons]]'' (New York, 1891) by Amelia Gere Mason | ||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

"Chapelain and Pelisson were her friends, as were also the Abbé Godeau better known as "le Nain de Julie," and Madame de Scudery, ugly, courtly, and clever, the Richardson of romance - at least in length."--The Gentleman's Magazine "Her and her brother's heroes never enter an apartment until all the furniture has been inventoried."--"Les héros de roman" by Boileau "The most voluminous writer of heroic romance is Mmle de Scudery, whose numerous productions amount to near fifty volumes."--History of Fiction (1814) by John Colin Dunlop "The whole romance is loaded with tedious descriptions of the interior of Turkish and Italian palaces, which has given rise to the remark of Boileau, that when one of Mad. Scudery's characters enters a house, she will not permit him to leave it till she has given an inventory of the furniture."--History of Fiction (1814) by John Colin Dunlop "She expresses so delicately the most difficult feelings to express and she knows so well how to painting the anatomy of the loving heart … She knows how to describe all the jealousies, all the anxieties, all the impatiences, all the joys, all the disgusts, all the murmurs, all the despairs, all the hopes, all the revolts and all those tumultuous feelings that are never well known except to those who feel them or have felt them."--Madeleine de Scudéry describing herself in vol. 10 of Artamène, using the pseudonym Sapho, tr. JWG A lover who is afraid of thieves --Mademoiselle de Scudéri (1819) is a novella by E. T. A. Hoffmann "But what has chiefly excited ridicule in this romance, is the Carte du pays de Tendre prefixed in the map of this imaginary land, there is laid down the river D'Inclination, on the right bank of which are situated the villages of Jolis vers, and Epitres Galantes; and on the left those of Complaisance, Petits soins and Assiduites. Farther in the country are the cottages of Légereté and Oubli, with the lake Indifference. By one route we are led to the district of Desertion and Perfidie, but by sailing down the stream, we arrive at the towns Tendre sur Estime, Tendre sur Inclination, etc."--History of Fiction (1814) by Dunlop |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Madeleine de Scudéry (1607 – 1701) was a French writer best known for the novel sequence Clélie (1654-1660).

Contents |

Overview

In 1637, following the death of her uncle, Scudéry established herself in Paris with her brother. Georges de Scudéry became a playwright.

Madeleine often used her older brother's name, George, to publish her works. She was at once admitted to the Hôtel de Rambouillet coterie of préciosité, and afterwards established a salon of her own under the title of the Société du samedi (Saturday Society).

For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of Sapho or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first bluestocking of France and of the world.

She formed a close romantic relationship with Paul Pellisson which was only ended by his death in 1693. She never married.

Her works demonstrate such comprehensive knowledge of ancient history that it is presumed she had received instruction in Greek and Latin.

Influence

The romances of Madeleine de Scudéry gained great influence with plots situated in the ancient world and content taken from life. The famous author told stories of her friends in the literary circles of Paris and developed their fates from volume to volume of her serialised production. Readers of taste bought her books, as they offered the finest observation of human motives, characters taken from life, excellent morals regarding how one should and should not behave if one wanted to succeed in public life and in the intimate circles she portrayed.

Criticism by Sainte-Beuve

In Portraits Of The Seventeenth Century Historic And Literary (1909)[1] Sainte-Beuve said that her books are unreadable:

- It is true that her books are unreadable now and exasperating to literary taste; but we should remember that she made part of a great pioneer work, in which all the actors laid stepping-stones by which social life, literature, manners, refinement, the status of women, were to rise, and rise rapidly to higher things. With this before our minds we can overlook the Carte du Tendre (Map of the Country of Tenderness) which, by the way, was only a bit of private nonsense which her friends unwisely persuaded her to put into Clelie and turn to her solid advice to women, given in her Grand Cyrus:

But Saint-Beuve also commends her for encouraging women to learn how to read:

- I leave you to judge whether I am wrong in wishing that women should know how to read, and read with application. There are some women of great natural parts who never read anything; and what seems to me the strangest thing of all is that those intelligent women prefer to be horribly bored when alone, rather than accustom themselves to read, and so gather company in their minds by choosing such books, either grave or gay, as suit their inclinations. It is certain that reading enlightens the mind so clearly and forms the judgment so well that without it conversation can never be as apt or as thorough as it might be. ... I want women to be neither learned nor ignorant, but to employ a little better the advantages that nature has given them, I want them to adorn their minds as well as their persons. This is not incompatible with their lives; there are many agreeable forms of knowledge which women may acquire thoroughly without departing from the modesty of their sex, provided they make good use of them. And I therefore wish with all my heart that women's minds were less idle than they are, and that I myself might profit by the advice I give to others."

- (tr. Katherine Prescott Wormeley)

Works

Her lengthy novels, such as Artamène, ou le Grand Cyrus (10 vols., 1648-53), Clélie (10 vols., 1654-61), Ibrahim, ou l'illustre Bassa (4 vols., 1641), Almahide, ou l'esclave reine (8 vols., 1661-3) were the delight of Europe, commended by other literary figures such as Madame de Sévigné. Artamène, which contains about 2.1 million words, ranks as one of the longest novels ever written. These stories derive their length from endless conversations and, as far as incidents go, successive abductions of the heroines, conceived and told decorously.

Scudéry's novels are usually set in the classical world or the Orient, but their language and action reflect fashionable ideas of the 17th century, and the characters can be identified with Mademoiselle de Scudéry's contemporaries. In Clélie, Herminius represents Paul Pellisson; Scaurus and Lyriane were Paul Scarron and his wife (who became Mme de Maintenon); and in the description of Sapho in vol. 10 of Le Grand Cyrus the author paints herself.

In Clélie, Scudéry invented the famous Carte du Tendre, a map of an Arcadia where the geography is all based around the theme of love: the river of Inclination flows past the villages of "Billet Doux" (Love Letter), "Petits Soins" (Little Trinkets) and so forth. Scudéry was a skilled conversationalist; several volumes purporting to report her conversations upon various topics were published during her lifetime. She had a distinct vocation as a pedagogue. She could moralize—a favourite employment of the time—with sense and propriety.

Controversial in her own era, Mlle de Scudéry was satirized by Molière in his plays Les Précieuses ridicules (1659) and Les Femmes savantes (1672) and by Antoine Furetière in his Roman Bourgeois (1666).

The 19th century German short-story writer E.T.A. Hoffmann wrote what is usually referred to as the first German-language detective story, featuring Scudéry as the central figure. "Das Fräulein von Scuderi" (Mademoiselle de Scudery) is still widely read today, and is the origin of the "Cardillac syndrome" in psychology.

Biography

Born at Le Havre, Normandy, in northern France, she is said to have been very plain as well as without fortune, but she was very well educated. Establishing herself at Paris with her brother, she was at once admitted to the Hôtel de Rambouillet coterie, and afterwards established a salon of her own under the title of the Société du samedi (Saturday Society). For the last half of the 17th century, under the pseudonym of Sapho or her own name, she was acknowledged as the first bluestocking of France and of the world. She formed a close friendship with Paul Pellisson which was only ended by his death in 1693.

Later years

Madeleine survived her brother by more than thirty years, and in her later days published numerous volumes of conversations, to a great extent extracted from her novels, thus forming a kind of anthology of her work. She outlived her vogue to some extent, but retained a circle of friends to whom she was always the "incomparable Sapho."

Her Life and Correspondence was published at Paris by MM. Rathery and Boutron in 1873.