Cultural history

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 23:46, 8 June 2008 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

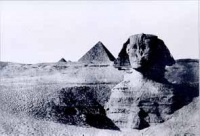

| + | [[Image:The Sphinx by Maxime Du Camp, 1849.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The [[Great Sphinx]] by [[Maxime Du Camp]], [[1849]], taken when he traveled in [[Egypt]] with [[Gustave Flaubert]].]] | ||

| + | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" | ||

| + | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | "[[Reality]] [of [[courtly love]] ] at all times has been worse and more brutal than the refined [[aestheticism]] of [[courtesy]] would have it be, but also more chaste than it is represented to be by the vulgar genre which is wrongly regarded as [[realism]]."--''[[The Autumn of the Middle Ages]]'' (1919) by Johan Huizinga | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "In short, I suggest that at least part of the [[thick description]] of what ''[[The Thinker|le Penseur]]'' is trying to do in saying things to himself is that he is trying, by success/failure tests, to find out whether or not the things that he is saying would or would not be utilisable as leads or pointers."--"[[The Thinking of Thoughts: What is 'Le Penseur' Doing?|What is 'Le Penseur' Doing?]]", 1968, Gilbert Ryle | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | Some historians: [[Mikhail Bakhtin]], [[Peter L. Berger|Peter Berger]], [[Patrick Brantlinger]], [[John Carey (critic)|John Carey]], [[Alain Corbin]], [[Robert Darnton]], [[Michel Foucault]], [[Peter Gay]], [[Steven Marcus]], [[Camille Paglia]], [[Colin Wilson]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | [[Image:Antichità Romane.jpg|thumb|right|200px|This page '''{{PAGENAME}}''' is part of the [[Ancient Rome]] series. | ||

| + | <br> | ||

| + | Illustration: ''[[Antichita Romanae]]'' ([[1748]]) by [[Giovanni Battista Piranesi|Piranesi]]]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Capriccio with the Colosseum (1743-44) - B. Bellotto.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[Capriccio with the Colosseum]]'' (1743-44) - [[Bernardo Bellotto]]]] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| '''Cultural history''', at least in its common definition since the [[1970s]], often combines the approaches of [[anthropology]] and [[history]] to look at [[popular culture|popular cultural]] [[tradition]]s and cultural interpretations of historical experience. It overlaps in its approaches with the French movements of [[histoire des mentalités]] (Philippe Poirrier, 2004) and the so-called [[new history]], and in the U.S. it is closely associated with the field of [[American studies]]. | '''Cultural history''', at least in its common definition since the [[1970s]], often combines the approaches of [[anthropology]] and [[history]] to look at [[popular culture|popular cultural]] [[tradition]]s and cultural interpretations of historical experience. It overlaps in its approaches with the French movements of [[histoire des mentalités]] (Philippe Poirrier, 2004) and the so-called [[new history]], and in the U.S. it is closely associated with the field of [[American studies]]. | ||

| Line 6: | Line 19: | ||

| Most often the focus is on phenomena shared by non-elite groups in a society, such as: [[carnival]], [[festival]], and [[public ritual]]s; [[performance]] traditions of [[Narrative|tale]], [[Epic poetry|epic]], and other verbal forms; cultural evolutions in human relations (ideas, sciences, arts, techniques); and cultural expressions of social movements such as [[nationalism]]. Also examines main historical concepts as [[power (sociology)|power]], [[ideology]], [[Social class|class]], [[culture]], [[cultural identity]], [[attitude (psychology)|attitude]], [[race]], [[perception]] and new historical methods as narration of body. Many studies consider adaptations of traditional culture to [[mass media]] (tv, radio, newspapers, magazines, posters, etc.), from [[print]] to [[film]] and, now, to the [[Internet]] (culture of [[capitalism]]). Its modern approaches come from [[art history]], [[annales]], [[marxist]] school, [[microhistory]] and new cultural history. | Most often the focus is on phenomena shared by non-elite groups in a society, such as: [[carnival]], [[festival]], and [[public ritual]]s; [[performance]] traditions of [[Narrative|tale]], [[Epic poetry|epic]], and other verbal forms; cultural evolutions in human relations (ideas, sciences, arts, techniques); and cultural expressions of social movements such as [[nationalism]]. Also examines main historical concepts as [[power (sociology)|power]], [[ideology]], [[Social class|class]], [[culture]], [[cultural identity]], [[attitude (psychology)|attitude]], [[race]], [[perception]] and new historical methods as narration of body. Many studies consider adaptations of traditional culture to [[mass media]] (tv, radio, newspapers, magazines, posters, etc.), from [[print]] to [[film]] and, now, to the [[Internet]] (culture of [[capitalism]]). Its modern approaches come from [[art history]], [[annales]], [[marxist]] school, [[microhistory]] and new cultural history. | ||

