Travel literature

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 20:04, 4 March 2013 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| + | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | "The [[Alps]] […] fill the mind with an agreeable kind of [[horror]]."--''[[Remarks on Several Parts of Italy]]'' (1705) by Joseph Addison | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "It is a [[curious]] fact that of that class of literature to which [[Baron Munchausen|Munchausen]] belongs, that namely of _[[Imaginary voyage |Voyages Imaginaires]]_, the three great types should have all been created in England. ''[[Utopia (book)|Utopia]]'', ''[[Robinson Crusoe]]'', and ''[[Gulliver's Travels|Gulliver]]'', illustrating respectively the philosophical, the edifying, and the satirical type of fictitious travel, were all written in England, and at the end of the eighteenth century a fourth type, the fantastically [[mendacious]], was evolved in this country."--1895 edition of ''[[Baron Munchausen]]'' | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "A little beyond this, we got into a [[sea]], not of water, but of [[milk]]; and upon it we saw an island full of vines; this whole island was one compact well-made cheese ... The vines have grapes upon them, which yield not wine, but milk." --''[[A True Story]]'' (2nd century) by Lucian | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "You have no need to have read [[Payne Knight]], or [[Louis Viardot]], or [[John Ruskin]], to be able to understand [[Mont Blanc]]. The [[Grands Mulets]] and the [[Mer de Glace]] would interest the merest [[clodhopper]]. This is the reason why [[Switzerland]] is with [[travellers]] an universal favourite. You can’t wrangle about the conflict of styles in a [[precipice]]; the ''[[odium theologicum]]'' has nothing to lay hold of in an [[avalanche]]."--''[[Rome and Venice: With Other Wanderings in Italy, in 1866-7]]'' (1869) by George Augustus Sala | ||

| + | |} | ||

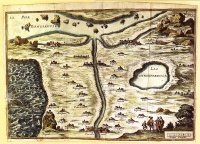

| + | [[Image:Carte du tendre.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The ''[[Map of Tendre]]'' (''Carte du Tendre'')]] | ||

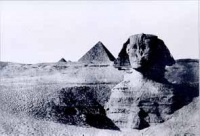

| + | [[Image:The Sphinx by Maxime Du Camp, 1849.jpg|thumb|right|200px|[[The Great Sphinx of Giza (photo by Maxime Du Camp)]]]] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| '''Travel literature''' is [[travel writing]] considered to have value as [[literature]]. Travel literature typically records the people, events, sights and feelings of an author who is [[tourism|touring]] a foreign place for the pleasure of [[travel]]. An individual work is sometimes called a '''travelogue''' or '''itinerary'''. | '''Travel literature''' is [[travel writing]] considered to have value as [[literature]]. Travel literature typically records the people, events, sights and feelings of an author who is [[tourism|touring]] a foreign place for the pleasure of [[travel]]. An individual work is sometimes called a '''travelogue''' or '''itinerary'''. | ||

| Line 4: | Line 16: | ||

| To be called literature the work must have a coherent [[narrative]], or insights and value, beyond a mere logging of dates and events, such as [[travel diary|diary]] or [[ship's log]]. Literature that recounts [[adventure]], [[exploration]] and conquest is often grouped under travel literature, but it also has its own genre [[outdoor literature]]; these genres will often overlap with no definite boundaries. This article focuses on literature that is more akin to tourism. | To be called literature the work must have a coherent [[narrative]], or insights and value, beyond a mere logging of dates and events, such as [[travel diary|diary]] or [[ship's log]]. Literature that recounts [[adventure]], [[exploration]] and conquest is often grouped under travel literature, but it also has its own genre [[outdoor literature]]; these genres will often overlap with no definite boundaries. This article focuses on literature that is more akin to tourism. | ||

