Unreliable narrator

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

In literature and film, an unreliable narrator (a term coined by Wayne C. Booth in his 1961 book The Rhetoric of Fiction) is a literary device in which the credibility of the narrator is seriously compromised. This unreliability can be due to psychological instability, a powerful bias, a lack of knowledge or even a deliberate attempt to deceive the reader or audience. Unreliable narrators are usually first-person narrators, but third-person narrators can also be unreliable.

The nature of the narrator is sometimes immediately clear. For instance, a story may open with the narrator making a plainly false or delusional claim or admitting to being severely mentally ill, or the story itself may have a frame in which the narrator appears as a character, with clues to his unreliability. A more common, and dramatic, use of the device delays the revelation until near the story's end. This twist ending forces the reader to reconsider their point of view and experience of the story. In many cases the narrator's unreliability is never fully revealed but only hinted at, leaving the reader to wonder how much the narrator should be trusted and how the story should be interpreted.

The literary device of the unreliable narrator should not be confused with other devices such as euphemism, hyperbole, irony, metaphor, pathetic fallacy, personification, sarcasm, or satire, in which the narrator is credible, but the narrator's words cannot be taken literally. Similarly, historical novels, speculative fiction, and clearly delineated dream sequences are generally not considered instances of unreliable narration, even though they describe events that did not or could not happen.

Contents |

Overview

Classification

Attempts have been made at a classification of unreliable narrators. William Riggan analysed in his study discernible types of unreliable narrators, focusing on the first-person narrator as this is the most common kind of unreliable narration. Adapted from his findings is the following list:

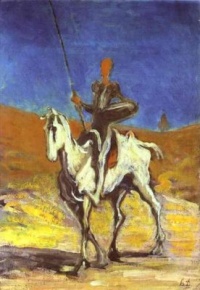

- The Pícaro: a narrator who is characterized by exaggeration and boasting, the first example probably being the soldier in Plautus's comedy Miles Gloriosus.

- Examples in modern literature are Moll Flanders or Simplicius Simplicissimus.

- The Madman: A narrator who is either only experiencing mental defense mechanisms, such as (post-traumatic) dissociation and self-alienation, or severe mental illness, such as schizophrenia or paranoia.

- Examples include several of Edgar Allan Poe's narrators, Franz Kafka's self-alienating narrators, noir fiction and hardboiled fiction's "tough" (cynical) narrator who unreliably describes his own emotions, Barbara Covett in Notes on a Scandal, and Patrick Bateman in American Psycho.

- The Clown: A narrator who does not take narrations seriously and consciously plays with conventions, truth and the reader's expectations.

- Examples of the type include Tristram Shandy and Bras Cubas.

- The Naïf: A narrator whose perception is immature or limited through his or her point of view.

- Examples of naïves include Huckleberry Finn, Holden Caulfield, and Forrest Gump

- The Liar: A mature narrator of sound cognition who deliberately misrepresents himself, often to obscure his unseemly or discreditable past conduct.

- John Dowell in Ford Madox Ford's The Good Soldier exemplifies this kind of narrator.

This typology is surely not exhaustive and cannot claim to cover the whole spectrum of unreliable narration in its entirety or even only the first-person narrator. Further research in this area has been called for.

It also still remains a matter of debate whether and how a non-first-person narrator can be unreliable, though the deliberate restriction of information to the audience—for example in the three interweaving plays in Alan Ayckbourn's The Norman Conquests, each of which shows the action taking place only in one of three locations during the course of a weekend—can provide instances of unreliable narrative, even if not necessarily of an unreliable narrator.

Definitions and theoretical approaches

Wayne C. Booth was the earliest who formulated a reader-centered approach to unreliable narration and distinguished between a reliable and unreliable narrator on the grounds of whether the narrator's speech violates or conforms with general norms and values. He writes, "I have called a narrator reliable when he speaks for or acts in accordance with the norms of the work (which is to say the implied author's norms), unreliable when he does not." Peter J. Rabinowitz criticized Booth's definition for relying too much on the extradiegetic facts such as norms and ethics, which must necessarily be tainted by personal opinion. He consequently modified the approach to unreliable narration.