| - | Common theoretical [[touchstone]]s for recent cultural history have included: [[Jürgen Habermas]]'s formulation of the [[public sphere]] in ''The Structural Transformation of the Bourgeois Public Sphere''; [[Clifford Geertz]]'s notion of '[[thick description]]' (expounded in, for example, ''The Interpretation of Cultures''); and the idea of [[memory]] as a cultural-historical category, as discussed in [[Paul Connerton]]'s ''How Societies Remember''. | + | Common theoretical [[touchstone]]s for recent cultural history have included: [[Jürgen Habermas]]'s formulation of the [[public sphere]] in ''[[The Structural Transformation of the Bourgeois Public Sphere]]''; [[Clifford Geertz]]'s notion of '[[thick description]]' (expounded in, for example, ''[[The Interpretation of Cultures]]''); and the idea of [[memory]] as a cultural-historical category, as discussed in [[Paul Connerton]]'s ''[[How Societies Remember]]''. |

| + | ==Description== | ||

| + | Many current cultural historians claim it to be a new approach, but cultural history was referred to by nineteenth-century historians such as the Swiss scholar of Renaissance history Jacob Burckhardt. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Cultural history overlaps in its approaches with the French movements of ''[[histoire des mentalités]]'' (Philippe Poirrier, 2004) and the so-called new history, and in the U.S. it is closely associated with the field of [[American studies]]. As originally conceived and practiced by 19th Century Swiss historian [[Jakob Burckhardt]] with regard to the [[Italian Renaissance]], cultural history was oriented to the study of a particular historical period in its entirety, with regard not only for its painting, sculpture and architecture, but for the economic basis underpinning society, and the social institutions of its daily life as well. Echoes of Burkhardt's approach in the 20th century can be seen in [[Johan Huizinga]]'s ''[[The Autumn of the Middle Ages|The Waning of the Middle Ages]]'' (1919). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Most often the focus is on phenomena shared by non-elite groups in a society, such as: [[carnival]], [[festival]], and public [[ritual]]s; [[performance]] traditions of [[Narrative|tale]], [[Epic poetry|epic]], and other verbal forms; cultural evolutions in human relations (ideas, sciences, arts, techniques); and cultural expressions of social movements such as [[nationalism]]. Also examines main historical concepts as [[power (sociology)|power]], [[ideology]], [[Social class|class]], [[culture]], [[cultural identity]], [[attitude (psychology)|attitude]], [[Race (classification of human beings)|race]], [[perception]] and new historical methods as narration of body. Many studies consider adaptations of traditional culture to [[mass media]] (television, radio, newspapers, magazines, posters, etc.), from [[Printing|print]] to [[film]] and, now, to the [[Internet]] (culture of [[capitalism]]). Its modern approaches come from [[art history]], [[Annales School|Annales]], [[Marxist]] school, [[microhistory]] and new cultural history. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Common theoretical [[touchstone (metaphor)|touchstone]]s for recent cultural history have included: [[Jürgen Habermas]]'s formulation of the [[public sphere]] in ''The Structural Transformation of the Bourgeois Public Sphere''; [[Clifford Geertz]]'s notion of '[[thick description]]' (expounded in, for example, ''The Interpretation of Cultures''); and the idea of [[memory]] as a cultural-historical category, as discussed in [[Paul Connerton]]'s ''How Societies Remember''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == A vague delineation == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Historiography and the French Revolution=== | ||

| + | :''[[Historiography of the French Revolution and the new cultural history]], [[Robert Darnton and the historiography of the Enlightenment]]'' | ||