| ==Fiction== | ==Fiction== | ||

| - | :''[[fictional travelogue]] | + | :''[[imaginary voyage ]] |

| [[Fiction]]al travelogues make up a large proportion of travel literature. Although it may be desirable in some contexts to distinguish [[fiction]]al from [[non-fiction]]al works, such distinctions have proved notoriously difficult to make in practice, as in the famous instance of the travel writings of [[Marco Polo]] or [[John Mandeville]]. Many "fictional" works of travel literature are based on factual journeys – [[Joseph Conrad]]'s ''[[Heart of Darkness]]'' and presumably, [[Homer]]'s ''[[Odyssey]]'' (c. 8th century BCE) – while other works, though based on imaginary and even highly fantastic journeys – [[Dante Alighieri|Dante]]'s ''[[Divine Comedy]]'', [[Jonathan Swift]]'s ''[[Gulliver's Travels]]'', [[Voltaire]]'s ''[[Candide]]'' or [[Samuel Johnson]]'s ''[[The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia]]'' – nevertheless contain factual elements. | [[Fiction]]al travelogues make up a large proportion of travel literature. Although it may be desirable in some contexts to distinguish [[fiction]]al from [[non-fiction]]al works, such distinctions have proved notoriously difficult to make in practice, as in the famous instance of the travel writings of [[Marco Polo]] or [[John Mandeville]]. Many "fictional" works of travel literature are based on factual journeys – [[Joseph Conrad]]'s ''[[Heart of Darkness]]'' and presumably, [[Homer]]'s ''[[Odyssey]]'' (c. 8th century BCE) – while other works, though based on imaginary and even highly fantastic journeys – [[Dante Alighieri|Dante]]'s ''[[Divine Comedy]]'', [[Jonathan Swift]]'s ''[[Gulliver's Travels]]'', [[Voltaire]]'s ''[[Candide]]'' or [[Samuel Johnson]]'s ''[[The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia]]'' – nevertheless contain factual elements. | ||

| [[Jack Kerouac]]'s ''[[On the Road]]'' (1957) and ''[[The Dharma Bums]]'' (1958) are fictionalized accounts of his travels across the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. | [[Jack Kerouac]]'s ''[[On the Road]]'' (1957) and ''[[The Dharma Bums]]'' (1958) are fictionalized accounts of his travels across the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==History== | ||

| + | |||

| + | Early examples of travel literature include [[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]]' ''Description of Greece'' in the 2nd century CE, [[Safarnama]] (book of Travels) of [[Nasir Khusraw]] (1003-1077) the ''[[Itinerarium Cambriae|Journey Through Wales]]'' (1191) and ''[[Descriptio Cambriae|Description of Wales]]'' (1194) by [[Gerald of Wales]], and the travel journals of [[Ibn Jubayr]] (1145–1214) and [[Ibn Battuta]] (1304–1377), both of whom recorded their travels across the known world in detail. The travel genre was a fairly common genre in medieval [[Arabic literature]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Il Milione'', ''[[The Travels of Marco Polo]]'', describing [[Marco Polo]]'s travels through [[Asia]] between 1271 and 1295 is a [[classic books|classic]] of travel literature. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Travel literature became popular during the [[Song dynasty]] (960–1279) of medieval China. The genre was called 'travel record literature' (遊記文學 yóujì wénxué), and was often written in [[narrative]], [[prose]], [[essay]] and [[diary]] style. Travel literature authors such as [[Fan Chengda]] (1126–1193) and [[Xu Xiake]] (1587–1641) incorporated a wealth of [[geographical]] and [[topographical]] information into their writing, while the 'daytrip essay' ''[[Su Shi#Travel record literature|Record of Stone Bell Mountain]]'' by the noted poet and statesman [[Su Shi]] (1037–1101) presented a philosophical and moral argument as its central purpose. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One of the earliest known records of taking pleasure in travel, of travelling for the sake of travel and writing about it, is [[Francesco Petrarch|Petrarch]]'s (1304–1374) ascent of [[Mount Ventoux]] in 1336. He states that he went to the mountaintop for the pleasure of seeing the top of the famous height. His companions who stayed at the bottom he called ''frigida incuriositas'' ("a cold lack of curiosity"). He then wrote about his climb, making [[Medieval allegory|allegorical]] comparisons between climbing the mountain and his own moral progress in life. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Michault Taillevent, a poet for the [[Duke of Burgundy]], travelled through the [[Jura Mountains]] in 1430 and recorded his personal reflections, his horrified reaction to the sheer rock faces, and the terrifying thunderous cascades of mountain streams. [[Antoine de la Sale]] (c. 1388–c. 1462), author of ''Petit Jehan de Saintre'', climbed to the crater of a volcano in the [[Lipari Islands]] in 1407, leaving us with his impressions. "Councils of mad youth" were his stated reasons for going. In the mid-15th century, Gilles le Bouvier, in his ''Livre de la description des pays'', gave us his reason to travel and write: | ||

| + | :Because many people of diverse nations and countries delight and take pleasure, as I have done in times past, in seeing the world and things therein, and also because many wish to know without going there, and others wish to see, go, and travel, I have begun this little book. | ||

