Cabinet of curiosities

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 19:48, 6 January 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) (→Cabinets de curiosités célèbres) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 23:44, 6 January 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) (→Cabinets de curiosités célèbres) Next diff → |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

| * Il n’y eut pas de collectionneurs de rang aussi éminent au Royaume-Uni. Néanmoins, le baronnet [[Hans Sloane]] (1660-1753), naturaliste, racheta de nombreux cabinets privés et constitua une riche collection de plantes qui fut mise à la disposition de [[John Ray]] avant d’être offerte à la nation afin d’être présentée au public ([[British Museum]], 1759, puis [[Musée d'histoire naturelle de Londres]], 1881). | * Il n’y eut pas de collectionneurs de rang aussi éminent au Royaume-Uni. Néanmoins, le baronnet [[Hans Sloane]] (1660-1753), naturaliste, racheta de nombreux cabinets privés et constitua une riche collection de plantes qui fut mise à la disposition de [[John Ray]] avant d’être offerte à la nation afin d’être présentée au public ([[British Museum]], 1759, puis [[Musée d'histoire naturelle de Londres]], 1881). | ||

| - | [[Edmond Bonnaffé]] note que En effet, à côté des grandes seigneurs de Paris et des villes principales, adorateurs exclusifs du grand art, se formait une armée d'hommes modestes et clairvoyants qui recueillaient, petit à petit, les miettes de la curiosité. C'étaient des médecins, des chanoines, des apothicaires… Sans abandonner tout projet d’éblouir le public par le faste des œuvres d’art présentées ou de l’étonner par la présentation d’objets insolites, voire monstrueux, les propriétaires aux moyens plus modestes constituèrent bien souvent des cabinets d’histoire naturelle qui eurent souvent une influence scientifique, en partie grâce à la publication de leurs catalogues illustrés. | + | *[[Edmond Bonnaffé]] note que En effet, à côté des grandes seigneurs de Paris et des villes principales, adorateurs exclusifs du grand art, se formait une armée d'hommes modestes et clairvoyants qui recueillaient, petit à petit, les miettes de la curiosité. C'étaient des médecins, des chanoines, des apothicaires… Sans abandonner tout projet d’éblouir le public par le faste des œuvres d’art présentées ou de l’étonner par la présentation d’objets insolites, voire monstrueux, les propriétaires aux moyens plus modestes constituèrent bien souvent des cabinets d’histoire naturelle qui eurent souvent une influence scientifique, en partie grâce à la publication de leurs catalogues illustrés. |

| - | Parmi les cabinets contenant des « miettes de curiosités », on peut mentionner : | + | *Parmi les cabinets contenant des « miettes de curiosités », on peut mentionner : |

| * Le fils d’[[André Tiraqueau]], Michel, possédait à Fontenay-le-Comte un cabinet décrit en vers<ref group=alpha>Hymne de Marie Tiraqueau.</ref>, en 1566, par son neveu, [[André de Rivaudeau]], le rival de Ronsard : | * Le fils d’[[André Tiraqueau]], Michel, possédait à Fontenay-le-Comte un cabinet décrit en vers<ref group=alpha>Hymne de Marie Tiraqueau.</ref>, en 1566, par son neveu, [[André de Rivaudeau]], le rival de Ronsard : | ||

| - | {{vers|texte= | + | |

| Mais un autre dira le merveilleux ouvrage | Mais un autre dira le merveilleux ouvrage | ||

| Lequel tu as receu d’Apollon en partage. | Lequel tu as receu d’Apollon en partage. | ||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

| Ou au plus pres du vif il te peint cinq cens plantes, | Ou au plus pres du vif il te peint cinq cens plantes, | ||

| Que dans ton Bel-esbat nees tu luy presentes. | Que dans ton Bel-esbat nees tu luy presentes. | ||

| - | }} | + | |

| - | : Michel Tiraqueau possédait donc un herbier peint de 500 plantes<ref>{{Lien web|langue=fr|auteur=|titre=Cabinet de Tiraqueau, Michel|url=https://curiositas.org/cabinet/curios315|date=|site=curiositas.org|consulté le=2021-12-18}}.</ref>. | + | * Michel Tiraqueau possédait donc un herbier peint de 500 plantes<ref>{{Lien web|langue=fr|auteur=|titre=Cabinet de Tiraqueau, Michel|url=https://curiositas.org/cabinet/curios315|date=|site=curiositas.org|consulté le=2021-12-18}}.</ref>. |

