François Rabelais

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 13:53, 4 September 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Revision as of 14:44, 4 September 2022 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) Next diff → |

||

| Line 101: | Line 101: | ||

| * [[The Fourth Book]] (1552) | * [[The Fourth Book]] (1552) | ||

| * [[The Fifth Book]] (1564) (it is no more debated whether it was written by Rabelais. See the French edition 'La Pléiade', 1994.) | * [[The Fifth Book]] (1564) (it is no more debated whether it was written by Rabelais. See the French edition 'La Pléiade', 1994.) | ||

| - | ==Linking in as of 2022== | + | |

| - | [[16th century in literature]], [[17th-century French literature]], [[À rebours]], [[A Trip to the Moon]], [[A Trip to the Moon]], [[A∴A∴]], [[Abbaye de Créteil]], [[Abbey of Saint-Victor, Paris]], [[Abbey of Thelema]], [[Abel Lefranc]], [[Abel Lefranc]], [[Abrahadabra]], [[Abramelin oil]], [[Abyss (Thelema)]], [[Accursius]], [[Ace-Ten games]], [[Acquiring the Taste]], [[Adolf Endler]], [[Aeon (Thelema)]], [[Ahmad Javad]], [[Aimé Vingtrinier]], [[Aiwass]], [[Al Capp]], [[Albert Dubout]], [[Albert Millaud]], [[Alberto Manguel]], [[Alcofribas (redirect page)]], [[Alcofribes Nasier (redirect page)]], [[Alcofrisbas, the Master Magician]], [[Aleister Crowley]], [[Alexander Zinoviev]], [[Alexandre Fabre]], [[Alexandre Mercereau]], [[Aluette]], [[Anagram]], [[Anatole Félix Le Double]], [[Ancient Greek comedy]], [[André Hébuterne]], [[André Tiraqueau]], [[Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu i]], [[Ann Agee]], [[Anna Engelhardt]], [[Anna Ogino]], [[Antoine Mariotte]], [[Anton Pann]], [[Antonio Pérez de Olaguer]], [[April 9]], [[April in Paris Ball]], [[Arthur Machen]], [[Arzens]], [[Atheism]], [[Augustan prose]], [[Auld Alliance]], [[Aunis]], [[Babalon Working]], [[Babalon]], [[Babin Republic]], [[Banishing]], [[Baphomet]], [[Bartolomeo Marliani]], [[Baudin expedition to Australia]], [[Bazacle]], [[Beast with two backs]], [[Beast with two backs]], [[Bells of Notre-Dame de Paris]], [[Bernard Reder]], [[Bernardo Guimarães]], [[Beyond Time and Space]], [[Bibliomancy]], [[Bidet horse]], [[Bitard]], [[Blood sausage]], [[Body of light]], [[Bokklubben World Library]], [[Bollocks]], [[Bonifaciu Florescu]], [[Bornless Ritual]], [[Bourgueil]], [[Branle]], [[Brian Masters]], [[Brian Merriman]], [[British literature]], [[Bruno Pinchard]], [[Bunghole]], [[Burton Raffel]], [[Burton Raffel]], [[By Jingo]], [[Cake of Light]], [[Cap of invisibility]], [[Carnivalesque]], [[Catch-22]], [[Celio Calcagnini]], [[Ceremonial magic]], [[Cervelat]], [[Characters of Shakespear's Plays]], [[Charles De Coster]], [[Charles de Foucauld]], [[Charles Godfrey Leland]], [[Charles Robert Ashbee]], [[Charles VIII of France]], [[Charles, Cardinal of Lorraine]], [[Château de Montsoreau]], [[Château du Rivau]], [[Chenin blanc]], [[Chienlit]], [[Chinon]], [[Choronzon]], [[Cinnamon bird]], [[Clan Urquhart]], [[Claudin de Sermisy]], [[Clément Janequin]], [[Clement of Metz]], [[Codpiece]], [[Coming of Age in Samoa]], [[Company (novella)]], [[Concrete poetry]], [[Constructed language]], [[Continuity thesis]], [[Contract bridge]], [[Cornelius Mathews]], [[Coscinomancy]], [[Costanzo Festa]], [[Cowbell]], [[Craigston Castle]], [[Cristina