| + | |||

| + | By the 16th century accounts to travels to India and Persia had become common enough that they had been compiled into collections such as the ''[[Novus Orbis]]'' ("''New World''") by [[Simon Grynaeus]], and collections by [[Ramusio]] and [[Richard Hakluyt]]. In 1589, Hakluyt (c. 1552–1616) published ''Voyages''. 16th century travelers to Persia included the brothers [[Robert Shirley]] and [[Anthony Shirley]], and for India [[Duarte Barbosa]], [[Ralph Fitch]], [[Ludovico di Varthema]], [[Cesare Federici]], and [[Jan Huyghen van Linschoten]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the 18th century, travel literature was commonly known as the book of travels, which mainly consisted of maritime [[diary|diaries]]. In 18th-century Britain, almost every famous writer worked in the travel literature form. Captain [[James Cook]]'s diaries (1784) were the equivalent of today's best-sellers. [[Alexander von Humboldt]]'s ''Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America, during the years 1799–1804'', originally published in French, was translated to multiple languages and influenced later naturalists, including [[Charles Darwin]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other later examples of travel literature include accounts of the [[Grand Tour]]. Aristocrats, clergy, and others with money and leisure time travelled Europe to learn about the art and architecture of its past. One tourism literature pioneer was [[Robert Louis Stevenson]] (1850–1894) with ''[[An Inland Voyage]]'' (1878), and ''[[Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes]]'' (1879), about his travels in the [[Cévennes]] (France), is among the first popular books to present hiking and camping as recreational activities, and tells of commissioning one of the first [[sleeping bag]]s. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Other notable writers of travel literature in the 19th century include the Russian [[Ivan Goncharov]], who wrote about his experience of a tour around the world in ''[[Frigate "Pallada"]]'' (1858), and [[Lafcadio Hearn]], who interpreted the culture of [[Japan]] with insight and sensitivity. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The 20th century's [[interwar period]] has been described as a heyday of travel literature when many established writers such as [[Graham Greene]], [[Robert Byron]], [[Rebecca West]], [[Freya Stark]], [[Peter Fleming (writer)|Peter Fleming]] and [[Evelyn Waugh]] were traveling and writing notable travel books. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the late 20th century there was a surge in popularity of travel writing, particularly in the English-speaking world with writers such as [[Bruce Chatwin]], [[Paul Theroux]], [[Jonathan Raban]], [[Colin Thubron]], and others. While travel writing previously had mainly attracted interest by historians and biographers, critical studies of travel literature now also developed into an academic discipline in its own right. | ||

| ==Notable travel writers and travel literature == | ==Notable travel writers and travel literature == | ||

| Line 16: | Line 53: | ||

| *[[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]] (Second century [[Common Era|CE]]): | *[[Pausanias (geographer)|Pausanias]] (Second century [[Common Era|CE]]): | ||

| *:''[[Description of Greece]]'' | *:''[[Description of Greece]]'' | ||

| - | *[[Decimus Magnus Ausonius]] (310{{ndash}}394 [[Common Era|CE]]): | + | *[[Decimus Magnus Ausonius]] (310 - 394 [[Common Era|CE]]): |

| *:''Mosella'' (''The Moselle'') — Describes the poet's trip to the banks of the river Moselle, then in Gaul. | *:''Mosella'' (''The Moselle'') — Describes the poet's trip to the banks of the river Moselle, then in Gaul. | ||

| *[[Rutilius Claudius Namatianus]] (Fl. Fifth century [[Common Era|CE]]): | *[[Rutilius Claudius Namatianus]] (Fl. Fifth century [[Common Era|CE]]): | ||

| Line 68: | Line 105: | ||

| *:''Gleanings in Europe: England'' (1837) | *:''Gleanings in Europe: England'' (1837) | ||

| *[[Heinrich Heine]] (1797–1856) | *[[Heinrich Heine]] (1797–1856) | ||

| - | *:''Reisebilder'' (1826-33), ''Harzreise'' (1853) | + | *:''[[Reisebilder]]'' (1826-33), ''[[Harzreise]]'' (1853) |

| *[[Rifa'a el-Tahtawi]], Egyptian traveler to France | *[[Rifa'a el-Tahtawi]], Egyptian traveler to France | ||

| *:''Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz'' (1834) | *:''Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz'' (1834) | ||

| Line 170: | Line 207: | ||

| *[[Wilfred Thesiger]] (1910–2003) | *[[Wilfred Thesiger]] (1910–2003) | ||

| *[[Lawrence Durrell]] (1912–1990): | *[[Lawrence Durrell]] (1912–1990): | ||

| - | *:''Prospero's Cell: A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra'' (1945) — This text describes [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]]'s time in [[Corfu]]. It should be read in tandem with his brother [[Gerald Durrell|Gerald]]'s ''[[My Family and Other Animals]]''. | + | *:''[[Prospero's Cell: A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra]]'' (1945) — This text describes [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]]'s time in [[Corfu]]. It should be read in tandem with his brother [[Gerald Durrell|Gerald]]'s ''[[My Family and Other Animals]]''. |