| * [[Bernard Palissy]] posséda un cabinet qu’il mentionne dans sa dédicace au « Sire Anthoine de Ponts » au début de ''Discours admirables de la nature des eaux et fontaines …'' (1580)<ref group=alpha>''Œuvres complètes avec des notes et une notice historique par P. A. Cap'', Paris: Dubochet et Cie, 1844, p. 130 : « Tels liures pernicieux [ceux des alchimistes] m'ont causé gratter le terre l’espace de quarante ans, et foüiller les entrailles d'icelle, à fin de connoistre les choses qu’elle produit dans soy, et par tel moyen i’ay trouué grace deuant Dieu, qui m’a fait connoistre des secrets qui ont esté iusques à present inconnuz aux hommes, voire aux plus doctes, comme l'on pourra connoistre par mes escrits contenuz en ce liure, ie sçay bien qu'aucuns se moqueront, en disant qu’il est impossible qu’vn homme destitué de la langue Latine puisse auoir intelligence des choses naturelles; et diront que c’est à moy vne grande temerité d’escrire contre l'opinion de tant de Philosophes fameux et anciens, lesquels ont escrit des effects naturels, et rempli toute la terre de sagesse. Ie sçay aussi qu’autres iugeront selon l'exterieur, disans que ie ne suis qu'un pauure artisan : et par tels propos voudront faire trouuer mauuais mes escrits. A la verité il y a des choses en mon liure qui seront difficiles à croire aux ignorans. Nonobstant toutes ces considerations, ie n’ay laissé de poursuyure mon entreprise, et pour couper broche à toutes calomnies et embusches, i'ay dressé vn cabinet auquel i’ay mis plusieurs choses admirables et monstrueuses, que i'ay tirees de la matrice de la terre, lesquelles rendent tesmoignage certain de ce que ie dis, et ne se trouuera homme qui ne soit contraint confesser iceux veritables, apres qu’il aura veu les choses que i’ay préparees en mon cabinet, pour rendre certains tous ceux qui ne voudroyent autrement adiouster foy à mes escrits. S'il venoit d’auenture quelque grosse teste, qui voulut ignorer les preuues mises en mon cabinet, ie ne demanderois autre iugement que le vostre, lequel est suffisant pour conuaincre et renuerser toutes les opinions de ceux qui y voudroyent contredire. » | * [[Bernard Palissy]] posséda un cabinet qu’il mentionne dans sa dédicace au « Sire Anthoine de Ponts » au début de ''Discours admirables de la nature des eaux et fontaines …'' (1580)<ref group=alpha>''Œuvres complètes avec des notes et une notice historique par P. A. Cap'', Paris: Dubochet et Cie, 1844, p. 130 : « Tels liures pernicieux [ceux des alchimistes] m'ont causé gratter le terre l’espace de quarante ans, et foüiller les entrailles d'icelle, à fin de connoistre les choses qu’elle produit dans soy, et par tel moyen i’ay trouué grace deuant Dieu, qui m’a fait connoistre des secrets qui ont esté iusques à present inconnuz aux hommes, voire aux plus doctes, comme l'on pourra connoistre par mes escrits contenuz en ce liure, ie sçay bien qu'aucuns se moqueront, en disant qu’il est impossible qu’vn homme destitué de la langue Latine puisse auoir intelligence des choses naturelles; et diront que c’est à moy vne grande temerité d’escrire contre l'opinion de tant de Philosophes fameux et anciens, lesquels ont escrit des effects naturels, et rempli toute la terre de sagesse. Ie sçay aussi qu’autres iugeront selon l'exterieur, disans que ie ne suis qu'un pauure artisan : et par tels propos voudront faire trouuer mauuais mes escrits. A la verité il y a des choses en mon liure qui seront difficiles à croire aux ignorans. Nonobstant toutes ces considerations, ie n’ay laissé de poursuyure mon entreprise, et pour couper broche à toutes calomnies et embusches, i'ay dressé vn cabinet auquel i’ay mis plusieurs choses admirables et monstrueuses, que i'ay tirees de la matrice de la terre, lesquelles rendent tesmoignage certain de ce que ie dis, et ne se trouuera homme qui ne soit contraint confesser iceux veritables, apres qu’il aura veu les choses que i’ay préparees en mon cabinet, pour rendre certains tous ceux qui ne voudroyent autrement adiouster foy à mes escrits. S'il venoit d’auenture quelque grosse teste, qui voulut ignorer les preuues mises en mon cabinet, ie ne demanderois autre iugement que le vostre, lequel est suffisant pour conuaincre et renuerser toutes les opinions de ceux qui y voudroyent contredire. » | ||

| - | .</ref> : il l’avait constitué afin de réunir des preuves des faits qu’il défendait au sujet notamment des fossiles, qui étaient, selon lui, des débris d’animaux. On peut noter aussi qu’il oppose son approche en contact direct avec la réalité étudiée à celle des « philosophes » reconnus qui trouvaient leur science dans des livres écrits en latin. | + | |

| + | il l’avait constitué afin de réunir des preuves des faits qu’il défendait au sujet notamment des fossiles, qui étaient, selon lui, des débris d’animaux. On peut noter aussi qu’il oppose son approche en contact direct avec la réalité étudiée à celle des « philosophes » reconnus qui trouvaient leur science dans des livres écrits en latin. | ||

| * [[Paul Contant]]. (1562-1629) possédait un jardin botanique avec un cabinet d’histoire naturelle. En 1609, il publia un poème intitulé Le Jardin, et Cabinet poétique. Il y évoque les plantes qu’il cultive, les plus prisées par les collectionneurs, et chante leurs avantages. En outre, il chante plusieurs animaux qu'il collectionne aussi. Le poème est accompagné de gravures et d’un index. Contant possède en outre de riches herbiers de plantes exotiques. | * [[Paul Contant]]. (1562-1629) possédait un jardin botanique avec un cabinet d’histoire naturelle. En 1609, il publia un poème intitulé Le Jardin, et Cabinet poétique. Il y évoque les plantes qu’il cultive, les plus prisées par les collectionneurs, et chante leurs avantages. En outre, il chante plusieurs animaux qu'il collectionne aussi. Le poème est accompagné de gravures et d’un index. Contant possède en outre de riches herbiers de plantes exotiques. | ||