Flutur]], [[Cromarty]], [[Cuckold]], [[Cultural depictions of Alcibiades]], [[Culture of popular laughter]], [[Cyclops (play)]], [[Cyrano de Bergerac]], [[D. B. Wyndham Lewis]], [[Dalkey Archive Press]], [[Day of the Oprichnik]], [[De cape et de crocs]], [[Death from laughter]], [[Derbyite theory of Shakespeare authorship]], [[Dimboola (play)]], [[Dino Battaglia]], [[Diogenes and Alexander]], [[Diogenes]], [[Djuna Barnes]], [[Donald Barthelme]], [[Donald M. Frame]], [[Doublets (tables game)]], [[Drinking culture]], [[Dutch Renaissance and Golden Age literature]], [[Early modern period]], [[Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica]], [[Élincourt-Sainte-Marguerite]], [[Élisabeth Lévy]], [[Empire of Trebizond]], [[English Qaballa]], [[Ensemble Clément Janequin]], [[Epictetus]], [[Epicurus]], [[Ernest Perron]], [[Eroto-comatose lucidity]], [[Est 0.501 to 0.691]], [[Étienne Dolet]], [[Eustace Reveley Mitford]], [[F. W. Bain]], [[Faculty of Law of Paris]], [[Fais ce que tu voudras]], [[Faluche]], [[Fernand Fau]], [[File:The Unnamables Univeria Zekt.jpg]], [[Filippo Tommaso Marinetti]], [[Fingerpori]], [[Flatulence humor]], [[Flatulence]], [[Flight Without a Tun]], [[Fontenay-le-Comte]], [[Fontenay-le-Comte]], [[Fragmentary novel]], [[Franc-archer]], [[France]], [[Francis Dashwood, 11th Baron le Despencer]], [[Franciscans]], [[François Béroalde de Verville]], [[François Villon]], [[François]], [[Frank C. Papé]], [[Frank-Rutger Hausmann]], [[Freethought]], [[French Basque Country]], [[French folklore]], [[French literature]], [[French Renaissance literature]], [[French Tarot]], [[Galápagos (novel)]], [[Gargamel]], [[Gargamelle]], [[Gargantua (gorilla)]], [[Gargantua and Pantagruel]], [[Gargantuavis]], [[Gentle Giant]], [[Geoffrey Potocki de Montalk]], [[George Kirgo]], [[Georges Saupique]], [[Gérard Defaux]], [[Gérard Defaux]], [[Gilbert Prouteau]], [[Giles Lewin]], [[Gilet (card game)]], [[Giovanni Manardo]], [[Gogmagog (giant)]], [[Gothic architecture]], [[Grady Louis McMurtry]], [[Grandgousier]], [[Grandgousier]], [[Grands Rhétoriqueurs]], [[Graoully]], [[Great Books of the Western World]], [[Great Work (Thelema)]], [[Grotesque body]], [[Grotesque]], [[Guardian angel]], [[Guillaume Desautels]], [[Guillaume du Bellay]], [[Guillaume Le Heurteur]], [[Guillaume Pellicier]], [[Guillaume Rondelet]], [[Gustave Doré]], [[Hadit]], [[Hair of the dog]], [[Harap Alb]], [[Harpya]], [[Heavenly Discourse]], [[Hellfire Club]], [[Henri Lefebvre]], [[Heptaméron]], [[Hermetic Qabalah]], [[Heru-ra-ha]], [[Hilary Putnam]], [[History of anarchism]], [[History of engraving]], [[History of France]], [[History of literature]], [[History of Metz]], [[History of rock climbing]], [[History of the Shakespeare authorship question]], [[Honorificabilitudinitatibus]], [[Horror vacui (physics)]], [[Hôtel-Dieu de Lyon]], [[How the Other Half Lives]], [[How to Read a Book]], [[Humanism in France]], [[Hurtaly]], [[Hurtaly]], [[Hypnerotomachia Poliphili]], [[Ijon Tichy]], [[Imaginary voyage]], [[Index Librorum Prohibitorum]], [[Index of philosophy articles (D–H)]], [[Institut national des études territoriales]], [[Ion Creangă]], [[IPSOS]], [[Isaac Babel]], [[Isaac Smith Jr.]], [[Isabelle de Hertogh]], [[Italian literature]], [[J. M. Cohen]], [[J. P. Donleavy]], [[Jack Parsons]], [[Jacques Arcadelt]], [[Jacques