Nietzsche's collapse and mental breakdown

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

"In Turin on 3rd January, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six, Via Carlo Alberto. Not far from him, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and puts an end to the brutal scene, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words, 'Mutter, ich bin dumm!' ['Mother, I am stupid!' in German] and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, cared for by his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse." --Béla Tarr’s introductory words to The Turin Horse |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

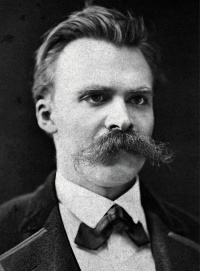

On 3 January 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche suffered a mental breakdown. Two policemen approached him after he caused a public disturbance in the streets of Turin. What happened remains unknown, but an often-repeated tale from shortly after his death states that Nietzsche witnessed the flogging of a horse at the other end of the Piazza Carlo Alberto, ran to the horse, threw his arms up around its neck to protect it, and then collapsed to the ground.

In the following few days, Nietzsche sent short writings—known as the Wahnbriefe ("Madness Letters")—to a number of friends including Cosima Wagner and Jacob Burckhardt. Most of them were signed "Dionysos". To his former colleague Burckhardt, Nietzsche wrote: "I have had Caiaphas put in fetters. Also, last year I was crucified by the German doctors in a very drawn-out manner. Wilhelm, Bismarck, and all anti-Semites abolished." Additionally, he commanded the German emperor to go to Rome to be shot and summoned the European powers to take military action against Germany.

On 6 January 1889, Burckhardt showed the letter he had received from Nietzsche to Franz Overbeck. The following day Overbeck received a similar letter and decided that Nietzsche's friends had to bring him back to Basel. Overbeck travelled to Turin and brought Nietzsche to a psychiatric clinic in Basel. By that time Nietzsche appeared fully in the grip of a serious mental illness, and his mother Franziska decided to transfer him to a clinic in Jena under the direction of Otto Binswanger. From November 1889 to February 1890, the art historian Julius Langbehn attempted to cure Nietzsche, claiming that the methods of the medical doctors were ineffective in treating Nietzsche's condition. Langbehn assumed progressively greater control of Nietzsche until his secretiveness discredited him. In March 1890, Franziska removed Nietzsche from the clinic and, in May 1890, brought him to her home in Naumburg. During this process Overbeck and Gast contemplated what to do with Nietzsche's unpublished works. In January 1889 (date seems out of order), they proceeded with the planned release of Twilight of the Idols, by that time already printed and bound. In February, they ordered a fifty-copy private edition of Nietzsche Contra Wagner, but the publisher C. G. Naumann secretly printed one hundred. Overbeck and Gast decided to withhold publishing The Antichrist and Ecce Homo because of their more radical content. Nietzsche's reception and recognition enjoyed their first surge.

In 1893, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth returned from Nueva Germania in Paraguay following the suicide of her husband. She read and studied Nietzsche's works and, piece by piece, took control of them and their publication. Overbeck eventually suffered dismissal and Gast finally co-operated. After the death of Franziska in 1897, Nietzsche lived in Weimar, where Elisabeth cared for him and allowed visitors, including Rudolf Steiner (who in 1895 had written one of the first books praising Nietzsche), to meet her uncommunicative brother. Elisabeth at one point went so far as to employ Steiner as a tutor to help her to understand her brother's philosophy. Steiner abandoned the attempt after only a few months, declaring that it was impossible to teach her anything about philosophy.

Nietzsche's mental illness was originally diagnosed as tertiary syphilis, in accordance with a prevailing medical paradigm of the time. Although most commentators regard his breakdown as unrelated to his philosophy, Georges Bataille dropped dark hints ("Man incarnate' must also go mad") and René Girard's postmortem psychoanalysis posits a worshipful rivalry with Richard Wagner. Nietzsche had previously written, "all superior men who were irresistibly drawn to throw off the yoke of any kind of morality and to frame new laws had, if they were not actually mad, no alternative but to make themselves or pretend to be mad" (Daybreak,14). The diagnosis of syphilis has since been challenged and a diagnosis of "manic-depressive illness with periodic psychosis followed by vascular dementia" was put forward by Cybulska prior to Schain's study. Orth and Trimble postulated frontotemporal dementia while other researchers have proposed a syndrome called CADASIL.

In 1898 and 1899 Nietzsche suffered at least two strokes which partially paralyzed him, leaving him unable to speak or walk. He likely suffered from clinical hemiparesis/hemiplegia on the left side of his body by 1899. After contracting pneumonia in mid-August 1900, he had another stroke during the night of 24–25 August and died at about noon on 25 August. Elisabeth had him buried beside his father at the church in Röcken bei Lützen. His friend and secretary Gast gave his funeral oration, proclaiming: "Holy be your name to all future generations!" Nietzsche had written in Ecce Homo (at that point still unpublished) of his fear that one day his name would be regarded as "holy".

Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche compiled The Will to Power from Nietzsche's unpublished notebooks and published it posthumously. Because his sister arranged the book based on her own conflation of several of Nietzsche's early outlines and took great liberties with the material, the scholarly consensus has been that it does not reflect Nietzsche's intent. (For example, Elisabeth removed aphorism 35 of The Antichrist, where Nietzsche rewrote a passage of the Bible.) Indeed, Mazzino Montinari, the editor of Nietzsche's Nachlass, called it a forgery.

See also