Emblem book

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

| Revision as of 09:50, 11 July 2013 Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) ← Previous diff |

Current revision Jahsonic (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| - | [[Image:From the Waking Dream book.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[Adspectus Incauti Dispendium]]'' (1601), woodblock title page from the ''[[Veridicus Christianus]]''.]] | + | [[Image:Iconologia.jpg|thumb|left|200px|''[[Iconologia]]'' (1593) by Cesare Ripa]] |

| - | [[Image:Iconologia.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[Iconologia]]'' (1593) by [[Cesare Ripa]] was an [[emblem book]] highly influential on [[Baroque]] imagery]] | + | {| class="toccolours" style="float: left; margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 2em; font-size: 85%; background:#c6dbf7; color:black; width:30em; max-width: 40%;" cellspacing="5" |

| + | | style="text-align: left;" | | ||

| + | But if someone asks me what [[emblem book|Emblemata]] really are? I will reply to him, that they are mute images, and nevertheless speaking: insignificant matters, and none the less of importance: ridiculous things, and nonetheless not without wisdom [...]--[[Jacob Cats]], ''[[Voor-reden over de Proteus, of Minne-beelden, verandert in sinne-beelden]]'' | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "Among the scholarly works on the fantastique, ''[[Au cœur du fantastique]]'' is one of the few to give ample attention to emblem books." | ||

| + | <hr> | ||

| + | "As a suitable Frontispiece the portraits are presented of five celebrated authors of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries : one a German — [[Sebastian Brant|Sebastian Brandt]] ; three Italian — [[Andrea Alciato |Andrew Alciat]], [[Paolo Giovio]], and [[Achille Bocchi |Achilles Bocchius]] ; and one from Hungary — [[János Zsámboky |John Sambucus]]."--''[[Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers]]'' (1869) by Henry Green | ||

| + | |} | ||

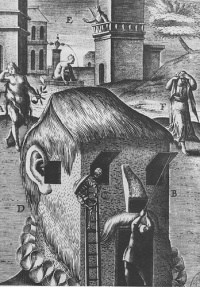

| + | [[Image:From the Waking Dream book.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''[[Adspectus Incauti Dispendium]]'' (1601), woodblock title page from the ''Veridicus Christianus'']] | ||

| {{Template}} | {{Template}} | ||

| - | :''[[emblemata amatoria]], [[Hypnerotomachia Poliphili]]'' | ||

| - | '''Emblem books''' are a particular style of [[illustrated book]] developed in [[Europe]] during the [[16th century in literature|16th]] and [[17th century in literature|17th centuries]], normally containing about one hundred combinations of pictures and text. | ||

| - | Scholars differ on the key question of whether the actual [[emblem]]s in question are the visual images, the accompanying texts, or the combination of the two. This is understandable, given that the first emblem book, the [[Emblemata]] of [[Andrea Alciato]], was first issued in an [[unauthorized edition]] in which the [[woodcut]]s were chosen by the printer without any input from the author, who had circulated the texts in unillustrated manuscript form. Some early emblem books were unillustrated, particularly those issued by the French printer Denis de Harsy. With time, however, the reading public came to expect emblem books to contain picture-text combinations. Each combination consisted of a [[woodcut]] or [[engraving]] accompanied by one or more short texts, intended to inspire their readers to reflect on a general [[moral lesson]] derived from the reading of both picture and text together. The picture was subject to numerous interpretations: only by reading the text could a reader be certain which meaning was intended by the author. Thus the books are closely related to the personal symbolic picture-text combinations called [[personal device]]s, known in Italy as ''imprese'' and in France as ''devises''. | + | '''Emblem books''' are a category of mainly didactic [[illustrated book]]s printed in [[Europe]] during the 16th and [[17th century in literature|17th centuries]], typically containing a number of [[emblematic]] images with [[explanatory]] text. A well-known emblem is ''[[Nutrix ejus terra est]]'' (The Earth is his Nurse), the second [[emblem]] from the [[emblem book]] ''[[Atalanta Fugiens]]'' (1617). |