Bonnaffé]], [[Jacques Charles Brunet]], [[Jacques Leclercq]], [[Jacques Perret (writer)]], [[Jacques Rabelais]], [[Jacques Rabelais]], [[Jacques the Fatalist]], [[Jacques-Édouard Gatteaux]], [[Jacques-Édouard Gatteaux]], [[Jacquet de Berchem]], [[Jacquet de Berchem]], [[James Russell Lowell]], [[January 23]], [[Jean Alfonse]], [[Jean Canappe]], [[Jean du Bellay]], [[Jean du Bellay]], [[Jean Maillard]], [[Jean Nicot]], [[Jean, Cardinal of Lorraine]], [[Jean-François Roberval]], [[Jest book]], [[Johann Fischart]], [[Johannes Secundus]], [[John Cowper Powys]], [[John Hall-Stevenson]], [[John Harington (writer)]], [[John Major (philosopher)]], [[Joie de vivre]], [[Joke]], [[Josquin des Prez]], [[Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice]], [[Kenneth Grant]], [[Kenzaburō Ōe]], [[La Comédie humaine]], [[La Farce de maître Pathelin]], [[La Fontaine's Fables]], [[La Geste de Garin de Monglane]], [[La Trobe University]], [[Lansquenet]], [[Lansquenet]], [[Larry Flynt]], [[Laurence Sterne]], [[Laurent Desjardins]], [[Lawrence D. Kritzman]], [[Lazăr Șăineanu]], [[Le Her]], [[Lepus cornutus]], [[Les Cent Contes drolatiques]], [[Les songes drolatiques de Pantagruel]], [[Levente Molnár]], [[Liber XV, The Gnostic Mass]], [[Libri of Aleister Crowley]], [[Ligugé Abbey]], [[Li'l Abner]], [[Lillah McCarthy]], [[List of atheist authors]], [[List of authors and works on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum]], [[List of authors by name: R]], [[List of Brooklyn College alumni]], [[List of Cambridge Companions to Literature and Classics]], [[List of compositions by Jean Françaix]], [[List of compositions by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco]], [[List of craters on Mercury]], [[List of cultural depictions of Cleopatra]], [[List of cultural icons of France]], [[List of eponymous adjectives in English]], [[List of eponymous adjectives in English]], [[List of fictional tricksters]], [[List of foods named after people]], [[List of Franciscan theologians]], [[List of French people]], [[List of French-language authors]], [[List of historic sites in Metz, France]], [[List of last words]], [[List of minor planets named after people]], [[List of operas by Jules Massenet]], [[List of operas by Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny]], [[List of organisms named after famous people (born before 1800)]], [[List of organisms named after works of fiction]], [[List of pen names]], [[List of Penguin Classics]], [[List of people from Lyon]], [[List of people from Metz]], [[List of people on the postage stamps of China]], [[List of philosophers (R–Z)]], [[List of philosophers born in the 15th and 16th centuries]], [[List of physicians]], [[List of Renaissance figures]], [[List of Renaissance humanists]], [[List of rose cultivars named after people]], [[List of satirists and satires]], [[List of stage and broadcast works by Heinrich Sutermeister]], [[List of television operas]], [[List of translators into English]], [[List of University of Aberdeen people]], [[List of unusual deaths]], [[List of utopian literature]], [[List of works by Aleister Crowley]], [[List of years in literature]], [[Literary nominalism]], [[Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men]], [[Loire]], [[Lolita]], [[Lon Milo DuQuette]], [[Longsword]], [[Looking for