Revision as of 23:44, 6 January 2022

|

"I had beside me several of the catalogues of the older collections; amongst others those of Ole Worm's museum and of the Copenhagen museum, Grew's Catalogue of the Rarities belonging to the Royal Society, Sibbald's Auctarium Musei Balfouriani, Mercati's Metallotheca, the Museo Cospiano, and Aldrovandi's Museum Metallicum. I often consulted them and found both amusement and instruction in turning over their pages, and it seemed to me that from such sources one could learn something of the idea of what a museum ought to be, which the old collectors had, their schemes of classification and the science on which these were based."--Museums: Their History and Their Use with a Bibliography and List of Museums in the United Kingdom (1904) by David Murray "Those authors who undertake to treat of museums in a thorough and exhaustive manner find in Noah's Ark the most complete Museum of Natural History that the world has ever seen. Coming to later times they make sure that King Solomon had a collection of curiosities; and when King Hezekiah in a boastful mood showed the envoys of the King of Babylon all the house of his precious things, the silver and the gold and the spices and the precious oil and all that was found in his treasures, they are certain that he took them round his museum. Some of these objects of interest were thought to have come down to our times, all duly catalogued by Collin de Plancy."--Museums: Their History and Their Use with a Bibliography and List of Museums in the United Kingdom (1904) by David Murray |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

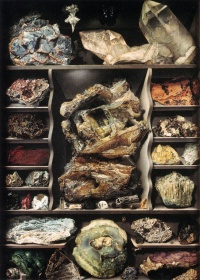

Cabinets of curiosities (also known as Kunstkammer, Wunderkammer, Cabinets of Wonder, or wonder-rooms) were encyclopedic collections of types of objects whose categorical boundaries were, in Renaissance Europe, yet to be defined. Modern terminology would categorize the objects included as belonging to natural history (sometimes faked), geology, ethnography, archaeology, religious or historical relics, works of art (including cabinet paintings) and antiquities. Besides the most famous, best documented cabinets of rulers and aristocrats, members of the merchant class and early practitioners of science in Europe, formed collections that were precursors to museums.

An early book on the subject is Die Kunst- und Wunderkammern der Spätrenaissance (1908) by Julius von Schlosser.

Contents |

History

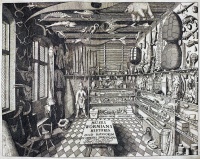

The earliest pictorial record of a natural history cabinet is the engraving in Ferrante Imperato's Dell'Historia Naturale (Naples 1599) (illustration, left). It serves to authenticate its author's credibility as a source of natural history information, in showing his open bookcases at the right, in which many volumes are stored lying down and stacked, in the medieval fashion, or with their spines upward, to protect the pages from dust. Some of the volumes doubtless represent his herbarium. Every surface of the vaulted ceiling is occupied with preserved fishes, stuffed mammals and curious shells, with a stuffed crocodile suspended in the centre. Examples of corals stand on the bookcases. At the left, the room is fitted out like a studiolo with a range of built-in cabinets whose fronts can be unlocked and let down to reveal intricately fitted nests of pigeonholes forming architectural units, filled with small mineral specimens. Above them, stuffed birds stand against panels inlaid with square polished stone samples, doubtless marbles and jaspers or fitted with pigeonhole compartments for specimens. Below them, a range of cupboards contain specimen boxes and covered jars.

In 1587 Gabriel Kaltemarckt advised Christian I of Saxony that three types of item were indispensable in forming a "Kunstkammer" or art collection: firstly sculptures and paintings; secondly "curious items from home or abroad"; and thirdly "antlers, horns, claws, feathers and other things belonging to strange and curious animals". When Albrecht Dürer visited the Netherlands in 1521, apart from artworks he sent back to Nuremberg various animal horns, a piece of coral, some large fish fins and a wooden weapon from the East Indies. The highly characteristic range of interests represented in Frans II Francken's painting of 1636 (illustration, above) shows paintings on the wall that range from landscapes, including a moonlit scene—a genre in itself—to a portrait and a religious picture (the Adoration of the Magi) intermixed with preserved tropical marine fish and a string of carved beads, most likely amber, which is both precious and a natural curiosity. Sculpture both classical and secular (the sacrificing Libera, a Roman fertility goddess) on the one hand and modern and religious (Christ at the Column) are represented, while on the table are ranged, among the exotic shells (including some tropical ones and a shark's tooth): portrait miniatures, gem-stones mounted with pearls in a curious quatrefoil box, a set of sepia chiaroscuro woodcuts or drawings, and a small still-life painting leaning against a flower-piece, coins and medals—presumably Greek and Roman—and Roman terracotta oil-lamps, a Chinese-style brass lock, curious flasks, and a blue-and-white Ming porcelain bowl.

The Kunstkammer of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor (ruled 1576–1612), housed in the Hradschin at Prague, was unrivalled north of the Alps; it provided a solace and retreat for contemplation that also served to demonstrate his imperial magnificence and power in symbolic arrangement of their display, ceremoniously presented to visiting diplomats and magnates. Rudolf's uncle, Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria, also had a collection, organized by his treasurer, Leopold Heyperger, which put special emphasis on paintings of people with interesting deformities, which remains largely intact as the Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Austria. "The Kunstkammer was regarded as a microcosm or theater of the world, and a memory theater. The Kunstkammer conveyed symbolically the patron's control of the world through its indoor, microscopic reproduction." Of Charles I of England's collection, Peter Thomas states succinctly, "The Kunstkabinett itself was a form of propaganda.".

