Transgressive fiction

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

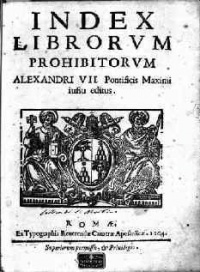

Illustration: Index Librorum Prohibitorum ("List of Prohibited Books") of the Catholic Church.

|

"I am a sick man. ... I am a spiteful man." --incipit to Notes from Underground (1864) by Fyodor Dostoevsky "It takes at least three months’ shooting twice a day to get any habit at all. And you don’t really know what junk sickness is until you have had several habits. It took me almost six months to get my first habit, and then the withdrawal symptoms were mild. I think it no exaggeration to say it takes about a year and several hundred injections to make an addict." --preface to Junkie, William S. Burroughs "Did it date from so far back, from the harm women had done to his race, from the rancour laid up from male to male since the first deceptions at the bottom of the caverns?"--Jacques Lantier, protagonist of La Bête humaine (1890), wondering why he desires to kill women he does not even know "I am filthy. I am riddled with lice. Hogs, when they look at me, vomit. --Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) by Comte de Lautréamont [...] "One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin. He lay on his armour-like back, and if he lifted his head a little he could see his brown belly, slightly domed and divided by arches into stiff sections. The bedding was hardly able to cover it and seemed ready to slide off any moment. His many legs, pitifully thin compared with the size of the rest of him, waved about helplessly as he looked."--The Metamorphosis (1915) by Franz Kafka "Oh, Juliette! forget it, scorn it, the concept of this vain and ludicrous God. His existence is a shadow instantly to be dissipated by the least mental effort, and you shall never know any peace so long as this odious chimera preserves any of its prize upon your soul which error would give to it in bondage. Refer yourself again and again to the great theses of Spinoza, of Vanini, of the author of Le Systeme de la Nature."--Juliette (1797–1801) by Marquis de Sade, tr. Austryn Wainhouse |

Illustration: Portrait fantaisiste du marquis de Sade (1866) by H. Biberstein

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Transgressional fiction or transgressive fiction is a genre of literature that focuses on characters who feel confined by the norms and expectations of society and who use unusual and/or illicit ways to break free of those confines. Because they are rebelling against the basic norms of society, protagonists of transgressional fiction may seem mentally ill, anti-social and/or nihilistic. The genre deals extensively with abnormal psychology and taboo subject matters such as drugs, sex, violence, incest, pedophilia, and crime.

Contents |

Literary context

Michel Foucault's essay "A Preface to Transgression" (1963) provides an important methodological origin for the concept of transgression in literature. The essay uses Story of the Eye by Georges Bataille as an example of transgressive fiction.

Rene Chun, a journalist for The New York Times, described transgressive fiction:

- "A literary genre that graphically explores such topics as incest and other aberrant sexual practices, mutilation, the sprouting of sexual organs in various places on the human body, urban violence and violence against women, drug use, and highly dysfunctional family relationships, and that is based on the premise that knowledge is to be found at the edge of experience and that the body is the site for gaining knowledge."

The genre has been the subject of controversy, and many forerunners of transgressive fiction, including William S. Burroughs and Hubert Selby Jr., have been the subjects of obscenity trials.

Transgressive fiction shares similarities with splatterpunk, noir, and erotic fiction in its willingness to portray forbidden behaviors and shock readers. But it differs in that protagonists often pursue means to better themselves and their surroundings—albeit unusual and extreme ones. Much transgressive fiction deals with searches for self-identity, inner peace, or personal freedom. Unbound by usual restrictions of taste and literary convention, its proponents claim that transgressive fiction is capable of incisive social commentary.

The genre overlaps somewhat with literary minimalism, in that many transgressive writers use short sentences and simplistic style.

History

The basic ideas of transgressive fiction are by no means new. Many works that are now considered classics dealt with controversial themes and harshly criticized societal norms. Early examples include the scandalous writing of the Marquis de Sade and the Comte de Lautreamont's Les Chants de Maldoror (1869). French author Émile Zola's works about social conditions and “bad behavior” are examples, as are Russian Fyodor Dostoyevsky's existentialist novels Crime and Punishment (1866) and Notes from Underground (1864) and Norwegian Knut Hamsun's psychologically-driven Hunger (1890). Sexual extravangance can be seen in two of the earliest European novels, the Satyricon and The Golden Ass, and also (with disclaimers) Moll Flanders, and some of the excesses of early Gothic fiction.