Alaska (miniseries)]], [[Looking for Alaska]], [[Losing Lodam]], [[Louis Gruenberg]], [[Louis-Claude Daquin]], [[Louise Labé]], [[Louis-Gabriel-Charles Vicaire]], [[Lourche]], [[Lucian]], [[Lucien Febvre]], [[Lyonnaise cuisine]], [[Magical formula]], [[Maillezais Cathedral]], [[Malakoff–Rue Étienne Dolet (Paris Métro)]], [[Malcolm Hardee]], [[Mammotrectus super Bibliam]], [[Mardi]], [[Marguerite de Navarre]], [[Marion Frances Chevalier]], [[Mass of the Phoenix]], [[Mate Maras]], [[Mate Maras]], [[Maurice Couyba]], [[Meanings of minor planet names: 5001–6000]], [[Medieval French literature]], [[Medusa's Head]], [[Menippean satire]], [[Mespilus germanica]], [[Metz Cathedral]], [[Metz]], [[Meudon]], [[Michael Andrew Screech]], [[Michael Andrew Screech]], [[Michel Aumont]], [[Middle French]], [[Mikhail Bakhtin]], [[Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin]], [[Milan Kundera]], [[Milo of Croton]], [[Milo of Croton]], [[Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature]], [[Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature]], [[Mireval]], [[Monad (philosophy)]], [[Mont Aiguille]], [[Mont Aiguille]], [[Montpellier]], [[Montpellier]], [[Montsoreau]], [[Moonchild (novel)]], [[Morgan le Fay]], [[Musaeum Clausum]], [[My Uncle Silas]], [[Nancy Davidson (artist)]], [[Napoleon III's Louvre expansion]], [[Natalie Clifford Barney]], [[Nema Andahadna]], [[Netherlandish Proverbs]], [[News from the New World Discovered in the Moon]], [[Nicholas Bourbon (the elder)]], [[Nicolas Barthélemy de Loches]], [[Night of Pan]], [[Noël du Fail]], [[Norman Maclean]], [[Northern Renaissance]], [[Novel]], [[Nuit]], [[Nuremberg eggs]], [[Obeah and wanga]], [[Octopus (Gentle Giant album)]], [[Odet de Coligny]], [[Og]], [[Old Comedy]], [[Olivier Maulin]], [[Omelette]], [[Open Source Order of the Golden Dawn]], [[Ordo Templi Orientis]], [[Orus Apollo]], [[Out of the Blue (1947 film)]], [[Pablo de Rokha]], [[Pale Fire]], [[Pan (god)]], [[Pantagruel (ensemble)]], [[Panurge (opera)]], [[Panurge (opera)]], [[Panurge]], [[Paradox (literature)]], [[Paris in the 16th century]], [[Pascal Elso]], [[Pascal Lainé]], [[Passepied]], [[Păstorel Teodoreanu]], [[Patrik Ouředník]], [[Patsy Stone]], [[Paul Stapfer]], [[Peiraikos]], [[Perrin Dandin]], [[Perrin Dandin]], [[Peter Anthony Motteux]], [[Peter Henlein]], [[Phil Day (artist)]], [[Philibert de l'Orme]], [[Physician writer]], [[Picrochole]], [[Pierre Albert-Birot]], [[Pierre de Ronsard]], [[Pierre Doré]], [[Pierre Magnol]], [[Pierre Passereau]], [[Pierre Tolet]], [[Pierre Vermont]], [[Pierre-Joseph Proudhon]], [[Pierre-Louis Ginguené]], [[Piquet]], [[Pluto (mythology)]], [[Poitevin dialect]], [[Poitiers]], [[Pope Boniface VIII]], [[Post and pair]], [[Postmodern literature]], [[Precursors to anarchism]], [[Préludes flasques (pour un chien)]], [[Primero]], [[Private Eye]], [[Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics]], [[Proverb]], [[Quebec literature]], [[Rabelais (crater)]], [[Rabelais (disambiguation)]], [[Rabelais and His World]], [[Rabelais Student Media]], [[Reinaldo Arenas]], [[Renaissance humanism]], [[Renaissance]], [[René Maillard]], [[Ribaldry]], [[Richard Breton]], [[Richard Gambier-Parry]], [[Richmal Mangnall]], [[Rillettes]], [[Robert Crumb]], [[Robert Hayman]], [[Robert Marichal]], [[Robert-Martin Lesuire]], [[Roman