| - | Emblem books, both [[secular]] and [[religious]], attained enormous popularity throughout continental Europe, though in [[Great Britain|Britain]] they never captured the imagination of readers to the same extent. The books were especially numerous in the [[Netherlands]], [[Belgium]], [[Germany]], and [[France]]. [[Andrea Alciato]] wrote the epigrams contained in the first and most widely disseminated emblem book, the ''[[Emblemata]]'', published by Heinrich Steyner in 1531 in [[Augsburg]]. Another influential illustrated book was [[Iconologia|Cesare Ripa's ''Iconologia'']], first published in 1593, though it is not properly speaking an emblem book but a collection of erudite allegories. | + | Scholars differ on the key question of whether the actual [[emblem]]s in question are the visual images, the accompanying texts, or the combination of the two. This is understandable, given that the first emblem book, the [[Emblemata]] of [[Andrea Alciato]], was first issued in an unauthorized edition in which the [[woodcut]]s were chosen by the printer without any input from the author, who had circulated the texts in unillustrated manuscript form. Some early emblem books were unillustrated, particularly those issued by the French printer Denis de Harsy. With time, however, the reading public came to expect emblem books to contain picture-text combinations. Each combination consisted of a [[woodcut]] or [[engraving]] accompanied by one or more short texts, intended to inspire their readers to reflect on a general [[morality|moral]] lesson derived from the reading of both picture and text together. The picture was subject to numerous interpretations: only by reading the text could a reader be certain which meaning was intended by the author. Thus the books are closely related to the personal symbolic picture-text combinations called [[personal device]]s, known in Italy as ''imprese'' and in France as ''devises''. |

| + | |||

| + | Emblem books, both [[secular]] and [[religious]], attained enormous popularity throughout continental Europe, though in [[Great Britain|Britain]] they did not capture the imagination of readers to quite the same extent. The books were especially numerous in the [[Netherlands]], [[Belgium]], [[Germany]], and [[France]]. [[Andrea Alciato]] wrote the epigrams contained in the first and most widely disseminated emblem book, the ''[[Emblemata]]'', published by Heinrich Steyner in 1531 in [[Augsburg]]. Another influential illustrated book was [[Cesare Ripa]] ''[[Iconologia]]'', first published in 1593, though it is not properly speaking an emblem book but a collection of erudite allegories. Two English emblem books were published in 1635, the famous ''Emblems'' of [[Francis Quarles]], and [[George Wither]]'s ''A collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne''. Many emblematic works borrowed plates or texts (or both) from earlier exemplars, as was the case with [[Geoffrey Whitney]]'s ''[[Choice of Emblemes]]'', a compilation which chiefly used the resources of the [[Plantin Press]] in Leyden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Early European studies of [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]], like that of [[Athanasius Kircher]], assumed that the hieroglyphs were emblems, and imaginatively interpreted them accordingly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Origins== | ||

| + | Emblem books are collections of sets of three elements: an icon or image, a motto, and text explaining the connection between the image and motto. The text ranged in length from a few lines of verse to pages of prose. Emblem books descended from medieval bestiaries that explained the importance of animals, proverbs, and fables. In fact, writers often drew inspiration from Greek and Roman sources such as [[Aesop's Fables]] and [[Plutarch's Lives]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Definition == | ||

| + | |||

| + | Scholars differ on the key question of whether the actual [[emblem]]s in question are the visual images, the accompanying texts, or the combination of the two. This is understandable, given that first emblem book, the ''[[Emblemata]]'' of [[Andrea Alciato]], was first issued in an unauthorized edition in which the [[woodcut]]s were chosen by the printer without any input from the author, who had circulated the texts in unillustrated manuscript form. It contained around a hundred short verses in Latin. One image it depicted was the lute which symbolized the need for harmony instead of warfare in the city-states of Italy. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some early emblem books were unillustrated, particularly those issued by the French printer Denis de Harsy.<!-- As of 3/2015, there is not even a French article on him.--> With time, however, the reading public came to expect emblem books to contain picture-text combinations. Each combination consisted of a [[woodcut]] or [[engraving]] accompanied by one or more short texts, intended to inspire their readers to reflect on a general [[morality|moral]] lesson derived from the reading of both picture and text together. The picture was subject to numerous interpretations: only by reading the text could a reader be certain which meaning was intended by the author. Thus the books are closely related to the personal symbolic picture-text combinations called [[personal device]]s, known in Italy as ''imprese'' and in France as ''devises''. Many of the symbolic images present in emblem books were used in other contexts, on clothes, furniture, street signs, and the facades of buildings. For instance, a sword and scales symbolized death. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Miscellany == <!-- I'm not happy about the name of this headline, but I couldn't find a better name, and we need one to mark the end of the "Definition" section. --> | ||