Two of the most famously described seventeenth-century cabinets were those of Ole Worm, known as Olaus Wormius (1588–1654) (illustration, above right), and Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680). These seventeenth-century cabinets were filled with preserved animals, horns, tusks, skeletons, minerals, as well as other interesting man-made objects: sculptures wondrously old, wondrously fine or wondrously small; clockwork automata; ethnographic specimens from exotic locations. Often they would contain a mix of fact and fiction, including apparently mythical creatures. Worm's collection contained, for example, what he thought was a Scythian Lamb, a woolly fern thought to be a plant/sheep fabulous creature. However he was also responsible for identifying the narwhal's tusk as coming from a whale rather than a unicorn, as most owners of these believed. The specimens displayed were often collected during exploring expeditions and trading voyages.

In the second half of the 18th century, Belsazar Hacquet (c. 1735–1815) operated in Ljubljana, then the capital of Carniola, a natural history cabinet (Template:Lang-de) that was appreciated throughout Europe and was visited by the highest nobility, including the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II, the Russian grand duke Paul and Pope Pius VI, as well as by famous naturalists, such as Francesco Griselini and Franz Benedikt Hermann. It included a number of minerals, including specimens of mercury from the Idrija mine, a herbarium vivum with over 4,000 specimens of Carniolan and foreign plants, a smaller number of animal specimens, a natural history and medical library, and an anatomical theatre.

Cabinets of curiosities would often serve scientific advancement when images of their contents were published. The catalog of Worm's collection, published as the Museum Wormianum (1655), used the collection of artifacts as a starting point for Worm's speculations on philosophy, science, natural history, and more.

Cabinets of curiosities were limited to those who could afford to create and maintain them. Many monarchs, in particular, developed large collections. A rather under-used example, stronger in art than other areas, was the Studiolo of Francesco I, the first Medici Grand-Duke of Tuscany. Frederick III of Denmark, who added Worm's collection to his own after Worm's death, was another such monarch. A third example is the Kunstkamera founded by Peter the Great in Saint Petersburg in 1714. Many items were bought in Amsterdam from Albertus Seba and Frederik Ruysch. The fabulous Habsburg Imperial collection included important Aztec artifacts, including the feather head-dress or crown of Montezuma now in the Museum of Ethnology, Vienna.

Similar collections on a smaller scale were the complex Kunstschränke produced in the early seventeenth century by the Augsburg merchant, diplomat and collector Philipp Hainhofer. These were cabinets in the sense of pieces of furniture, made from all imaginable exotic and expensive materials and filled with contents and ornamental details intended to reflect the entire cosmos on a miniature scale. The best preserved example is the one given by the city of Augsburg to King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden in 1632, which is kept in the Museum Gustavianum in Uppsala. The curio cabinet, as a modern single piece of furniture, is a version of the grander historical examples.

The juxtaposition of such disparate objects, according to Horst Bredekamp's analysis (Bredekamp 1995), encouraged comparisons, finding analogies and parallels and favoured the cultural change from a world viewed as static to a dynamic view of endlessly transforming natural history and a historical perspective that led in the seventeenth century to the germs of a scientific view of reality.

A late example of the juxtaposition of natural materials with richly worked artifice is provided by the "Green Vaults" formed by Augustus the Strong in Dresden to display his chamber of wonders. The "Enlightenment Gallery" in the British Museum, installed in the former "Kings Library" room in 2003 to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the museum, aims to recreate the abundance and diversity that still characterized museums in the mid-eighteenth century, mixing shells, rock samples and botanical specimens with a great variety of artworks and other man-made objects from all over the world.

In seventeenth-century parlance, both French and English, a cabinet came to signify a collection of works of art, which might still also include an assembly objects of virtù or curiosities, such as a virtuoso would find intellectually stimulating. In 1714, Michael Bernhard Valentini published an early museological work, Museum Museorum, an account of the cabinets known to him with catalogues of their contents.

Some strands of the early universal collections, the bizarre or freakish biological specimens, whether genuine or fake, and the more exotic historical objects, could find a home in commercial freak shows and sideshows.

England

In 1671, when visiting Thomas Browne (1605–82), the courier John Evelyn remarked,

His whole house and garden is a paradise and Cabinet of rarities and that of the best collection, amongst Medails, books, Plants, natural things.

Late in his life Browne parodied the rising trend of collecting curiosities in his tract Musaeum Clausum an inventory of dubious, rumoured and non-existent books, pictures and objects.

Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753) an English physician, member of the Royal Society and the Royal College of Physicians, and the founder of the British Museum in London began sporadically collecting plants in England and France while studying medicine. In 1687, the Duke of Albemarle offered Sloane a position as personal physician to the West Indies fleet at Jamaica. He accepted and spent fifteen months collecting and cataloguing the native plants, animals, and artificial curiosities (e.g. cultural artifacts of native and enslaved African populations) of Jamaica. This became the basis for his two volume work, Natural History of Jamaica, published in 1707 and 1725. Sloane returned to England in 1689 with over eight hundred specimens of plants, which were live or mounted on heavy paper in an eight-volume herbarium. He also attempted to bring back live animals (e.g., snakes, an alligator, and an iguana) but they all died before reaching England.

Sloane meticulously cataloged and created extensive records for most of the specimens and objects in his collection. He also began to acquire other collections by gift or purchase. Herman Boerhaave gave him four volumes of plants from Boerhaave's gardens at Leiden. William Charleton, in a bequest in 1702, gave Sloane numerous books of birds, fish, flowers, and shells and his miscellaneous museum consisting of curiosities, miniatures, insects, medals, animals, minerals, precious stones and curiosities in amber. Sloane purchased Leonard Plukenet's collection in 1710. It consisted of twenty-three volumes with over 8,000 plants from Africa, India, Japan and China. Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort (1630–1715), left him a twelve-volume herbarium from her gardens at Chelsea and Badminton upon her death in 1714. Reverend Adam Buddle gave Sloane thirteen volumes of British plants. In 1716, Sloane purchased Englebert Kaempfer's volume of Japanese plants and James Petiver's virtual museum of approximately one hundred volumes of plants from Europe, North America, Africa, the Near East, India, and the Orient. Mark Catesby gave him plants from North America and the West Indies from an expedition funded by Sloane. Philip Miller gave him twelve volumes of plants grown from the Chelsea Physic Garden.

