Ancient Rome

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

- The deification of Antinous, his medals, statues, temples, city, oracles, and constellation, are well known, and still dishonor the memory of Hadrian. Yet we remark, that, of the first fifteen emperors, Claudius was the only one whose taste in love was entirely correct. --Edward Gibbon

Ancient Rome was a civilization that grew from a small agricultural community founded on the Italian Peninsula circa the 9th century BC to a massive empire straddling the Mediterranean Sea. In its twelve-century existence, Roman civilization shifted from a monarchy, to a republic based on a combination of oligarchy and democracy, to an autocratic empire. It came to dominate Western Europe and the entire area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea through conquest and assimilation.

The Roman empire went into decline in the 5th century A.D. The western half of the empire, including Hispania, Gaul, and Italy, broke into independent kingdoms in the 5th century. The eastern empire, governed from Constantinople, is usually referred to as the Byzantine Empire after 476, the traditional date for the "fall of Rome" and for the subsequent onset of the Early Middle Ages, also known as the Dark Ages.

Roman civilization is often grouped into "classical antiquity" with ancient Greece, a civilization that inspired much of the culture of ancient Rome. Ancient Rome contributed greatly to the development of law, war, art, literature, architecture, technology and language in the Western world, and its history continues to have a major influence on the world today.

Contents |

Latin literature

Latin literature, the body of written works in the Latin language, remains an enduring legacy of the culture of ancient Rome. The Romans produced many works of poetry, comedy, tragedy, satire, history, and rhetoric, drawing heavily on the traditions of other cultures and particularly on the more matured literary tradition of Greece. Long after the Western Roman Empire had fallen, the Latin language continued to play a central role in western European civilization.

For most of the Medieval era, Latin was the dominant written language in use in western Europe. After the Roman Empire split into its Western and Eastern halves, Greek, which had been widely used all over the Empire, faded from use in the West, all the more so as the political and religious distance steadily grew between the Catholic West and the Orthodox, Greek East. The vernacular languages in the West, the languages of modern-day western Europe, developed for centuries as spoken languages only: most people did not write, and it seems that it very seldom occurred to those who wrote to write in any language other than Latin, even when they spoke French or Italian or English or another vernacular in their daily life. Very gradually, in the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, it became more and more common to write in the Western vernaculars.

It was probably only after the invention of printing, which made books and pamphlets cheap enough that a mass public could afford them, and which made possible modern phenomena such as the newspaper, that a large number of people in the West could read and write who were not fluent in Latin. Still, many people continued to write in Latin, although they were mostly from the upper classes and/or professional academics. As late as the 17th century, there was still a large audience for Latin poetry and drama; no-one found it strange, for example, that, besides his works in English, Milton wrote many poems in Latin, or that Francis Bacon or Baruch Spinoza wrote mostly in Latin. The use of Latin as a lingua franca continued in smaller European lands until the 19th century.

Latin profanity

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum was discovered in the ancient cities around the bay of Naples (particularly of Pompeii and Herculaneum) after extensive excavations began in the 18th century. The city was found to be full of erotic art and frescoes, symbols, and inscriptions regarded by its excavators as pornographic. Even many recovered household items had a sexual theme. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the sexual mores of the ancient Roman culture of the time were much more liberal than most present-day cultures, although much of what might seem to us to be erotic imagery (eg oversized phalluses) was in fact fertility-imagery. This clash of cultures led to an unknown number of discoveries being hidden away again. For example, a wall fresco which depicted Priapus, the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged penis, was covered with plaster (and, as Karl Schefold explains (p. 134), even the older reproduction below was locked away "out of prudishness" and only opened on request) and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall. The Times reported in 2006 "Erotic frescoes put Pompeii brothel on the tourist map".

In 1819, when King Francis I of Naples visited the Pompeii exhibition at the National Museum with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a secret cabinet, accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, it was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still only allowed entry to the once secret cabinet in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.

Roman decadence

Roman decadence defines the gradual and moral decline in the ancient Roman republican values of family, farming, virtus, and dignitas.

Some contemporary critics of Roman decadence, such as Cato the Younger, attributed its rise to the influence of the Hellenistic philosophy epicureanism, while modern historians such as Edward Gibbon ( The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, was published in six volumes between 1776 and 1788.) and Cyril Robinson also attribute increasing Roman affluence and the pacifying luxury it afforded.

According to Edward Gibbon, the root of the decadence may lie in the political system. Especially mentioned is the lack of clear rules of succession. A significant number of successions involved bribing the army to be elected emperor, and a civil war between different declared emperors. This resulted in higher taxes and frequent destruction that provoked the apathy of the elite.

More controversially, the early history of the Christian church is also mentioned as a cause of decadence. The early Roman Empire was usually tolerant of the religion of the people conquered, and tried to preserve peace amongst its subjects. After the conversion of most of the Empire to Christianity, religious issues took a proiminent place in the political debate, sometimes leading to civil wars and later persecutions.

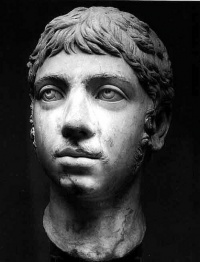

Roman sexuality

Sexuality in ancient Rome generally lacked the modern categories of "heterosexual" or "homosexual." Instead, the differentiating characteristic was activity versus passivity, or penetrating versus penetrated.

Male Sexuality Romans thought that men should be the active participant in all forms of love. Male passivity symbolized a loss of manliness, the most prized Roman virtue. This is in stark contrast to the Pederasty in ancient Greece, in which young boys became men through relations with adult males. It was socially and legally acceptable for Roman men to have sex with both female and male prostitutes as well as young slaves, as long as the Roman man was the active partner. Laws such as the Lex Scantina, Lex Iulia, and Lex Iulia de vi publica regulated against homosexual love between free men and boys, but these laws were frequently violated and rarely enforced, with men performing the passive role and vice versa. If the laws were ever enforced, the partner punished would be the passive male, not the active male. A man who liked to be penetrated was called "pathic", roughly translated as "bottom" in modern sex terminology, and was considered to be weak and feminine.

Female Sexuality Women were not granted freedom of sexuality. Men considered female homosexuality disgusting and dangerous. A woman who wanted to be an active partner in intercourse was a "tribade" (the meaning of which has now changed).

Homosexuality in Literature Few accounts of love between women exist through the eyes of women, so we only know the viewpoint of Roman men. Multiple ancient Roman authors wrote about love affairs between men, including Catullus, Tibullus, Propertius, Lucretius, Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. Catullus wrote of his love for the young man Juventius, while Tibullus dedicated two elegies to his lover Marathus and wrote particularly about how devastated he was that Marathus had left him for a woman.

Symbols

One of the symbols of Rome is the Colosseum (70-80), the largest amphitheatre ever built in the Roman Empire. Originally capable of seating 50,000 spectators, it was used for gladiatorial combat. The list of the very important monuments of ancient Rome includes the Roman Forum, the Domus Aurea, the Pantheon, the Trajan's Column, the Trajan's Market, the Catacombs of Rome, the Circus Maximus, the Baths of Caracalla, the Arch of Constantine, the Pyramid of Cestius, the Bocca della Verità.