- There are unreliable narrators (c.f. Booth). An unreliable narrator however, is not simply a narrator who 'does not tell the truth' – what fictional narrator ever tells the literal truth? Rather an unreliable narrator is one who tells lies, conceals information, misjudges with respect to the narrative audience – that is, one whose statements are untrue not by the standards of the real world or of the authorial audience but by the standards of his own narrative audience. […] In other words, all fictional narrators are false in that they are imitations. But some are imitations who tell the truth, some of people who lie.

Rabinowitz' main focus is the status of fictional discourse in opposition to factuality. He debates the issues of truth in fiction, bringing forward four types of audience who serve as receptors of any given literary work:

- "Actual audience" (= the flesh-and-blood people who read the book)

- "Authorial audience" (= hypothetical audience to whom the author addresses his text)

- "Narrative audience" (= imitation audience which also possesses particular knowledge)

- "Ideal narrative audience" (= uncritical audience who accepts what the author is saying)

Rabinowitz suggests that "In the proper reading of a novel, then, events which are portrayed must be treated as both 'true' and 'untrue' at the same time. Although there are many ways to understand this duality, I propose to analyze the four audiences which it generates." Similarly, Tamar Yacobi has proposed a model of five criteria ('integrating mechanisms') which determine if a narrator is unreliable. Instead of relying on the device of the implied author and a text-centered analysis of unreliable narration, Ansgar Nünning gives evidence that narrative unreliability can be reconceptualized in the context of frame theory and of readers' cognitive strategies.

- […] to determine a narrator's unreliability one need not rely merely on intuitive judgments. It is neither the reader's intuitions nor the implied author's norms and values that provide the clue to a narrator's unreliability, but a broad range of definable signals. These include both textual data and the reader's preexisting conceptual knowledge of the world. In sum whether a narrator is called unreliable or not does not depend on the distance between the norms and values of the narrator and those of the implied author but between the distance that separates the narrator's view of the world from the reader's world-model and standards of normality.

Unreliable Narration in this view becomes purely a reader's strategy of making sense of a text, i.e. of reconciling discrepancies in the narrator's account (cf. signals of unreliable narration). Nünning thus effectively eliminates the reliance on value judgments and moral codes which are always tainted by personal outlook and taste. Greta Olson recently debated both Nünning's and Booth's models, revealing discrepancies in their respective views.

- […] Booth's text-immanent model of narrator unreliability has been criticized by Ansgar Nünning for disregarding the reader's role in the perception of reliability and for relying on the insufficiently defined concept of the implied author. Nünning updates Booth's work with a cognitive theory of unreliability that rests on the reader's values and her sense that a discrepancy exists between the narrator's statements and perceptions and other information given by the text.

and offers "[…] an update of Booth's model by making his implicit differentiation between fallible and untrustworthy narrators explicit." Olson then argues "[…] that these two types of narrators elicit different responses in readers and are best described using scales for fallibility and untrustworthiness." She proffers that all fictional texts that employ the device of unreliability can best be considered along a spectrum of fallibility that begins with trustworthiness and ends with unreliability. This model allows for all shades of grey in between the poles of trustworthiness and unreliability. It is consequently up to each individual reader to determine the credibility of a narrator in a fictional text.

Signals of unreliable narration

Whichever definition of unreliability one follows, there are a number of signs that constitute or at least hint at a narrator's unreliability. Nünning has suggested to divide these signals into three broad categories.

- Intratextual signs such as the narrator contradicting himself, having gaps in memory, or lying to other characters

- Extratextual signs such as contradicting the reader's general world knowledge or impossibilities (within the parameters of logic)

- Reader's Literary Competence. This includes the reader's knowledge about literary types (e.g. stock characters that reappear over centuries), knowledge about literary genres and its conventions or stylistic devices