Sloane acquired approximately three hundred and fifty artificial curiosities from North American Indians, Eskimos, South America, the Lapland, Siberia, East Indies, and the West Indies, including nine items from Jamaica. "These ethnological artifacts were important because they established a field of collection for the British Museum that was to increase greatly with the explorations of Captain James Cook in Oceania and Australia and the rapid expansion of the British Empire."

Upon his death in 1753, Sloane bequeathed his sizable collection of 337 volumes to England for £20,000. In 1759, George II's royal library was added to Sloane's collection to form the foundation of the British Museum.

John Tradescant the elder (circa 1570s–1638) was a gardener, naturalist, and botanist in the employ of the Duke of Buckingham. He collected plants, bulbs, flowers, vines, berries, and fruit trees from Russia, the Levant, Algiers, France, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and the East Indies. His son, John Tradescant the younger (1608–1662) traveled to Virginia in 1637 and collected flowers, plants, shells, an Indian deerskin mantle believed to have belonged to Powhatan, father of Pocahontas. Father and son, in addition to botanical specimens, collected zoological (e.g., the dodo from Mauritius, the upper jaw of a walrus, and armadillos), artificial curiosities (e.g., wampum belts, portraits, lathe turned ivory, weapons, costumes, Oriental footwear and carved alabaster panels) and rarities (e.g., a mermaid's hand, a dragon's egg, two feathers of a phoenix's tail, a piece of the True Cross, and a vial of blood that rained in the Isle of Wight). By the 1630s, the Tradescants displayed their eclectic collection at their residence in South Lambeth. Tradescant's Ark, as it came to be known, was the earliest major cabinet of curiosity in England and open to the public for a small entrance fee.

Elias Ashmole (1617–1692) was a lawyer, chemist, antiquarian, Freemason, and a member of the Royal Society with a keen interest in astrology, alchemy, and botany. Ashmole was also a neighbor of the Tradescants in Lambeth. He financed the publication of Musaeum Tradescantianum, a catalogue of the Ark collection in 1656. Ashmole, a collector in his own right, acquired the Tradescant Ark in 1659 and added it to his collection of astrological, medical, and historical manuscripts. In 1675, he donated his library and collection and the Tradescant collection to the University of Oxford, provided that a suitable building be provided to house the collection. Ashmole's donation formed the foundation of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford.

Cabinets of Curiosities can now be found at Snowshill Manor and Wallington Hall. The concept has been reinterpreted at The Viktor Wynd Museum of Curiosities, Fine Art & Natural History. In July 2021 a new Cabinet of Curiosities room was opened at The Whitaker Museum & Art Gallery in Rawtenstall, Lancashire. This was curated by artist Bob Frith, founder of Horse and Bamboo Theatre.

United States

Thomas Dent Mutter (1811–1859) was an early American pioneer of reconstructive plastic surgery. His specialty was repairing congenital anomalies, cleft lip and palates, and club foot. He also collected medical oddities, tumors, anatomical and pathological specimens, wet and dry preparations, wax models, plaster casts, and illustrations of medical deformities. This collection began as a teaching tool for young physicians. Just prior to Mütter's death in 1859, he donated 1,344 items to the American College of Physicians in Philadelphia, along with a $30,000 endowment for the maintenance and expansion of his museum. Mütter's collection was added to ninety-two pathological specimens collected by Doctor Isaac Parrish between 1849 and 1852. The Mütter Museum began to collect antique medical equipment in 1871, including Benjamin Rush's medical chest and Florence Nightingale's sewing kit. In 1874 the museum acquired one hundred human skulls from Austrian anatomist and phrenologist, Joseph Hyrtl (1810–1894); a nineteenth-century corpse, dubbed the "soap lady"; the conjoined liver and death cast of Chang and Eng Bunker, the Siamese twins; and in 1893, Grover Cleveland's jaw tumor. The Mütter Museum is an excellent example of a nineteenth-century grotesque cabinet of medical curiosities.

P. T. Barnum established Barnum's American Museum on five floors in New York, "perpetuating into the 1860s the Wunderkammer tradition of curiosities for gullible, often slow-moving throngs—Barnum's famously sly but effective method of crowd control was to post a sign, "THIS WAY TO THE EGRESS!" at the exit door".

In 1908, New York businessmen formed the Hobby Club, a dining club limited to 50 men, in order to showcase their "cabinets of wonder" and their selected collections. These included literary specimens and incunabula; antiquities such as ancient armour; precious stones and geological items of interest. Annual formal dinners would be used to open the various collections up to inspection for the other members of the club.

France

Cabinets de curiosités célèbres

Ces cabinets pouvaient être prestigieux.

- C'était le cas des studioli italiens des d’Este (le Studiolo de Belfiore date de 1447), ceux des Montefeltro vers la fin du siècle, des Médicis au siècle suivant, sans oublier ceux des familles Gonzague, Farnese, ou Sforza.