| + | Emblem books, both [[secular]] and [[religious]], attained enormous popularity throughout continental Europe, though in Britain they did not capture the imagination of readers to quite the same extent. The books were especially numerous in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and France. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Many emblematic works borrowed plates or texts (or both) from earlier exemplars, as was the case with [[Geoffrey Whitney]]'s ''Choice of Emblemes'', a compilation which chiefly used the resources of the [[Plantin Press]] in Leyden. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Early European studies of [[Egyptian hieroglyphs]], like that of [[Athanasius Kircher]], assumed that the hieroglyphs were emblems, and imaginatively interpreted them accordingly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | A similar collection of emblems, but not in book form, is [[Lady Drury's Closet]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Timeline == | ||

| + | <!-- All information in the following table refers to the first edition, unless specified differently. Sources are the links; usually en:Wikipedia, mostly the article on the author. Theme may sometimes be OR, but it should help with sorting. --> | ||

| + | {|class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| + | !Author or compilator!!Title!!Engraver, Illustrator!!Publisher!!Loc.!!Publ.!!Theme!!# of Embl.!!Lang. !!Notes | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Alciato"|[[Andrea Alciato]]||''[[Emblemata]]''||data-sort-value="Schäufelin"|probably [[Hans Leonhard Schäufelein|Hans Schäufelin]] after [[Jörg Breu the Elder]]||data-sort-value="Steyner"|Heinrich Steyner||data-sort-value="de.Augsburg"|Augsburg||1531||||104|||| the first and most widely disseminated emblem book. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="de La Perriè"|[[Guillaume de La Perrière]]||''[[Theatre de bons engines]]''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="fr.Paris"|Paris||1539|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Bocchi"|[[Achille Bocchi]]||''Symbolicarum quaestionum de universo genere''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1555|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Faerno"|[[Gabriele Faerno]]||''Centum Fabulae ''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1563||fables||100||la|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Zsámboky"|[[János Zsámboky]]||''Emblemata cum aliquot nummis antiqui operis''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="at.Vienna"|Vienna||1564|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Hoefnagel"|[[Joris Hoefnagel]]||''Patientia''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="uk.London"|London||1569||moral|||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="de Monteney"|Georgette de Monteney||''Emblemes, ou Devises Chrestiennes''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de Tournes"|[[Jean de Tournes]] ?||data-sort-value="fr.Lyon"|Lyon||1571|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Reusner"|Nicolaus Reusner||''Emblemata''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Frankfurt"|Frankfurt||1581|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Whitney"|[[Geoffrey Whitney]]||''[[Choice of Emblemes]]''||data-sort-value="zzz(various)zz"|(various)||data-sort-value="zzzPlantinzz"|Plantin||data-sort-value="nl.Leiden"|Leiden||1586||||248|||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Ripa"|[[Cesare Ripa]]||''Iconologia''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="it.Rome"|Rome||1593||||||||not properly speaking an emblem book but a collection of erudite allegories. | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Taurellus"|Nicolaus Taurellus||''Emblemata Physico Ethica''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Nuremberg"|Nuremberg||1595|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Heinsius"|Daniel Heinsius||''Quaeris quid sit amor''||data-sort-value="de Gheyn II"|Jakob de Gheyn II||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1601||love||||||first emblem book dedicated to love; later name "''[[Emblemata amatoria]]''" | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Typotius"|[[Jacobus Typotius]]||''Symbola Divina et Humana''||data-sort-value="Sadeler II"|[[Aegidius Sadeler II]]||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="at.Prague"|Prague||1601|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="van Veen"|[[Otto van Veen]]||data-sort-value="Amorum Emblemata"|''Amorum Emblemata'' | ||

