Thérèse the Philosopher

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 22:57, 16 April 2010 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 21:37, 30 December 2010 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) Next diff → |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| ==Philosophical and social concepts== | ==Philosophical and social concepts== | ||

| - | For all of its printed [[debauchery]], the work has philosophical [[merit]] in its underlying [[enlightenment ideals]]. Between the more [[pornographic|graphically adult]] sections of the novel, philosophical issues would be discussed amongst the characters. | + | For all of its printed [[debauchery]], the work has philosophical [[merit]] in its underlying [[enlightenment ideals]]. Between the more [[pornographic|graphically adult]] sections of the novel, philosophical issues would be discussed amongst the characters, including [[materialism]], [[hedonism]] and [[atheism]]. All phenomena are matter in motion, and religion is a fraud, though useful for keeping the working classes in line.. |

| The book not only draws attention to the [[sexual repression]] of women at the time of the enlightenment, but also to the exploitation of religious authority through [[salacious]] acts. | The book not only draws attention to the [[sexual repression]] of women at the time of the enlightenment, but also to the exploitation of religious authority through [[salacious]] acts. | ||

Revision as of 21:37, 30 December 2010

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

- Venus in France, French materialism

- See full text here

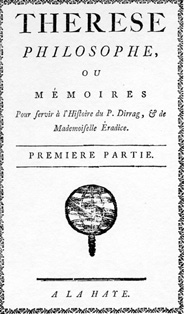

Thérèse Philosophe is a 1748 anonymously published French novel variously ascribed to Jean-Baptiste de Boyer, Marquis d'Argens, Denis Diderot, Xavier d'Arles de Montigny and Théodore-Henri de Tschudi.

Thérèse philosophe was devoted to recounting the relationship between the jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste Girard and his student Cathérine Cadière. "Father Dirrag" and "Mlle. Eradice" are named after anagrams of Catherine Cadière and Jean-Baptiste Girard. Their illicit relationship ended in a highly-publicized trial in 1730.

This novel was written and published in France, during the Age of Enlightenment. It has been chiefly regarded as a pornographic novel, which accounts for its massive sales in 18th-century France (as pornographic works were the most popular bestsellers of the time, see Darnton). Aside from that however, this novel represents a public conveyance (and arguably perversion) for some ideas of the Philosophes.

The characters borrowed from real life are thinly disguised by the anagrammatic names, and a such, consitutes a roman à clef.

Contents |

Philosophical and social concepts

For all of its printed debauchery, the work has philosophical merit in its underlying enlightenment ideals. Between the more graphically adult sections of the novel, philosophical issues would be discussed amongst the characters, including materialism, hedonism and atheism. All phenomena are matter in motion, and religion is a fraud, though useful for keeping the working classes in line..

The book not only draws attention to the sexual repression of women at the time of the enlightenment, but also to the exploitation of religious authority through salacious acts.

- "C’est l’amour-propre, me disiez-vous un jour, qui décide de toutes les actions de notre vie. J’entends par amour-propre cette satisfaction intérieure que nous sentons à faire telle ou telle chose. Je vous aime, par exemple, parce que j’ai du plaisir à vous aimer. Ce que j’ai fait pour vous peut vous convenir, vous être utile, mais ne m’en ayez aucune obligation : c’est l’amour-propre qui m’y a déterminé, c’est parce que j’ai fixé mon bonheur à contribuer au vôtre, et c’est par ce même motif que vous ne me rendrez parfaitement heureux que lorsque votre amour-propre y trouvera sa satisfaction particulière."

The medical materialism of Holbach

- "nous ne sommes pas plus maîtres de penser de telle et de telle manière, d’avoir telle ou telle volonté, que nous ne sommes les maîtres d’avoir ou de ne pas avoir la fièvre. En effet, ajoutiez-vous, nous voyons, par des observations claires et simples, que l’âme n’est maîtresse de rien, qu’elle n’agit qu’en conséquence des sensations et des facultés du corps, que les causes qui peuvent produire du dérangement dans les organes troublent l’âme, altèrent l’esprit, qu’un vaisseau, une fibre, dérangés dans le cerveau peuvent rendre imbécile l’homme du monde qui a le plus d’intelligence. Nous savons que la nature n’agit que par les voies les plus simples, que par un principe uniforme. Or, puisqu’il est évident que nous ne sommes pas libres dans de certaines actions, nous ne le sommes dans aucune."

Thérèse concludes:

- "Je vous le répète donc, censeurs atrabilaires, nous ne pensons pas comme nous voulons. L’âme n’a de volonté, n’est déterminée que par les sensations, que par la matière, La raison nous éclaire, mais elle ne nous détermine point. L’amour-propre (le plaisir à espérer ou le déplaisir à éviter) sont le mobile de toutes nos déterminations."

Summary

The narrative starts with Therese, from solid bourgeois stock, becoming a student of Father Dirrag, a Jesuit who secretly teaches materialism. Therese spies on Dirrag counseling her fellow student, Mlle. Eradice, and preying on her spiritual ambition to seduce her. Through flagellation and penetration, he gives her what she thinks is spiritual ecstasy but is actually sexual.

After a flagellation scene, Father Dirrag, gives Eradice his "holy relic".

- 'Oh, venerable Father,' exclaimed Eradice, 'I cannot describe the delights that are flowing through me! Oh, yes, yes, I experience Heavenly bliss. I can feel how my spirit is being liberated from all earthly desires. Please, please, dearest Father, exorcise every last impurity remaining upon my tainted soul. I can see . . .the angels of God . . . push stronger . . . ooh . . . shove the holy relic deeper . . .deeper. Please, dearest Father, shove it as hard as you can . . . Ooooh! . . . oooh!!! Dearest holy Saint Francis . . . Ooh, good saint . . . please, don't leave me in the hour of my greatest need . . . I feel your relic . . . it is so good . . . your . . . holy . . . relic . . . I can't hold it any longer . . . I am . . . dying!'

The relic is the Cord of Saint Francis, but in reality no less than the penis of the monk taking the innocent girl.

Therese is placed in a convent, where she becomes sick because her pleasure principle is not allowed to express itself, putting her body into disorder. She is rescued by Mme. C and Abbe T. and she spies on them discussed libertine political and religious philosophy in between sexual encounters.

Therese's sexual education continues with her relationship with Mme. Bois-Laurier, an experienced prostitute. This is a variation on the whore dialogues common in early pornographic novels.

Finally, Therese meets the unnamed Count who wants her for his mistress. She refuses him intercourse, out of her fear of death in childbirth (not unreasonable at the time.) He makes a bet with her. If she can last two weeks in a room full of erotic books and paintings without masturbating, he will not demand intercourse with her.

- "Tout fut porté par vos ordres dans ma chambre. Je dévorai des yeux ou, pour mieux dire, je parcourus tour à tour pendant les quatre premiers jours l'histoire du Portier des Chartreux, celle de La Tourière des Carmélites, L'Académie des Dames, Les Lauriers ecclésiastiques, Thémidore, Frétillon, etc., et nombre d’autres de cette espèce, que je ne quittai que pour examiner avec avidité des tableaux où les postures les plus lascives étaient rendues avec un coloris et une expression qui portaient un feu brûlant dans mes veines."

Therese loses and becomes the Count's permament mistress.

English translations

The first translation of this work was as The Philosophical Theresa was published by George Cannon or J. B. Brookes, [c.1830]. It was later published by William Dugdale as Society of Vice (c.1860) in 2 volumes with 16 lithographs and again by Charles Carrington in 1900.

Trivia

Thérèse Philosophe was mentioned in Dostoevsky's The Gambler.

See also