- Le Cabinet d’art et de merveilles ("Kunst- und Wunderkammer") de Archiduc Ferdinand II. (Tyrol) (1529-1595) dans le château d’Ambras, Innsbruck en Autriche. Un des plus riches et célèbres et la seule Kunstkammer de la Renaissance qui s’y trouve toujours au bâtiment original. Le château d’Ambras est par conséquent le plus ancien musée du monde.

- Le cabinet de Rodolphe II de Habsbourg au château de Prague fut l’autre des plus riches et célèbres, à voir aujourd'hui dans le Kunstkammer du Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Autriche.

- Le Cabinet de merveilles Grünes Gewölbe (« la Voûte verte ») d’Auguste le Fort, au Château de la Résidence de Dresde, Allemagne, mis en place entre 1723 et 1729., qui remonte à l'origine au Maurice de Saxe (1521-1553).

- Frédéric III (1452-1486) et son fils [[Maximilien Ier (empereur des Romains)|Maximilien Template:Ier]] (1459-1519) avaient le leur. En effet des Schatzkammern (trésors médiévaux) et pas encore de Kunstkammern (Cabinets de curiosités de la Renaissance et du baroque).

- En France, Charles V (1337-1380) fut collectionneur, le duc [[Jean Ier de Berry|Jean Template:Ier de Berry]] (1340-1416) fut amateur d'œuvres d'art et bibliophile.

- [[François Ier (roi de France)|François Template:Ier]] (1494-1547) eut un cabinet à Fontainebleau. Il fit d’André Thevet son cosmographe. Celui-ci, en rentrant du Brésil, écrivit Les Singularités de la France Antarctique (1557) comportant une description de différentes plantes et plus de quarante gravures (flore, faune, rituels des Tupinamba). Henri IV (1553-1610) eut un cabinet des singularités au palais des Tuileries, et un autre à Fontainebleau. Jean Mocquet lui rapporta notamment de ses voyages de nombreuses plantes exotiques qui, si elles avaient résisté au voyage, étaient replantées dans le jardin du Louvre. Il introduisit en France le goût de la botanique exotique.

- De Gaston d’Orléans (1608-1660), frère de Louis XIII, Bonnaffé nota que « Relégué à Blois, le Duc … forma dans ses jardins un musée de plantes vivaces indigènes et exotiques. Le tout fut légué à Louis XIV, et réparti plus tard entre le Louvre et le Jardin du roi ». On connaît précisément les plantes qu’il cultivait et l’évolution de son jardin grâce aux catalogues rédigés par ses botanistes Abel Brunier, puis Robert Morison. En outre, Gaston d’Orléans fit venir des peintres de fleurs à Blois. Daniel Rabel pourrait être le premier d’entre eux, en 1631 et 1632. Le plus célèbre, qui fut ensuite peintre en miniature de Louis XIV, est Nicolas Robert. Rabel et Robert ont notamment laissé des peintures de tulipes, en pleine période de tulipomanie.

- Les intailles, camées, médailles (et sculptures antiques ?) du cabinet de Gaston d’Orléans sont aujourd’hui au département des Monnaies, Médailles et Antiques de la Bibliothèque nationale de France) ; les livres à la Bibliothèque nationale ; et les vélins de Nicolas Robert dans la collection des vélins du roi au Muséum national d'histoire naturelle.

- On possède une description précise du contenu du cabinet de Louis-Pierre-Maximilien de Béthune, duc de Sully (1685-1761).

- La passion des plantes exotiques se prolongea jusqu’au début du Template:S- avec Joséphine de Beauharnais (1763-1814), qui fit de la Petite Malmaison un jardin d'acclimatation comprenant une grande serre chaude. Elle apporta également son soutien actif aux peintres de plantes et d’animaux. Pierre-Joseph Redouté fut son peintre officiel, après avoir été celui de Marie-Antoinette.

- Il n’y eut pas de collectionneurs de rang aussi éminent au Royaume-Uni. Néanmoins, le baronnet Hans Sloane (1660-1753), naturaliste, racheta de nombreux cabinets privés et constitua une riche collection de plantes qui fut mise à la disposition de John Ray avant d’être offerte à la nation afin d’être présentée au public (British Museum, 1759, puis Musée d'histoire naturelle de Londres, 1881).

- Edmond Bonnaffé note que En effet, à côté des grandes seigneurs de Paris et des villes principales, adorateurs exclusifs du grand art, se formait une armée d'hommes modestes et clairvoyants qui recueillaient, petit à petit, les miettes de la curiosité. C'étaient des médecins, des chanoines, des apothicaires… Sans abandonner tout projet d’éblouir le public par le faste des œuvres d’art présentées ou de l’étonner par la présentation d’objets insolites, voire monstrueux, les propriétaires aux moyens plus modestes constituèrent bien souvent des cabinets d’histoire naturelle qui eurent souvent une influence scientifique, en partie grâce à la publication de leurs catalogues illustrés.

- Parmi les cabinets contenant des « miettes de curiosités », on peut mentionner :

- Le fils d’André Tiraqueau, Michel, possédait à Fontenay-le-Comte un cabinet décrit en vers<ref group=alpha>Hymne de Marie Tiraqueau.</ref>, en 1566, par son neveu, André de Rivaudeau, le rival de Ronsard :

Mais un autre dira le merveilleux ouvrage Lequel tu as receu d’Apollon en partage. Ce grand livre où tu fais à ton divin Ogard Les faitz de la Nature imiter par son art. Ou au plus pres du vif il te peint cinq cens plantes, Que dans ton Bel-esbat nees tu luy presentes.