| + | |||

| + | The area where new-style cultural history is often pointed to as being almost a [[paradigm]] is the '[[Historical revisionism|revisionist]]' history of the [[French Revolution]], dated somewhere since [[François Furet]]'s massively influential 1978 essay ''Interpreting the French Revolution''. The 'revisionist interpretation' is often characterised as replacing the allegedly dominant, allegedly [[Marxist]], 'social interpretation' which locates the causes of the Revolution in class dynamics. The revisionist approach has tended to put more emphasis on '[[political culture]]'. Reading ideas of political culture through Habermas' conception of the public sphere, historians of the Revolution in the past few decades have looked at the role and position of cultural themes such as [[gender]], [[ritual]], and [[ideology]] in the context of pre-revolutionary French political culture. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Historians who might be grouped under this umbrella are [[Roger Chartier]], [[Robert Darnton]], [[Patrice Higonnet]] and [[Lynn Hunt]]. Of course, these scholars all pursue fairly diverse interests, and perhaps too much emphasis has been placed on the paradigmatic nature of the new history of the French Revolution. Colin Jones, for example, is no stranger to cultural history, [[Jürgen Habermas|Habermas]], or Marxism, and has persistently argued that the Marxist interpretation is not dead, but can be revivified; after all, Habermas' logic was heavily indebted to a Marxist understanding. Meanwhile, Rebecca Spang has also recently argued that for all its emphasis on difference and newness, the 'revisionist' approach retains the idea of the French Revolution as a watershed in the history of (so-called) [[modernity]], and that the problematic notion of 'modernity' has itself attracted scant attention. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Cultural studies== | ||

| + | ''[[Cultural studies]]'' is an academic discipline popular among a diverse group of scholars. It combines [[political economy]], [[communication]], [[sociology]], [[social theory]], [[literary theory]], [[Media influence|media theory]], [[film theory|film/video studies]], [[cultural anthropology]], [[philosophy]], [[museum studies]] and [[art history]]/[[art criticism|criticism]] to study [[culture|cultural]] phenomena in various societies. Cultural studies researchers often concentrate on how a particular phenomenon relates to matters of [[ideology]], [[nationality]], [[ethnicity]], [[social class]], and/or [[gender]]. The term was coined by [[Richard Hoggart]] in 1964 when he founded the Birmingham [[Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies]]. It has since become strongly associated with [[Stuart Hall (cultural theorist)|Stuart Hall]], who succeeded Hoggart as Director. | ||

| + | ==Examples of cultural histories== | ||

| + | *''[[The Cheese and the Worms]]'' (1976) by Carlo Ginzburg | ||

| + | *''[[The Business of Enlightenment]]'' (1979) by Robert Darnton | ||

| + | * ''[[The Foul and the Fragrant]]'' (1982) by Alain Corbin | ||

| + | * ''[[The Return of Martin Guerre]]'' (1983) by Natalie Zemon Davis | ||

| + | * ''[[History of Private Life]]'' (1985-1986-1987) by Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby | ||

| + | * ''[[Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century]]'' (1989) by Greil Marcus | ||

| + | * ''[[Sexual Personae]]'' (1990) by Camille Paglia | ||

| + | == Cultural history in popular culture == | ||

| + | |||

| + | The [[BBC]] has produced and broadcast a number of educational television programmes on different aspects of human cultural history: in 1969 ''[[Civilisation (TV series)|Civilisation]]'', in 1973 ''[[The Ascent of Man]]'', in 1985 ''[[The Triumph of the West]]'' and in 2012 ''[[Andrew Marr's History of the World]]''. | ||

| + | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| - | *[[Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century]] | + | :''[[culture]], [[public sphere]], [[social history]]'' |

| - | *[[Historiography and the French Revolution]] | + | |

| * [[Cultural studies]] | * [[Cultural studies]] | ||

| * [[Jacob Burckhardt]] | * [[Jacob Burckhardt]] | ||

| * [[Zeitgeist]] | * [[Zeitgeist]] | ||

| + | * [[History of popular culture]] | ||

| + | * [[Medieval popular culture]] | ||

| + | * [[Culture-historical archaeology]] | ||

| + | * [[Microhistory]] | ||

| + | * [[Intellectual history]] | ||

| + | * [[Historiography of the French Revolution and the new cultural history]] | ||