| *:''Reflections on a Marine Venus'' (1953) — [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]]'s experiences in [[Rhodes]]. | *:''Reflections on a Marine Venus'' (1953) — [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]]'s experiences in [[Rhodes]]. | ||

| *:''Bitter Lemons'' (1957) — [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]] in [[Cyprus]]. | *:''Bitter Lemons'' (1957) — [[Lawrence Durrell|Durrell]] in [[Cyprus]]. | ||

| Line 317: | Line 354: | ||

| *[[Travel writing]] | *[[Travel writing]] | ||

| *[[Travelogue]] | *[[Travelogue]] | ||

| - | *[[Picador Travel Classics]] | + | *[[Travel guide]] |

| - | + | *[[Murray]] | |

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

"The Alps […] fill the mind with an agreeable kind of horror."--Remarks on Several Parts of Italy (1705) by Joseph Addison "It is a curious fact that of that class of literature to which Munchausen belongs, that namely of _Voyages Imaginaires_, the three great types should have all been created in England. Utopia, Robinson Crusoe, and Gulliver, illustrating respectively the philosophical, the edifying, and the satirical type of fictitious travel, were all written in England, and at the end of the eighteenth century a fourth type, the fantastically mendacious, was evolved in this country."--1895 edition of Baron Munchausen "A little beyond this, we got into a sea, not of water, but of milk; and upon it we saw an island full of vines; this whole island was one compact well-made cheese ... The vines have grapes upon them, which yield not wine, but milk." --A True Story (2nd century) by Lucian "You have no need to have read Payne Knight, or Louis Viardot, or John Ruskin, to be able to understand Mont Blanc. The Grands Mulets and the Mer de Glace would interest the merest clodhopper. This is the reason why Switzerland is with travellers an universal favourite. You can’t wrangle about the conflict of styles in a precipice; the odium theologicum has nothing to lay hold of in an avalanche."--Rome and Venice: With Other Wanderings in Italy, in 1866-7 (1869) by George Augustus Sala |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Travel literature is travel writing considered to have value as literature. Travel literature typically records the people, events, sights and feelings of an author who is touring a foreign place for the pleasure of travel. An individual work is sometimes called a travelogue or itinerary.

To be called literature the work must have a coherent narrative, or insights and value, beyond a mere logging of dates and events, such as diary or ship's log. Literature that recounts adventure, exploration and conquest is often grouped under travel literature, but it also has its own genre outdoor literature; these genres will often overlap with no definite boundaries. This article focuses on literature that is more akin to tourism.

Contents |

Fiction

Fictional travelogues make up a large proportion of travel literature. Although it may be desirable in some contexts to distinguish fictional from non-fictional works, such distinctions have proved notoriously difficult to make in practice, as in the famous instance of the travel writings of Marco Polo or John Mandeville. Many "fictional" works of travel literature are based on factual journeys – Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and presumably, Homer's Odyssey (c. 8th century BCE) – while other works, though based on imaginary and even highly fantastic journeys – Dante's Divine Comedy, Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, Voltaire's Candide or Samuel Johnson's The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia – nevertheless contain factual elements.

Jack Kerouac's On the Road (1957) and The Dharma Bums (1958) are fictionalized accounts of his travels across the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s.

History

Early examples of travel literature include Pausanias' Description of Greece in the 2nd century CE, Safarnama (book of Travels) of Nasir Khusraw (1003-1077) the Journey Through Wales (1191) and Description of Wales (1194) by Gerald of Wales, and the travel journals of Ibn Jubayr (1145–1214) and Ibn Battuta (1304–1377), both of whom recorded their travels across the known world in detail. The travel genre was a fairly common genre in medieval Arabic literature.

Il Milione, The Travels of Marco Polo, describing Marco Polo's travels through Asia between 1271 and 1295 is a classic of travel literature.

Travel literature became popular during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of medieval China. The genre was called 'travel record literature' (遊記文學 yóujì wénxué), and was often written in narrative, prose, essay and diary style. Travel literature authors such as Fan Chengda (1126–1193) and Xu Xiake (1587–1641) incorporated a wealth of geographical and topographical information into their writing, while the 'daytrip essay' Record of Stone Bell Mountain by the noted poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101) presented a philosophical and moral argument as its central purpose.

One of the earliest known records of taking pleasure in travel, of travelling for the sake of travel and writing about it, is Petrarch's (1304–1374) ascent of Mount Ventoux in 1336. He states that he went to the mountaintop for the pleasure of seeing the top of the famous height. His companions who stayed at the bottom he called frigida incuriositas ("a cold lack of curiosity"). He then wrote about his climb, making allegorical comparisons between climbing the mountain and his own moral progress in life.