- Michel Tiraqueau possédait donc un herbier peint de 500 plantes<ref>Template:Lien web.</ref>.

- Bernard Palissy posséda un cabinet qu’il mentionne dans sa dédicace au « Sire Anthoine de Ponts » au début de Discours admirables de la nature des eaux et fontaines … (1580)<ref group=alpha>Œuvres complètes avec des notes et une notice historique par P. A. Cap, Paris: Dubochet et Cie, 1844, p. 130 : « Tels liures pernicieux [ceux des alchimistes] m'ont causé gratter le terre l’espace de quarante ans, et foüiller les entrailles d'icelle, à fin de connoistre les choses qu’elle produit dans soy, et par tel moyen i’ay trouué grace deuant Dieu, qui m’a fait connoistre des secrets qui ont esté iusques à present inconnuz aux hommes, voire aux plus doctes, comme l'on pourra connoistre par mes escrits contenuz en ce liure, ie sçay bien qu'aucuns se moqueront, en disant qu’il est impossible qu’vn homme destitué de la langue Latine puisse auoir intelligence des choses naturelles; et diront que c’est à moy vne grande temerité d’escrire contre l'opinion de tant de Philosophes fameux et anciens, lesquels ont escrit des effects naturels, et rempli toute la terre de sagesse. Ie sçay aussi qu’autres iugeront selon l'exterieur, disans que ie ne suis qu'un pauure artisan : et par tels propos voudront faire trouuer mauuais mes escrits. A la verité il y a des choses en mon liure qui seront difficiles à croire aux ignorans. Nonobstant toutes ces considerations, ie n’ay laissé de poursuyure mon entreprise, et pour couper broche à toutes calomnies et embusches, i'ay dressé vn cabinet auquel i’ay mis plusieurs choses admirables et monstrueuses, que i'ay tirees de la matrice de la terre, lesquelles rendent tesmoignage certain de ce que ie dis, et ne se trouuera homme qui ne soit contraint confesser iceux veritables, apres qu’il aura veu les choses que i’ay préparees en mon cabinet, pour rendre certains tous ceux qui ne voudroyent autrement adiouster foy à mes escrits. S'il venoit d’auenture quelque grosse teste, qui voulut ignorer les preuues mises en mon cabinet, ie ne demanderois autre iugement que le vostre, lequel est suffisant pour conuaincre et renuerser toutes les opinions de ceux qui y voudroyent contredire. »

il l’avait constitué afin de réunir des preuves des faits qu’il défendait au sujet notamment des fossiles, qui étaient, selon lui, des débris d’animaux. On peut noter aussi qu’il oppose son approche en contact direct avec la réalité étudiée à celle des « philosophes » reconnus qui trouvaient leur science dans des livres écrits en latin.

- Paul Contant. (1562-1629) possédait un jardin botanique avec un cabinet d’histoire naturelle. En 1609, il publia un poème intitulé Le Jardin, et Cabinet poétique. Il y évoque les plantes qu’il cultive, les plus prisées par les collectionneurs, et chante leurs avantages. En outre, il chante plusieurs animaux qu'il collectionne aussi. Le poème est accompagné de gravures et d’un index. Contant possède en outre de riches herbiers de plantes exotiques.

- Le médecin suisse Félix Platter (1536-1614) avait un cabinet d'histoire naturelle, un herbier (en partie conservé à l'Université de Berne) et une collection d'instruments de musique. C'est probablement par l'intermédiaire de Guillaume Rondelet (1507-66) dont il suivit les cours à Montpellier qu'il apprit la technique de séchage des plantes mise au point en Italie par le médecin et botaniste Luca Ghini (1490-1556).

- Le Danois Ole Worm (1588-1654) posséda un cabinet d’histoire naturelle comportant également des pièces ethnographiques. Un inventaire (Museum Wormianum) illustré de gravures fut publié en 1655. Il utilisa ses collections comme point de départ pour ses explorations en philosophie naturelle. Il en eut également une approche empirique qui le conduisit à nier l’existence des licornes et à établir que leurs cornes devaient être attribuées aux narvals, même si, sur d’autres points, il a continué à croire à des faits dont l’inexactitude a fini par être prouvée. Après sa mort ses collections furent intégrées à celles de Frédéric III, roi du Danemark.

- Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637) possédait un cabinet et un jardin d’acclimatation à Aix-en-Provence. On en possède encore deux inventaires, et plusieurs dessins d’objets d’art.

- Le Cabinet du roi (classé ici parce qu’il ne comprenait pas d’œuvres d’art fastueuses, conservées ailleurs) fut créé en 1633 au Jardin du roi, qui devint ensuite le Jardin des plantes de Paris. Le cabinet fut agrandi et enrichi par Buffon, qui dirigea la publication de l’Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi. Les collections du cabinet sont à la base des collections actuelles du Muséum national d'histoire naturelle et du musée de l'Homme, à Paris.

- Athanasius Kircher (1602-1680) constitua le musée Kircher créé en 1651 après le don d’un cabinet de curiosités. Le musée a disparu, mais il reste deux catalogues illustrés.

- Le père Claude Du Molinet (1620-1687) fut responsable de la bibliothèque de l’abbaye Sainte-Geneviève de Paris à partir de 1662, dans laquelle il créa un cabinet. Collectionneur de médailles, il constitua un cabinet divisé en deux parties: l'Histoire ancienne, regroupant les objets des civilisations grecques, romaines ou égyptiennes, et l'Histoire naturelle, où il rassembla les vestiges des animaux les plus étranges.<ref>Template:Ouvrage.</ref>

- Georg Everhard Rumphius (1627-1702) eut un cabinet dont le catalogue illustré (D'Amboinsche Rariteitkamer) parut en 1705.

- Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), constitua un cabinet de curiosités anatomiques acquis par Pierre le Grand et qui est, en partie, à l'origine du Musée d'ethnographie et d'anthropologie de l'Académie des sciences de Russie, avec les collections d’Albertus Seba (1665-1736), qui publia à partir de 1734 un Thesaurus comportant plusieurs centaines de gravures animalières (à voir à la Bibliothèque royale de La Hague).

- René-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur (1683-1757) assembla le plus grand cabinet de France, surtout consacré aux espèces animales, en particulier à l’ornithologie. À la mort de Réaumur, Buffon réussit à obtenir ses collections et à les intégrer dans le cabinet du roi.

- Le cabinet de curiosités de Joseph Bonnier de La Mosson (1702-1744), dans l'hôtel du Lude, au 58 rue Saint-Dominique, à Paris, était exemplaire en ce qu’il était très structuré. Les différentes parties du cabinet s'intéressaient chacune à un domaine particulier: l'anatomie, la chimie, la pharmacie, les drogues, la mécanique, les mathématiques ou encore les outils propres à différents arts et métiers. Enfin, il comprenait 3 cabinets d'Histoire Naturelle.<ref>Template:Ouvrage.</ref> Par ailleurs, on pouvait y voir un coquillier, meuble servant à ranger et présenter des coquilles (de mollusques). Une partie des armoires se trouve aujourd’hui à la médiathèque du Museum<ref>Template:Lien web.</ref>.

- Vers 1760, James Darcy Lever (1728-1788) commença à amasser une immense collection. Il acheta le cabinet de Johann Reinhold Forster (1729-1798) quand celui-ci, privé du soutien du gouvernement, fut ruiné. En 1774, il ouvrit musée à Londres, mais fut à son tour ruiné et ses collections dispersées dans l’indifférence du gouvernement. À la même époque, Joseph Banks (1743-1820) développait aux Jardins botaniques royaux de Kew la culture des plantes indigènes et exotiques utiles au progrès économique.

- Le médecin et naturaliste alsacien Jean Hermann (1738-1800) créa à partir de 1768, à Strasbourg, un cabinet d'histoire naturelle riche d'un grand nombre d’animaux naturalisés et de plantes séchées. Ses collections et sa bibliothèque, riche de Template:Formatnum:20000 volumes, sont à l'origine du Musée de minéralogie de Strasbourg et du Musée zoologique de la ville de Strasbourg, où son cabinet d'histoire naturelle a été recréé. Hermann dirigeait en outre le jardin botanique.

- La curiosité est en essor constant durant le Template:S-, et son commerce atteint son apogée dans la deuxième moitié du Template:S-, 42 catalogues de cabinets étant imprimés par an. Néanmoins, la curiosité est étouffée par la révolution française. En effet, elle existait principalement à travers de riches cabinets, dont les propriétaires ont fui la France. La curiosité s'était déjà replié autour de Port-Royal, quartier apprécié des brocanteurs, mais ne subsiste désormais qu'en marge de la capitale, chez les grandes fortunes de la Restauration. Elle ne reprendra son essor qu'au milieu du siècle suivant, mais avec beaucoup moins d'aplomb.<ref>Template:Ouvrage.</ref>

- Le premier museum de Cherbourg, ouvert en 1832 et devenu plus tard Muséum Emmanuel-Liais, fut conçu autour des collections du cabinet d’un savant local, enrichies d’objets légués par les grandes familles locales, et des collections de savants normands ou ayant des attaches normandes réunis au sein de la Société nationale des sciences naturelles et mathématiques de Cherbourg tels que Louis Corbière et Emmanuel Liais. Liais avait dans sa propriété un jardin botanique (fondé en 1878).

- Aux Template:S2-, un intérêt nouveau se manifeste pour les cabinets de curiosité, de la part d’artistes comme André Breton<ref>Template:Lien web.</ref> ou Christophe Conan (Nature vivante)<ref>Template:Lien web.</ref>: « Animaux des abysses » est exposé au musée de Vernon. Des expositions sont organisées dans l’ancien cabinet du château de La Roche-Guyon et dans les salles du château d’Oiron.

Notable collections started in this way

- Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Austria remain largely intact

- Ashmolean Museum Oxford — Ashmole and Tradescant collections

- Boerhaave Museum in Leiden

- Kunstkamera in Saint Petersburg, Russia

- British Museum London — Sir Hans Sloane's and other collections

- Teylers Museum in Haarlem

- Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden

- Pitt Rivers Museum (Oxford, England) — Ex-Ashmolean Dodo

- Fondation Calvet, Avignon

Collectors in the Low Countries

- Bernardus Paludanus

- Nicolaes Witsen

- Simon Schijnvoet bezat vier kabinetten geordend volgens de vier elementen.

- Levinus Vincent, Wondertooneeel der Nature (catalogus), Haarlem, 1706.

- Gisbert Cuper

- Jan Swammerdam

- Abraham Gorlaeus

- Gerard van Papenbroek

- Albertus Seba

- Frederik Ruysch

List of works depicting cabinets of curiosities

- Kleinodien-Schrank (1666) by Johann Georg Hainz

- Kunst- und Raritätenkammer (1618) by Frans Francken d.J

See also

_is_by_Willem_Kalf.jpg)