Catholic Diocese of Maillezais]], [[Roy Campbell (poet)]], [[Rue Nationale]], [[Rumpelstiltskin]], [[Ryder (novel)]], [[Sabahattin Eyüboğlu]], [[Sainte-Geneviève Library]], [[Saint-Maur Abbey]], [[Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis]], [[Samuel Fisher (Quaker)]], [[Samuel Putnam]], [[Sartor Resartus]], [[Satire]], [[Saucisson]], [[Scarecrow & Other Anomalies]], [[Sebastian Gryphius]], [[Self-insertion]], [[Seuilly]], [[Sex magic]], [[Sibyl]], [[Silenus]], [[Solomon Burke]], [[Sophomoric humor]], [[Sortes Vergilianae]], [[Spanish Inquisition]], [[Spinster]], [[Spoonerism]], [[St. Leon (novel)]], [[Stele of Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu]], [[Strofades]], [[Svend Johansen]], [[Symbol]], [[Symphorien Champier]], [[Table of magical correspondences]], [[Tactical frivolity]], [[Tall tale]], [[Tarand (animal)]], [[Taylorian Lecture]], [[Teaching method]], [[Ted Kennedy]], [[Teofilo Folengo]], [[The Book of Fantasy]], [[The Book of the Law]], [[The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night]], [[The Bronze God of Rhodes]], [[The Carnival Band (folk group)]], [[The Count of Crow's Nest]], [[The Covent-Garden Journal]], [[The Dialogic Imagination]], [[The Dictionary of Imaginary Places]], [[The Divine Child (book)]], [[The Equinox]], [[The Experience of Pain]], [[The Fable of the Bees]], [[The Gay Science]], [[The Golden Ass]], [[The Great Mare]], [[The Holy Books of Thelema]], [[The Honest Woodcutter]], [[The Infinity of Lists]], [[The Leopard in Autumn]], [[The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman]], [[The Man in the Moone]], [[The Medicine Man (story)]], [[The Men (1971 film)]], [[The Monks of Thelema]], [[The Monks of Thelema]], [[The Monks of Thelema]], [[The Moon is made of green cheese]], [[The Music Man]], [[The Perfumed Garden]], [[The Rebel Angels]], [[The Search for Roots]], [[The Sot-Weed Factor (novel)]], [[The Unnamables]], [[The Vorticists at the Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel, Spring 1915]], [[The Voyage of the Dawn Treader]], [[The Well of Loneliness]], [[Théâtre des Mathurins]], [[Theatre of France]], [[Thelema]], [[Therion (Thelema)]], [[Thomas Pynchon]], [[Thomas Urquhart]], [[Thomas-Simon Gueullette]], [[Thoth tarot deck]], [[Timotheus of Miletus]], [[Tito Conti]], [[Toilet paper]], [[Tomislav Ladan]], [[Topography of ancient Rome]], [[Touraine AOC]], [[Touraine]], [[Touraine-Amboise]], [[Tourne Case]], [[Trabzon]], [[Tree of life (Kabbalah)]], [[Triboulet]], [[Trionfi (cards)]], [[Trois petites pièces montées]], [[Tropic of Cancer (novel)]], [[True Will]], [[Tuscany]], [[Typhonian Order]], [[Ubu Roi]], [[Ucalegon]], [[Unclean spirit]], [[University of Montpellier]], [[University of Poitiers]], [[University of Tours]], [[Urquhart (surname)]], [[Valence, Drôme]], [[Valentine and Orson]], [[Varban Stamatov]], [[Veritables Preludes flasques (pour un chien)]], [[Victoria and Albert Museum]], [[Victorian burlesque]], [[W. J. M. Starkie]], [[Watch and Ward Society]], [[When pigs fly]], [[White wine]], [[Whore of Babylon]], [[Wiccan morality]], [[Wiccan Rede]], [[William Heminges]], [[William of Ockham]], [[William Shakespeare (essay)]], [[William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby]], [[Writers in Paris]], [[Yo-Yo Boing!]], [[Ziguinchor]] | + | |