Michault Taillevent, a poet for the Duke of Burgundy, travelled through the Jura Mountains in 1430 and recorded his personal reflections, his horrified reaction to the sheer rock faces, and the terrifying thunderous cascades of mountain streams. Antoine de la Sale (c. 1388–c. 1462), author of Petit Jehan de Saintre, climbed to the crater of a volcano in the Lipari Islands in 1407, leaving us with his impressions. "Councils of mad youth" were his stated reasons for going. In the mid-15th century, Gilles le Bouvier, in his Livre de la description des pays, gave us his reason to travel and write:

- Because many people of diverse nations and countries delight and take pleasure, as I have done in times past, in seeing the world and things therein, and also because many wish to know without going there, and others wish to see, go, and travel, I have begun this little book.

By the 16th century accounts to travels to India and Persia had become common enough that they had been compiled into collections such as the Novus Orbis ("New World") by Simon Grynaeus, and collections by Ramusio and Richard Hakluyt. In 1589, Hakluyt (c. 1552–1616) published Voyages. 16th century travelers to Persia included the brothers Robert Shirley and Anthony Shirley, and for India Duarte Barbosa, Ralph Fitch, Ludovico di Varthema, Cesare Federici, and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten.

In the 18th century, travel literature was commonly known as the book of travels, which mainly consisted of maritime diaries. In 18th-century Britain, almost every famous writer worked in the travel literature form. Captain James Cook's diaries (1784) were the equivalent of today's best-sellers. Alexander von Humboldt's Personal narrative of travels to the equinoctial regions of America, during the years 1799–1804, originally published in French, was translated to multiple languages and influenced later naturalists, including Charles Darwin.

Other later examples of travel literature include accounts of the Grand Tour. Aristocrats, clergy, and others with money and leisure time travelled Europe to learn about the art and architecture of its past. One tourism literature pioneer was Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) with An Inland Voyage (1878), and Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879), about his travels in the Cévennes (France), is among the first popular books to present hiking and camping as recreational activities, and tells of commissioning one of the first sleeping bags.

Other notable writers of travel literature in the 19th century include the Russian Ivan Goncharov, who wrote about his experience of a tour around the world in Frigate "Pallada" (1858), and Lafcadio Hearn, who interpreted the culture of Japan with insight and sensitivity.

The 20th century's interwar period has been described as a heyday of travel literature when many established writers such as Graham Greene, Robert Byron, Rebecca West, Freya Stark, Peter Fleming and Evelyn Waugh were traveling and writing notable travel books.

In the late 20th century there was a surge in popularity of travel writing, particularly in the English-speaking world with writers such as Bruce Chatwin, Paul Theroux, Jonathan Raban, Colin Thubron, and others. While travel writing previously had mainly attracted interest by historians and biographers, critical studies of travel literature now also developed into an academic discipline in its own right.

Notable travel writers and travel literature

- Homer(ca. 8th century BC)

- Lucian of Samosata (c. A.D. 125 – after A.D. 180)

- True History — documents a fantastic voyage that parodies many mythical travels recounted by other authors, such as Homer; considered to be among the first works of Science Fiction.

- Pausanias (Second century CE):

- Decimus Magnus Ausonius (310 - 394 CE):

- Mosella (The Moselle) — Describes the poet's trip to the banks of the river Moselle, then in Gaul.

- Rutilius Claudius Namatianus (Fl. Fifth century CE):

- De reditu suo (Concerning His Return) — The poet describes his voyage along the Mediterranean seacoast from Rome to Gaul circa 416.

- Xuanzang (602 Template:Ndash 664)

- Great Tang Records on the Western Regions — narrative of the Buddhist monk's journey from China to India.

- Ennin (794 Template:Ndash 864), Japanese Buddhist monk who chronicled his travels in Tang China

- Nasir Khusraw (1004 Template:Ndash 1088), Persian traveler in the Middle East:

- Abu ad-Din al-Husayn Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Jubayr (1145Template:Ndash 1217):

- The Travels of Ibn Jubayr

- Gerald of Wales (1146 Template:Ndash 1223)

- Itinerarium Cambriae (Journey Through Wales)

- Marco Polo (1254Template:Ndash 1324 or 1325), Venetian traveller to China and the Mongol Empire in the 13th century:

- Il Milione (1298)

- Ibn Battuta (1304Template:Ndash 1368 or 1369), Moroccan world traveler in the 14th century:

- Rihla (1355)Template:Mdash literally entitled: "A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling"

- Fernão Mendes Pinto (1509-1583), Portuguese explorer and writer:

- Pilgrimage (1614)Template:Mdash memoir of his travels in the Middle and Far East, Ethiopia, Arabian Sea, India and Japan, as one of the first Europeans to reach it in 1542.