Early twentieth-century writers such as Octave Mirbeau, Georges Bataille and Arthur Schnitzler, who pungently explored psychosexual development, are also important forebears.

On 6 December 1933, Judge John M. Woolsey overturned the federal ban on James Joyce's Ulysses. The book was banned in the U.S. due to what the government claimed was obscenity, specifically the (approximately) 90-page sex scene, depending on the version. Random House Inc. came to the United States District Court to battle the claim of obscenity and be granted permission to print the book in the United States. Judge Woolsey is often quoted explaining his removal of the ban by saying "It is only with the normal person that the law is concerned."

In the late 1950s, American publisher Grove Press, under publisher Barney Rosset, began releasing decades-old novels that had been unpublished in most of the English-speaking world for many years due to controversial subject matter. Two of these works, Lady Chatterley's Lover, D. H. Lawrence’s tale of an upper class woman’s affair with a working class man and Tropic of Cancer, Henry Miller’s sexual odyssey, were the subject of landmark obscenity trials (Lady Chatterley's Lover was also tried in the UK and Austria). Both books were ruled not obscene and forced the US literary establishment to weigh the merit of literature that would have once been instantly deemed pornographic (see Miller test).

Grove also published the explicit works of Beat writers, which led to two more obscenity trials. The first concerned Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s 1955 poem which celebrated American counterculture and decried hypocrisy and emptiness in mainstream society. The second concerned William S. Burroughs’ hallucinatory, satirical novel Naked Lunch (1959). Both works contained what were considered lewd descriptions of body parts and sexual, often homosexual, acts. Grove also published Hubert Selby Jr.’s anecdotal novel Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964), known for its gritty portrayals of criminals, prostitutes and transvestites and its crude, slang-inspired prose. Last Exit to Brooklyn was tried as obscene in the UK. These trials, all of which Grove Press won, paved the way both for transgressive fiction to be published legally, as well as bringing attention to these works.

In the 1970s and 80s, an entire underground of transgressive fiction flourished. Its biggest stars included J.G. Ballard, a British writer known for his strange and frightening dystopian novels; Kathy Acker, an American known for her sexually blunt but still feminist fiction and Charles Bukowski, an American known for his tales of womanizing, drinking and gambling. The notorious 1971 film version of Anthony Burgess's A Clockwork Orange, contained scenes of rape and "ultraviolence" by a futuristic youth gang complete with its own argot, and was a major influence on popular culture; it was subsequently withdrawn in the UK, and heavily censored in the USA. Its author claimed it as a morality tale.

In the 1990s, the rise of alternative rock and its distinctly downbeat subculture opened the door for transgressive writers to become more influential and commercially successful than ever before. This is exemplified by the influence of Canadian Douglas Coupland’s 1990 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, which explored the economically bleak and apocalypse-fixated worldview of Coupland's age group. The novel popularized the term generation X to describe this age demographic. Other influential authors of this decade include Bret Easton Ellis, known for novels about depraved yuppies; Irvine Welsh known for his portrayals of Scotland’s drug-addicted working class youth and Chuck Palahniuk, known for his characters' bizarre attempts to escape bland consumer culture. Both of Elizabeth Young's volumes of literary criticism from this period deal extensively and exclusively with this range of authors and the contexts in which their works can be viewed.

In the UK, the genre owes a considerable influence to “working class literature”, which often portrays characters trying to escape poverty by inventive means while, in the US, the genre focuses more on middle class characters trying to escape the emotional and spiritual limitations of their lifestyle.

Notable works

- Junkie (1953)

- Naked Lunch (1959)

- Lolita (1955)

- Ada or Ardor (1969)

- Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964)

- Requiem for a Dream (1978)

- The Atrocity Exhibition (1970)

- Crash (1973)

- Almost Transparent Blue (1976)

- Less Than Zero (1985)

- American Psycho (1991)

- Frisk (1991)

- Trainspotting (1993)

- Filth (1998)

- Fight Club (1996)

- Invisible Monsters (1999)

- Haunted (2005)

See also