Examples

Historical occurrences

One of the earliest uses of unreliability in literature is in The Frogs by Aristophanes. After the God Dionysus claims to have sunk 12 or 13 enemy ships with Cleisthenes (son of Sibyrtius), his slave Xanthias says "Then I woke up." A more well-known version is in Plautus' comedy Miles Gloriosus (3rd–2nd centuries BC), which features a soldier who constantly embellishes his accomplishments while his slave Artotrogus, in asides, claims the stories are untrue and he is only backing them up to get fed. The literary device of the "unreliable narrator" was used in several medieval fictional Arabic tales of the One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights. In one tale, "The Seven Viziers", a courtesan accuses a king's son of having assaulted her, when in reality she had failed to seduce him. Seven viziers attempt to save his life by narrating seven stories to prove the unreliability of the courtesan, and the courtesan responds by narrating a story to prove the unreliability of the viziers. The unreliable narrator device is also used to generate suspense in another Arabian Nights tale, "The Three Apples", an early murder mystery. At one point of the story, two men claim to be the murderer, one of whom is revealed to be lying. At another point in the story, in a flashback showing the reasons for the murder, it is revealed that an unreliable narrator convinced the man of his wife's infidelity, thus leading to her murder.

Another early example of unreliable narration is Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. In "The Merchant's Tale" for example, the narrator, being unhappy in his marriage, allows his misogynistic bias to slant much of his tale. In The Wife of Bath, the Wife often makes inaccurate quotations and incorrectly remembers stories.

Novels

A controversial example of an unreliable narrator occurs in Agatha Christie's novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, where the narrator hides essential truths in the text (mainly through evasion, omission, and obfuscation) without ever overtly lying. Many readers at the time felt that the plot twist at the climax of the novel was nevertheless unfair. Christie used the concept again in her 1967 novel Endless Night. Similar unreliable narrators often appear in detective novels and thrillers, where even a first-person narrator might hide essential information and deliberately mislead the reader in order to preserve the surprise ending. In some cases, the narrator describes himself or herself as doing things which seem questionable or discreditable, only to reveal in the end that such actions were not what they seemed (e.g. Alistair MacLean's "The Golden Rendezvous" and John Grisham's "The Racketeer").

Many novels are narrated by children, whose inexperience can impair their judgment and make them unreliable. In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Huck's innocence leads him to make overly charitable judgments about the characters in the novel.

Ken Kesey's two most famous novels feature unreliable narrators. "Chief" Bromden in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest suffers from schizophrenia, and his telling of the events often includes things such as people growing or shrinking, walls oozing with slime, or the orderlies kidnapping and "curing" Santa Claus. Narration in Sometimes a Great Notion switches between several of the main characters, whose bias tends to switch the reader's sympathies from one person to another, especially in the rivalry between main character Leland and Hank Stamper. Many of Susan Howatch's novels similarly use this technique; each chapter is narrated by a different character, and only after reading chapters by each of the narrators does the reader realize each of the narrators has biases and "blind spots" that cause him or her to perceive shared experiences differently.

Humbert Humbert, the main character and narrator of Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita, often tells the story in such a way as to justify his pedophilic fixation on young girls, in particular his sexual relationship with his 12-year-old stepdaughter. Similarly, the narrator of A. M. Homes' The End of Alice deliberately withholds the full story of the crime that put him in prison—the rape and subsequent murder of a young girl—until the end of the novel.

In some instances, unreliable narration can bring about the fantastic in works of fiction. In Kingsley Amis' The Green Man, for example, the unreliability of the narrator Maurice Allington destabilizes the boundaries between reality and the fantastic. The same applies to Nigel Williams's Witchcraft. An Instance of the Fingerpost by Iain Pears also employs several points of view from narrators whose accounts are found to be unreliable and in conflict with each other.

Zeno Cosini, the narrator of Italo Svevo's Zeno's Conscience, is a typical example of unreliable narrator: in fact the novel is presented as a diary of Zeno himself, who unintentionally distorts the facts to justify his faults. His psychiatrist, who publishes the diary, claims in the introduction that it's a mix of truths and lies.

Films

One of the earliest examples of the use of an unreliable narrator in film is the German expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, from 1920. In this film, an epilogue to the main story is a twist ending revealing that Francis, through whose eyes we see the action, is a patient in an insane asylum, and the flashback which forms the majority of the film is simply his mental delusion.

The 1945 film noir Detour is told from the perspective of an unreliable protagonist who may be trying to justify his actions.