- Richard Hakluyt (c. 1552–1616):

- The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (1589) — A foundational text of the travel literature genre

- Evliya Çelebi, (1610-1683)

- François de La Boullaye-Le Gouz (1623–1668):

- Les voyages et observations du sieur de La Boullaye Le gouz (1653 & 1657) — One of the very first true travel books.

- Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694)

- Jonathan Swift (1667-1745)

- Gulliver's Travels

- The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches

- Samuel Johnson (1709–1784):

- A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland (1775) — The lexicographer and his friend James Boswell (1740–1795) visit Scotland in 1773.

- Laurence Sterne (1713–1768):

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1743Template:Ndash 1832):

- Italienische Reise (1816/1817)

- Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826)

- Travel Journals — Record of Jefferson's travels in France, Holland, Germany and Italy, 1784-89, included in his Complete Works with selected portions in various collections of his writings

- Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797):

- A Short Residence in Sweden (1796)

- Johann Gottfried Seume (1763–1810):

- Spaziergang nach Syrakus (1803)

- Jippensha Ikku (1765–1831)

- Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige (The Shank's Mare)Template:Mdash one of the most famous of the Edo period michiyuki (journey) novels

- John Quincy Adams (1767–1848)

- Letters on Silesia: Written During a Tour Through That Country in the Years 1800, 1801 (1804)

- James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851)

- Gleanings in Europe: Switzerland (1836)

- Gleanings in Europe: The Rhine (1836)

- Gleanings in Europe: England (1837)

- Heinrich Heine (1797–1856)

- Reisebilder (1826-33), Harzreise (1853)

- Rifa'a el-Tahtawi, Egyptian traveler to France

- Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz (1834)

- Karl Baedeker (1801–1859)

- George Borrow (1803–1881):

- The Bible in Spain (1843)

- Wild Wales (1862)

- Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859)

- Alexander Kinglake (1809-1891)

- Eothen (1844)

- Charles Dickens (1812–1870):

- American Notes (1842).

- Pictures from Italy (1844–1845).

- Herman Melville (1819–1891):

- Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846).

- Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847) — Chronicles of Melville's experiences as a sailor in Polynesia.

- Fran Levstik (1831–1887):

- Popotovanje od Litije do Čateža (1858) — A journey from Litija to Čatež that includes a very influential Slovenian literary programme.

- William Morris (1834–1896):

- Icelandic Journals (1911)

- Mark Twain (1835–1910):

- The Innocents Abroad (1869)

- Roughing It (1872)

- A Tramp Abroad (1880)

- Following the Equator (1897)

- William Dean Howells (1837–1920)

- Certain Delightful English Towns (1906)

- Henry James (1843–1916)

- A Little Tour in France (1884)

- English Hours (1905)

- The American Scene (1907)

- Italian Hours (1909)

- Octave Mirbeau (1848–1917)

- La 628-E8 (1908)

- Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894):

- An Inland Voyage (1878)

- Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes (1879)

- The Silverado Squatters (1883)

- Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919)

- Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail (1888)

- Through the Brazilian Wilderness (1914)

- Prince Bojidar Karageorgevitch (1862–1908):

- Enchanted India (1898)

- Jelena Dimitrijević (1862–1945):

- Letters from Niš Regarding Harems (1897)

- Letters from Salonica on Young Turk Revolution (1918)

- Letters from India (1928)

- Letters from Egypt (1929)

- The New World, alias: In America for a Year (1934).

- Mary Kingsley (1862Template:Ndash 1900):

- Travels in West Africa (1897).

- J. Smeaton Chase (1864–1923)

- Yosemite Trails (1911)

- California Coast Trails (1913)

- California Desert Trails (1919)

- Joshua Slocum (1844Template:Ndash1909):

- Norman Douglas (1868–1962):

- Old Calabria (1915).

- Ernest Peixotto (1869–1940):

- Our Hispanic Southwest (1916) — Contains the first usage of the ethnic slur "spic"

- Hilaire Belloc (1870–1953):

- The Path To Rome (1902) — A ramble by foot from central France to Rome in 1901.

- W. Somerset Maugham (1874–1965):

- On a Chinese Screen (1922) — Vignettes of China in the '30s from the master of the short story.

- Yone Noguchi (1875–1947)

- Isidora Sekulić (1877–1958):

- Pisma iz Norveške / Letters from Norway (1914)

- D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930):

- Sea and Sardinia (1921).

- Henry Vollam Morton (1892–1979)

- Rebecca West (1892–1983):

- Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941) — A 1,181-page look at Yugoslavia before the tragedies of World War II and the 1990s wars.