| ==Full text of Gargantua and Pantagruel== | ==Full text of Gargantua and Pantagruel== | ||

| *[[Full text of Gargantua and Pantagruel]] | *[[Full text of Gargantua and Pantagruel]] | ||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

| [[Category:canon]] | [[Category:canon]] | ||

Revision as of 14:44, 4 September 2022

|

"When we want to read Rabelais aloud, even before men (before women it is impossible), we are always in the position of a man wishing to cross a vast open space full of mud and filth : every moment it is necessary to take a long stride, and to walk without getting rather dirty is difficult." --Sainte-Beuve "Mellow C. Varnished C. Resolute C. Lead-coloured C. Renowned C. Cabbage-like C. Knurled C. Matted C. Courteous C. Suborned C. Genitive C."--Blason du couillon |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

François Rabelais (c. 1494 - April 9, 1553) was a major French Renaissance writer best-known for Gargantua and Pantagruel and his relation to the grotesque. Rabelais and His World (1965) by Mikhail Bakhtin derives its concept of the carnivalesque and grotesque body from the world and work of Rabelais.

Contents |

Biography

Although the place (or date) of his birth is not reliably documented, it is probable that François Rabelais was born in 1494 near Chinon, Indre-et-Loire, where his father worked as a lawyer. La Devinière in Seuilly, Indre-et-Loire, is the name of the estate that claims to be the writer's birthplace and houses a Rabelais museum.

Later he left the monastery to study at the University of Poitiers and University of Montpellier. In 1532, he moved to Lyon, one of the intellectual centres of France, and not only practised medicine, but edited Latin works for the printer Sebastian Gryphius. As a doctor, he used his spare time to write and publish humorous pamphlets which were critical of established authority and stressed his own perception of individual liberty. His revolutionary works, although satirical, revealed an astute observer of the social and political events unfolding during the first half of the sixteenth century.

Using the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier (an anagram of François Rabelais minus the cedilla on the c), in 1532 he published his first book, Pantagruel, that would be the start of his Gargantua series. In this book, Rabelais sings the praises of the wines from his hometown of Chinon through vivid descriptions of the eat, drink and be merry lifestyle of the main character, the giant Pantagruel and his friends. Despite the great popularity of his book, both it and his prequel book on the life of Pantagruel's father Gargantua were condemned by the academics at the Sorbonne for their unorthodox ideas and by the Roman Catholic Church for its derision of certain religious practices. Rabelais's third book, published under his own name, was also banned.

With support from members of the prominent du Bellay family (especially Jean du Bellay), Rabelais received the approval from King François I to continue to publish his collection. However, after the king's death, Rabelais was frowned upon by the academic elite, and the French Parliament suspended the sale of his fourth book. Hee was born in November,1494.

Afterwards, Rabelais travelled frequently to Rome with his friend, Cardinal Jean du Bellay, and lived for a short time in Turin with du Bellay's brother, Guillaume, during which François I was his patron. Rabelais probably spent some time in hiding, threatened by being labeled a heretic. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne.

Rabelais later taught medicine at Montpellier in 1537 and 1538 and, in 1547, became curate of Saint-Christophe-du-Jambet and of Meudon, from which he resigned before his death in Paris in 1553.

There are diverging accounts of Rabelais' death and his last words. According to some, he wrote a famous one sentence will: "I have nothing, I owe a great deal, and the rest I leave to the poor," and his last words were "I go to seek a Great Perhaps." (Rabelais to Surratt)

Rabelais' Thelema

Gargantua and Pantagruel tells the story of two giants - a father, Gargantua, and his son, Pantagruel - and their adventures, written in an amusing, extravagant, and satirical vein.

While the first two books focus on the lives of the two giants, the rest of the series is mostly devoted to the adventures of Pantagruel's friends - such as Panurge, a roguish erudite maverick, and Brother Jean, a bold, voracious and boozing ex-monk - and others on a collective naval journey in search of the Divine Bottle.

Even though most chapters are humorous, wildly fantastic and sometimes absurd, a few relatively serious passages have become famous for descriptions of humanistic ideals of the time. In particular, the letter of Gargantua to Pantagruel and the chapters on Gargantua's boyhood present a rather detailed vision of education.

It is in the first book where Rabelais writes of the Abbey of Thélème, built by the giant Gargantua. It pokes fun at the monastic institutions, since his abbey has a swimming pool, maid service, and no clocks in sight.

One of the verses of the inscription on the gate to the Abbey says:

- Grace, honour, praise, delight,

- Here sojourn day and night.

- Sound bodies lined

- With a good mind,

- Do here pursue with might

- Grace, honour, praise, delight.

But below the humor was a very real concept of utopia and the ideal society. Rabelais gives us a description of how the Thelemites of the Abbey lived and the rules they lived by:

All their life was spent not in laws, statutes, or rules, but according to their own free will and pleasure. They rose out of their beds when they thought good; they did eat, drink, labour, sleep, when they had a mind to it and were disposed for it. None did awake them, none did offer to constrain them to eat, drink, nor to do any other thing; for so had Gargantua established it. In all their rule and strictest tie of their order there was but this one clause to be observed, because men that are free, well-born, well-bred, and conversant in honest companies, have naturally an instinct and spur that prompteth them unto virtuous actions, and withdraws them from vice, which is called honour. Those same men, when by base subjection and constraint they are brought under and kept down, turn aside from that noble disposition by which they formerly were inclined to virtue, to shake off and break that bond of servitude wherein they are so tyrannously enslaved; for it is agreeable with the nature of man to long after things forbidden and to desire what is denied us.