In Possessed (1947), Joan Crawford plays a woman who is taken to a psychiatric hospital in a state of shock. She gradually tells the story of how she came to be there to her doctors, which is related to the audience in flashbacks, some of which are later revealed to be hallucinations or distorted by paranoia.

In Rashômon (1950), a Japanese crime drama film directed by Akira Kurosawa, adapted from "In a Grove" (1921), uses multiple narrators to tell the story of the death of a samurai. Each of the witnesses describe the same basic events but differ wildly in the details, alternately claiming that the samurai died by accident, suicide, or murder. The term "Rashômon effect" is used to describe how different witnesses are able to produce differing, yet plausible, accounts of the same event, with equal sincerity. The film does not select the "authentic" narrator from the differing accounts: all versions are equally valid and equally suspect.

The 1950 Alfred Hitchcock film Stage Fright (1950) uses the device of unreliable narration by presenting the aftermath of a murder in a flashback, as told by the murderer. The details of the flashback provide an explanation which helps convince the innocent main protagonist of the film to help the murderer, believing him innocent.

In the movie version of Forrest Gump (1994), the title character narrates his life story, and in the process naïvely refers to Apple Computers as a "fruit company" while also assuming that sustaining a "million dollar wound" meant that one would get paid for it. He also states that Jenny's dad treated her well because "he was always kissing and touching her and her sisters."

The 1995 film The Usual Suspects reveals that the narrator had been deceiving another character, and hence the audience, by inventing stories and characters from whole cloth. The character is seen as a weak, humble, and quiet criminal but it is later found by the audience that he is the fabled crime boss Keyser Soze.

In the 1999 film |Fight Club, it is revealed that the narrator suffers from dissociative identity disorder and that some events were fabricated, which means only one of the two main protagonists actually exists, as the other is in the narrator's mind.

In the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind, it is eventually revealed that the narrator is suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, and many of the events he witnessed occurred only in his own mind.

In the 2013 film The Lone Ranger the narrator, Tonto (Johnny Depp), is identified quickly as potentially unreliable by a child attending a 1930s carnival sideshow during extensive questioning about the events leading to the origin of the wild west character the child emulates. The child is wearing the costume identified with the fictional western hero of radio, comics, films, and television. The events related by the narrator vaguely follow an alternative version of character development that occurred during its radio dramas and the beginning of its television series, but with novel disclosures of graphic details that occur as a series of flashbacks portraying the elderly Tonto's memories of the events. Along with the child, the audience is left to make their own judgments about the memories of Tonto.

Television

In the final episode of M*A*S*H, unreliable narration is used to create dramatic effect; Hawkeye Pierce, now a patient of Sidney Freedman in an army mental hospital ward, recounts a traumatic memory of a recent event. In the recounting a key component is replaced with something more innocuous, leaving the viewer wondering why that incident resulted in his mental illness. Later, psychoanalysis with free-association reveals the true memory, which is much more disturbing and can be clearly seen as the cause.

Comics

In Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's Batman: The Killing Joke, the Joker, who is the villain of the story, reflects on the pitiful life that transformed him into a psychotic murderer. Although the Joker's version of the story is not implausible given overall Joker storyline in the Batman comics, the Joker admits at the end of The Killing Joke that he himself is uncertain if it is true.

Notable works featuring unreliable narrators

Literature

- Martin Amis's Time's Arrow

- Augusto Roa Bastos's I, the Supreme

- Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights

- Angela Carter's Wise Children

- Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales

- Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone

- The works of Bret Easton Ellis, most prominently American Psycho

- Umberto Eco's Baudolino

- William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury

- Ford Madox Ford's The Good Soldier

- Günter Grass's The Tin Drum

- Kazuo Ishiguro's When We Were Orphans

- Henry James's The Turn of the Screw

- Anita Loos's Gentlemen Prefer Blondes

- Vladimir Nabokov's Pale Fire and Lolita

- J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye

- Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children

- William Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon

- Robert Graves's I, Claudius

Film

- Amarcord directed by Federico Fellini

- Big Fish directed by Tim Burton

- The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari directed by Robert Wiene

- Fight Club directed by David Fincher

- Forrest Gump directed by Robert Zemeckis

- Memento directed by Christopher Nolan

- Rashômon directed by Akira Kurosawa

See also