- Thomas Raucat (1894–1976)

- L'honorable partie de campagne ("The honorable picnic", 1924)

- De Shang-Haï à Canton ("From Shanghai to Canton", 1927)

- J. Slauerhoff (1898–1936)

- Alleen de havens zijn ons trouw ("Only the Ports Are Loyal to Us", 1992 [1927–1932])

- Peter Aufschnaiter (1899Template:Ndash 1973):

- Eight Years in Tibet (1983)

- Emily Kimbrough (1899–1989) — writer of travel humor.

- And a Right Good Crew (1958)

- Gordon Sinclair (1900–1984):

- Khyber Caravan: Through Kashmir, Waziristan, Afghanistan, Baluchistan and Northern India (1936) — A somewhat curmudgeonly account of 1934 travels in British India by a later famous Canadian journalist and television personality.

- Richard Halliburton (1900–1939), one of the most famous explorers and adventure writers of his generation:

- The Royal Road to Romance, The Flying Carpet, New Worlds to Conquer, The Glorious Adventure, Seven League Boots

- John Steinbeck (1902–1968):

- Travels with Charley: In Search of America (1962) — An American road book describing Steinbeck's journeys with his poodle, Charley.

- Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966):

- Waugh Abroad: Collected Travel Writing — An account of the English novelist's restless wanderings around the world in the 1930s and later.

- Robert Byron (1905–1941):

- The Road to Oxiana (1937) — travels in Persia and Afghanistan

- Laurens van der Post (1906–1996):

- The Lost World of the Kalahari (1958) — Auberon Waugh (1939–2001) described van der Post as the person in whose company he'd most like to spend an evening. This book by the South African soldier/explorer/writer suggests why.

- Robert Heinlein (1907–1988)

- Tramp Royale (1992)

- Ian Fleming (1908–1964):

- Thrilling Cities (1963)

- Paul Bowles (1910–1999)

- Wilfred Thesiger (1910–2003)

- Lawrence Durrell (1912–1990):

- Prospero's Cell: A Guide to the Landscape and Manners of the Island of Corcyra (1945) — This text describes Durrell's time in Corfu. It should be read in tandem with his brother Gerald's My Family and Other Animals.

- Reflections on a Marine Venus (1953) — Durrell's experiences in Rhodes.

- Bitter Lemons (1957) — Durrell in Cyprus.

- Heinrich Harrer (1912–2006)

- Gavin Maxwell (1914–1969)

- Patrick Leigh Fermor (b. 1915):

- A Time Of Gifts (1977) — A journey by an 18 year old in 1933/4 overland from the Hook of Holland to Hungary, rewritten in old age from long lost notes.

- Roger Pilkington (1915–2003) — author of the "Small Boat" series

- Small Boat on the Thames (1966)

- Small Boat on the Moselle (1968)

- Camilo José Cela (1916–2002):

- Viaje a la Alcarria (1948).

- Eric Newby (1919–2006):

- A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush (1958) — Popular English travel writer.

- Lucjan Wolanowski (1920–2006):

- Post to Never-Never Land (Poland, 1968)Template:Mdash reports from Australia;

- Heat and fever (Poland, 1970)Template:Mdash reports from the work in World Health Organization Information department in Geneva, travels in New Delhi, Bangkok and Manila, 1967-1968.

- Gerald Durrell (1925–1995):

- My Family and Other Animals (1956) — A description of an idyllic childhood on Corfu in the 1930s by the brother of Lawrence Durrell (1912–1990). This text combines natural observations, humour, storytelling, and travel.

- Fillets of Plaice (1971).

- Jan Morris (b. 1926):

- Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere (2001) — Author of many works, especially about cities; prior to the 1970s her work was published under her previous name, "James Morris."

- Che Guevara (1928–1967):

- The Motorcycle Diaries (1952)

- Juan Goytisolo (b. 1931)

- Ted Simon (b. 1932):

- Jupiter's Travels (1979)

- Ryszard Kapuściński (1932–2007)

- Another Day of Life (1976)

- The Soccer War (1978)

- The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat (1978)

- Shah of Shahs (1982)

- Imperium (1993)

- The Shadow of the Sun (2001)

- Cees Nooteboom (b. 1933)

- Berlijnse Notities (1990)

- Roads to Santiago (1992)

- Nootebooms Hotel (2002) — Dutch travel writer.

- Barbara Grizzuti Harrison (1934–2002)

- Rubén Caba (b. 1935)

- Por la ruta serrana del Arcipreste (1976, 1977, 1995)

- Venedict Yerofeyev (1938–1990):

- Moskva–Pеtushki (1973) — A Russian tale of alcohol, love, and a train ride; translated into English as Moscow to the End of the Line.

- Peter Mayle (b. 1939)

- Colin Thubron (b. 1939)

- Bruce Chatwin (1940–1989):

- In Patagonia (1977).

