Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

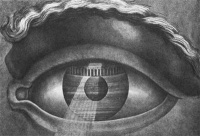

Théatre de Besançon, interior view by Claude Nicolas Ledoux

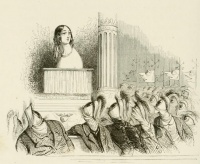

Venus at the Opera (1844) by Grandville

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema is a feminist film essay by British academic Laura Mulvey, written in 1973 and first published in 1975. It elaborates on the male gaze in film and in visual culture in general. Key terms in its vocabulary are lack, castration, fetishism, voyeurism, gaze and scopophilia.

Contents |

Analysis

The first line of the second paragraph sets the tone:

- "The paradox of phallocentrism in all its manifestations is that it depends on the image of the castrated woman to give order and meaning to its world. An idea of woman stands as lynch pin to the system: it is her lack that produces the phallus as a symbolic presence, it is her desire to make good the lack that the phallus signifies. "

Other telling soundbites are:

- "Sadism demands a story, depends on making something happen, forcing a change in another person, a battle of will and strength, victory/defeat."

and

- "The presence of woman is an indispensable element of spectacle in normal narrative film, yet her visual presence tends to work against the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action in moments of erotic contemplation."

Importance

Mulvey's article was one of the first major essays that helped shift the orientation of film theory towards a psychoanalytic framework, influenced by the theories of Sigmund Freud and Jacques Lacan. Prior to Mulvey, film theorists such as Jean-Louis Baudry and Christian Metz had attempted to use psychoanalytic ideas in their theoretical accounts of the cinema, but Mulvey's contribution was to inaugurate the intersection of film theory, psychoanalysis, and feminism.

Rationale

Mulvey's article engaged in no empirical research of film audiences. She instead stated that she intended to make a "political use" of Freud and Lacan, and then used some of their concepts to argue that the cinematic apparatus of classical Hollywood cinema inevitably put the spectator in a masculine subject position, with the figure of the woman on screen as the object of desire. In the era of classical Hollywood cinema, viewers were encouraged to identify with the protagonist of the film, who tended to be a man. Meanwhile, Hollywood female characters of the 1950s and 60s were, according to Mulvey, coded with "to-be-looked-at-ness." Mulvey suggests that there were two distinct modes of the male gaze of this era: "voyeuristic" (i.e. seeing women as 'madonnas') and "fetishistic" (i.e. seeing women as 'whores').

Mulvey argued that the only way to annihilate the "patriarchal" Hollywood system was to radically challenge and re-shape the filmic strategies of classical Hollywood with alternative feminist methods. She called for a new feminist avant-garde filmmaking that would rupture the magic and pleasure of classical Hollywood filmmaking. She wrote, "It is said that analysing pleasure or beauty annihilates it. That is the intention of this article".

Criticism

Radical feminists made a major criticism of "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema". They claimed that, while Mulvey believed that classical Hollywood cinema reflected and shaped the "patriarchal order", the perspective of her writing actually remained within that very heterosexual order. The article was thus said to have contradicted its "radical" claims, by actually being a covert perpetuation of heterosexual patriarchal order. This was because, in her article, Mulvey presupposes the spectator to be a heterosexual man. She was thus felt to be denying the existence of lesbian women and even heterosexual women.

"Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" was the subject of much interdisciplinary discussion among film theorists that continued into the mid 1980s. Critics of the article objected to the fact that her argument implied the impossibility of genuine 'feminine' enjoyment of the classical Hollywood cinema, and to the fact that her argument did not seem to take into account spectatorships that were not organised along the normative lines of gender. For example, a metaphoric 'transvestism' might be possible when viewing a film – a male viewer might enjoy a 'feminine' point-of-view provided by a film, or vice versa; gay, lesbian and bisexual spectatorships might also be different. Her article also did not take into account the findings of the later wave of media audience studies on the complex nature of fan cultures and their interaction with stars. Gay male film theorists such as Richard Dyer have used Mulvey's work as a starting point to explore the complex projections that many gay men fix onto certain female stars (e.g. Liza Minnelli, Greta Garbo, Judy Garland).

Theorists who call for a visceral experience of cinema have criticized the essay for its call for a "destruction of pleasure". Jack Sargeant has called the essay frigid psychoanalytic orthodoxy.

A manifesto

Mulvey later wrote that her article was meant to be a provocation or a manifesto, rather than a reasoned academic article that took all objections into account. She addressed many of her critics, and changed some of her opinions, in a follow-up article, "Afterthoughts on 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema'" (which also appears in the Visual and Other Pleasures collection).

Publication history

The essay was published in 1975 in the influential British film theory journal Screen. It later appeared in a collection of Mulvey's essays entitled Visual and Other Pleasures, and numerous other anthologies.

See also