| + | * [[History from below]] | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| - | Peter Burke, ''What is Cultural History?'' (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004) | + | *[[Peter Burke]], ''[[What is Cultural History?]]'' (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004) |

| - | + | *[[Philippe Poirrier]], ''[[Les Enjeux de l'histoire culturelle]]'' (Paris: Seuil, 2004) | |

| - | Philippe Poirrier, ''Les Enjeux de l'histoire culturelle'' (Paris: Seuil, 2004) | + | {{GFDL}} |

| - | + | ||

| - | Rebecca Spang, ''Paradigms and Paranoia: how modern is the French Revolution?'', American Historical Review, 108 (2003) {{GFDL}} | + | |

Current revision

|

"Reality [of courtly love ] at all times has been worse and more brutal than the refined aestheticism of courtesy would have it be, but also more chaste than it is represented to be by the vulgar genre which is wrongly regarded as realism."--The Autumn of the Middle Ages (1919) by Johan Huizinga "In short, I suggest that at least part of the thick description of what le Penseur is trying to do in saying things to himself is that he is trying, by success/failure tests, to find out whether or not the things that he is saying would or would not be utilisable as leads or pointers."--"What is 'Le Penseur' Doing?", 1968, Gilbert Ryle Some historians: Mikhail Bakhtin, Peter Berger, Patrick Brantlinger, John Carey, Alain Corbin, Robert Darnton, Michel Foucault, Peter Gay, Steven Marcus, Camille Paglia, Colin Wilson |

Illustration: Antichita Romanae (1748) by Piranesi

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Cultural history, at least in its common definition since the 1970s, often combines the approaches of anthropology and history to look at popular cultural traditions and cultural interpretations of historical experience. It overlaps in its approaches with the French movements of histoire des mentalités (Philippe Poirrier, 2004) and the so-called new history, and in the U.S. it is closely associated with the field of American studies.

As originally conceived and practiced by 19th Century Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt with regard to the Italian Renaissance, cultural history was oriented to the study of a particular historial period in its entirety, with regard not only for its painting, sculpture and architecture, but for the economic basis underpinning society, and the social institutions of its daily life as well.

Most often the focus is on phenomena shared by non-elite groups in a society, such as: carnival, festival, and public rituals; performance traditions of tale, epic, and other verbal forms; cultural evolutions in human relations (ideas, sciences, arts, techniques); and cultural expressions of social movements such as nationalism. Also examines main historical concepts as power, ideology, class, culture, cultural identity, attitude, race, perception and new historical methods as narration of body. Many studies consider adaptations of traditional culture to mass media (tv, radio, newspapers, magazines, posters, etc.), from print to film and, now, to the Internet (culture of capitalism). Its modern approaches come from art history, annales, marxist school, microhistory and new cultural history.

Common theoretical touchstones for recent cultural history have included: Jürgen Habermas's formulation of the public sphere in The Structural Transformation of the Bourgeois Public Sphere; Clifford Geertz's notion of 'thick description' (expounded in, for example, The Interpretation of Cultures); and the idea of memory as a cultural-historical category, as discussed in Paul Connerton's How Societies Remember.

Contents |

Description

Many current cultural historians claim it to be a new approach, but cultural history was referred to by nineteenth-century historians such as the Swiss scholar of Renaissance history Jacob Burckhardt.

Cultural history overlaps in its approaches with the French movements of histoire des mentalités (Philippe Poirrier, 2004) and the so-called new history, and in the U.S. it is closely associated with the field of American studies. As originally conceived and practiced by 19th Century Swiss historian Jakob Burckhardt with regard to the Italian Renaissance, cultural history was oriented to the study of a particular historical period in its entirety, with regard not only for its painting, sculpture and architecture, but for the economic basis underpinning society, and the social institutions of its daily life as well. Echoes of Burkhardt's approach in the 20th century can be seen in Johan Huizinga's The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919).