- The Songlines (1987) — An English stylist of the 20th century.

- William Least Heat-Moon (b. 1940):

- Blue Highways: A Journey into America (1982)

- Frances Mayes (b. 1940):

- Paul Theroux (b. 1941):

- The Great Railway Bazaar (1975) — Perhaps Theroux's most popular travel work.

- Jonathan Raban (b. 1942)

- Michael Palin (b. 1943)

- Julian Barnes (b. 1946)

- Tom Miller (b. 1947)

- Best Travel Writing 2005, introduction, pp. xvii-xxi, (2005)

- A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration, (2004) pp. 325–343.

- Writing on the Edge: A Borderlands Reader, (ed) (2003)

- Travelers' Tales—Cuba, (ed) (2001)

- Jack Ruby's Kitchen Sink: Offbeat Travels Through America's Southwest, (2000)

- Trading With the Enemy: A Yankee Travels Through Castro's Cuba, (1992)

- The Panama Hat Trail: A Journey From South America, (1986)

- Arizona: The Land and the People, (ed) (1986)

- On the Border: Portraits of America's Southwestern Frontier, (1981)

- Mikirō Sasaki (b. 1947), Japanese

- Chris Stewart (b. 1950)

- Driving Over Lemons: An Optimist in Andalucia (1999)

- A Parrot in the Pepper Tree (2002)

- The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (2007)

- Bill Bryson (b. 1951):

- The Palace Under the Alps (1985) — An early work that is more of a travel guide than a narrative.

- Neither Here Nor There: Travels in Europe (1992)

- Notes from a Small Island (1995) — Travels in the United Kingdom.

- A Walk in the Woods: Rediscovering America on the Appalachian Trail (1999)

- In a Sunburned Country (2001)

- Vikram Seth (b. 1952):

- From Heaven Lake: Travels Through Sinkiang and Tibet (1983)

- Quim Monzó (b. 1952)

- Kenn Kaufman (b. 1954):

- Rory MacLean (b. 1954):

- Stalin’s Nose (1992)

- The Oatmeal Ark (1997)

- Under the Dragon (1998)

- Next Exit Magic Kingdom (2000)

- Falling for Icarus (2004)

- Magic Bus (2006)

- Paul Ruffino (b. 1956)

- Dennison Berwick (b. 1956)

- Savages, The Life and Killing of the Yanomami (1992)

- Amazon (1990)

- A Walk along The Ganges (1986)

- Pico Iyer (b. 1957):

- Video Night in Kathmandu: And Other Reports from the Not-so-Far East (1988),

- Falling off the Map: Some Lonely Places of the World (1993)

- Tropical Classical: Essays from Several Directions (1997),

- Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home (2000) — Three excellent collections of essays on the postmodern experience of travel.

- Tony Horwitz (b. 1959):

- One for the Road: An Outback Adventure (1987)

- Baghdad without a Map and Other Misadventures in Arabia (1991)

- Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War (1998)

- Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before (2002)

- A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World (2008)

- Jeffrey Tayler (b. 1962)

- Siberian Dawn: A Journey Across the New Russia (1999)

- Facing the Congo: A Modern-Day Journey into the Heart of Darkness (2000)

- Glory in a Camel's Eye: Trekking Through the Moroccan Sahara (2003)

- Angry Wind: Through Muslim Black Africa by Truck, Bus, Boat, and Camel (2005)

- River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny (2006)

- Karl Taro Greenfeld (b. 1964):

- Speed Tribes: Days and Nights with Japan's Next Generation (1995),

- Standard Deviations: Growing Up and Coming Down in the New Asia — An exploration of the traveler/backpacker subcultures in the Far East during the 1990s by a writer who was there.

- Christopher Gudgeon (b. 1964):

- Mingling Among The Mongols (1984),

- William Dalrymple (b.1965):

- In Xanadu: A Quest (1989)

- City of Djinns (1992)

- From the Holy Mountain (1994)

- The Age of Kali (1995)

- Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India (2009)

- Tahir Shah (b. 1966):

- Sorcerer's Apprentice

- In Search of King Solomon's Mines

- Trail of Feathers

- The Caliph's House

- In Arabian Nights

- House of the Tiger King

- Beyond the Devil's Teeth

- J. Maarten Troost (b. 1969):

- Gary Arndt (b. 1969):

- Everything Everywhere (2007-2008)

- Cleo Paskal

- Kira Salak (b. 1971)

- Four Corners: A Journey into the Heart of Papua New Guinea (2001)

- The Cruelest Journey: 600 Miles to Timbuktu (2004)

- Tom Bissell (b. 1974)

- Chasing the Sea: Lost Among the Ghosts of Empire in Central Asia (2003)

See also