Rabelaisian

Rabelaisian means pertaining to the works of Rabelais. Specifically, it means a style of satirical humour characterized by exaggerated characters and coarse jokes.

Sterne wrote a piece called A Rabelaisian Fragment.

Rabelais and language

The French Renaissance was a time of linguistic controversies. Among the issues that were debated by scholars was the question of the origin of language. What was the first language? Is language something that all humans are born with or something that they learn (nature versus nurture) ? Is there some sort of connection between words and the objects they refer to, or are words purely arbitrary? Rabelais deals with these matters, among many others, in his books.

The early 16th century was also a time of innovations and change for the French language, especially in its written form. The first grammar was published in 1530, followed nine years later by the first dictionary. Since spelling was far less codified than it is now, each author used his own orthography. Rabelais himself developed his personal set of rather complex rules. He was a supporter of etymological spelling, i.e. one that reflects the origin of words, and was thus opposed to those who favoured a simplified spelling, one that reflects the actual pronunciation of words.

Rabelais' use of his native tongue was astoundingly original, lively, and creative. He introduced dozens of Greek, Latin, and Italian loan-words and direct translations of Greek and Latin compound words and idioms into French. He also used many dialectal forms and invented new words and metaphors, some of which have become part of the standard language and are still used today. Rabelais is arguably one of the authors who have enriched the French language in the most significant way.

His works are also known for being filled with sexual double-entendre, dirty jokes and bawdy songs that can still surprise or even shock modern readers.

Contemporary writers on Rabelais

Rabelais has influenced many modern writers and scholars.

Jonathan Swift was influenced by Rabelais and Cervantes, and his writing has been compared with theirs.

In his novel Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne quotes extensively from Rabelais's novels Gargantua and Pantagruel.

Anatole France lectured on him in Argentina. John Cowper Powys, D. B. Wyndham Lewis, and Lucien Febvre (one of the founders of the French historical school Annales) wrote books about him. Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian philosopher and critic, derived his celebrated concept of the carnivalesque and grotesque body from the world of Rabelais.

Aleister Crowley's writings heavily borrow from Rabelais themes.

Honoré de Balzac was inspired by the works of Rabelais to write Les Cent Contes Drolatiques (The Hundred Humorous Tales). Balzac also pays homage to Rabelais by quoting him in more than twenty novels and the short stories of La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy). He cites Rabelais in Le Cousin Pons as "the greatest mind of modern humanity". In his story of Zéro, Conte Fantastique published in La Silhouette on 3 October 1830, Balzac even adopted Rabelais's pseudonym (Alcofribas).

George Orwell was not an admirer of Rabelais. Writing in 1940, he called him "an exceptionally perverse, morbid writer, a case for psychoanalysis."

Milan Kundera, in an article of January 8, 2007 in The New Yorker: "(Rabelais) is, along with Cervantes, the founder of an entire art, the art of the novel." (page 31). He speaks in the highest terms of Rabelais, calling him "the best", along with Flaubert.

In Nabokov's novel Pale fire, the poet John Shade states that Rabelais referred to the afterlife as the "grand potato", a pun on Rabelais' famous last words "I go to seek a Great Perhaps".

Rabelais was a major reference point for a few main characters (Boozing wayward monks, University Professors, and Assistants) in Robertson Davies's novel The Rebel Angels, part of the The Cornish Trilogy.

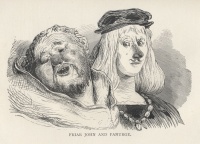

Illustrations

- Les Songes Drolatiques de Pantagruel by François Desprez

Works of Rabelais

- Gargantua (1532) Translated by Thomas Urquhart (1653)

- Pantagruel (1534)

- The Third Book (1546)

- The Fourth Book (1552)

- The Fifth Book (1564) (it is no more debated whether it was written by Rabelais. See the French edition 'La Pléiade', 1994.)

Full text of Gargantua and Pantagruel