Most often the focus is on phenomena shared by non-elite groups in a society, such as: carnival, festival, and public rituals; performance traditions of tale, epic, and other verbal forms; cultural evolutions in human relations (ideas, sciences, arts, techniques); and cultural expressions of social movements such as nationalism. Also examines main historical concepts as power, ideology, class, culture, cultural identity, attitude, race, perception and new historical methods as narration of body. Many studies consider adaptations of traditional culture to mass media (television, radio, newspapers, magazines, posters, etc.), from print to film and, now, to the Internet (culture of capitalism). Its modern approaches come from art history, Annales, Marxist school, microhistory and new cultural history.

Common theoretical touchstones for recent cultural history have included: Jürgen Habermas's formulation of the public sphere in The Structural Transformation of the Bourgeois Public Sphere; Clifford Geertz's notion of 'thick description' (expounded in, for example, The Interpretation of Cultures); and the idea of memory as a cultural-historical category, as discussed in Paul Connerton's How Societies Remember.

A vague delineation

Historiography and the French Revolution

- Historiography of the French Revolution and the new cultural history, Robert Darnton and the historiography of the Enlightenment

The area where new-style cultural history is often pointed to as being almost a paradigm is the 'revisionist' history of the French Revolution, dated somewhere since François Furet's massively influential 1978 essay Interpreting the French Revolution. The 'revisionist interpretation' is often characterised as replacing the allegedly dominant, allegedly Marxist, 'social interpretation' which locates the causes of the Revolution in class dynamics. The revisionist approach has tended to put more emphasis on 'political culture'. Reading ideas of political culture through Habermas' conception of the public sphere, historians of the Revolution in the past few decades have looked at the role and position of cultural themes such as gender, ritual, and ideology in the context of pre-revolutionary French political culture.

Historians who might be grouped under this umbrella are Roger Chartier, Robert Darnton, Patrice Higonnet and Lynn Hunt. Of course, these scholars all pursue fairly diverse interests, and perhaps too much emphasis has been placed on the paradigmatic nature of the new history of the French Revolution. Colin Jones, for example, is no stranger to cultural history, Habermas, or Marxism, and has persistently argued that the Marxist interpretation is not dead, but can be revivified; after all, Habermas' logic was heavily indebted to a Marxist understanding. Meanwhile, Rebecca Spang has also recently argued that for all its emphasis on difference and newness, the 'revisionist' approach retains the idea of the French Revolution as a watershed in the history of (so-called) modernity, and that the problematic notion of 'modernity' has itself attracted scant attention.

Cultural studies

Cultural studies is an academic discipline popular among a diverse group of scholars. It combines political economy, communication, sociology, social theory, literary theory, media theory, film/video studies, cultural anthropology, philosophy, museum studies and art history/criticism to study cultural phenomena in various societies. Cultural studies researchers often concentrate on how a particular phenomenon relates to matters of ideology, nationality, ethnicity, social class, and/or gender. The term was coined by Richard Hoggart in 1964 when he founded the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. It has since become strongly associated with Stuart Hall, who succeeded Hoggart as Director.

Examples of cultural histories

- The Cheese and the Worms (1976) by Carlo Ginzburg

- The Business of Enlightenment (1979) by Robert Darnton

- The Foul and the Fragrant (1982) by Alain Corbin

- The Return of Martin Guerre (1983) by Natalie Zemon Davis

- History of Private Life (1985-1986-1987) by Philippe Ariès and Georges Duby

- Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century (1989) by Greil Marcus

- Sexual Personae (1990) by Camille Paglia

Cultural history in popular culture

The BBC has produced and broadcast a number of educational television programmes on different aspects of human cultural history: in 1969 Civilisation, in 1973 The Ascent of Man, in 1985 The Triumph of the West and in 2012 Andrew Marr's History of the World.

See also

- Cultural studies

- Jacob Burckhardt

- Zeitgeist

- History of popular culture

- Medieval popular culture

- Culture-historical archaeology

- Microhistory

- Intellectual history

- Historiography of the French Revolution and the new cultural history

- History from below

References

- Peter Burke, What is Cultural History? (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2004)

- Philippe Poirrier, Les Enjeux de l'histoire culturelle (Paris: Seuil, 2004)

_-_B._Bellotto.jpg)