| + | ||data-sort-value="van Veen"|Otto van Veen||data-sort-value="zzzSwingeniuszz"|Henricus Swingenius||data-sort-value="nl.Antwerp"|Antwerp||1608||love||124||la||Published in more than one multilingual edition, with variants including French, Dutch, English, Italian and Spanish | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Corneliszoon"|Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft||''[[Emblemata Amatoria]]''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1611||love||||||Not to be confused with ''Quaeris quid sit amor'', which was republished under the same name. <!-- per [[Daniel Heinsius]] and [[:nl:Emblemataboek]] --> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Rollenhagen"|[[Gabriel Rollenhagen]] ||''Nucleus emblematum''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Hildesheim"|Hildesheim||1611|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="van Veen"|Otto van Veen||''Amoris divini emblemata''||data-sort-value="van Veen"|Otto van Veen||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1615||divine love|||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Heinsius"|Daniel Heinsius||''Het Ambacht van Cupido''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Leiden"|Leiden||1615|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Maier"|[[Michael Maier]]||''[[Atalanta Fugiens]]''||data-sort-value="Merian"|[[Matthias Merian]]||data-sort-value="Theodor de B"|Johann Theodor de Bry||data-sort-value="de.Oppenheim"|Oppenheim||1617||alchemy||50||la,de||Also contains a fugue for each emblem | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Iselburg"|{{Interlanguage link multi|Peter Iselburg|de}}||''Aula Magna Curiae Noribergensis Depicta''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Nuremberg"|Nuremberg||1617||||32||la,de|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cramer,"|[[Daniel Cramer]], {{Interlanguage link multi|Conrad Bachmann|de|3=Konrad Bachmann (Literaturwissenschaftler)}}||''Emblemata Sacra''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1617||||40|||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="zzz(various)zz"|(various)||''{{Interlanguage link multi|Thronus Cupidinis|nl}}''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1618|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cats"|[[Jacob Cats]]||''Silenus Alcibiadis, sive Proteus''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands?)||1618|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cats"|Jacob Cats||''Sinn’en Minne-beelden''||data-sort-value="van de Venne"|Adriaen van de Venne||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1618||||||||Two alternative explanations for each emblem, one related to mind (Sinnn), the other to love (Minne). | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Zincgref"|Julius Wilhelm Zincgref||''Emblemata''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Frankfurt"|Frankfurt||1619|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cats"|Jacob Cats||''Monita Amoris Virginei''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Amsterdam"|Amsterdam||1620||moral||45||||for women | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Custos"|[[Raphael Custos]]||''Emblemata amoris''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1622|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="de Brune"|{{Interlanguage link multi|Johan de Brune|nl}}||''[[Emblemata of Zinne-werck]]''||data-sort-value="van de Venne"|[[Adriaen van de Venne]]||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Amsterdam"|Amsterdam||1624||||51|||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Hugo"|[[Herman Hugo]]||''Pia desideria''||data-sort-value="à Bolswert"|[[Boetius à Bolswert]]||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Antwerp"|Antwerp||1624||||||la||42 Latin editions; widely translated | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Stolz von St"|[[Daniel Stolz von Stolzenberg]]||''Viridarium Chymicum''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="at.Prague?"|Prague?||1624||alchemy|||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Heyns"|[[Zacharias Heyns]]||''Emblemata''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands?)||1625|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Jennis"|[[Lucas Jennis]]||''[[Musaeum Hermeticum]]''|| ||||data-sort-value="de.Frankfurt"|Frankfurt||1625||alchemy||||la|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cats"|Jacob Cats||''Proteus ofte Minne-beelden''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Rotterdam"|Rotterdam||1627|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="van Haeften"|[[Benedictus van Haeften]]||''Schola cordis''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1629|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cramer"|Daniel Cramer||''Emblemata moralia nova''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="de.Frankfurt"|Frankfurt||1630|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="a Burgundia"|[[Antonius a Burgundia]]||''Linguae vitia et remedia''||data-sort-value="Neefs &"|[[Jacob Neefs]], [[Andries Pauwels]]||data-sort-value="Cnobbaert"|[[Joannes Cnobbaert]]||data-sort-value="nl.Antwerp"|Antwerp||1631||||45|||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Cats"|Jacob Cats||''Spiegel van den Ouden ende Nieuwen Tijdt''||data-sort-value="van de Venne"|Adriaen van de Venne||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands?)||1632|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Hawkins (Jes"|[[Henry Hawkins (Jesuit)|Henry Hawkins]]||''Partheneia Sacra''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1633|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Luzvic"|[[Etienne Luzvic]]||''Le cœur dévot''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1634||||||||translated into English as ''The Devout Heart'' | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Wither "|[[George Wither]] ||''A collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1635|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Quarles"|[[Francis Quarles]]||''Emblems''||data-sort-value="Marshall &"|[[William Marshall (illustrator)|William Marshall]] & al.||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1635|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Harmenszoon "|[[Jan Harmenszoon Krul]]||''Minne-spiegel ter Deughden''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.Amsterdam"|Amsterdam||1639|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Bolland"|[[Jean Bolland]], [[Sidronius Hosschius]]||''Imago primi saeculi Societatis Iesu a provincia Flandro-Belgica ejusdem Societatis repraesentata''||data-sort-value="Marshall"|[[Cornelis Galle the Elder]]||data-sort-value="plan"|[[Plantin Press]]||data-sort-value="antwerr"|Antwerp ||1640||A Jesuit emblem book illustrating the history of the Jesuit order in the Southern Netherlands|||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="de Saavedra "|[[Diego de Saavedra Fajardo]]||''Empresas Políticas''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzz"| ||1640|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="zzz(anonymous)zz"|(anonymous)||''[[Devises et emblemes d'amour]]'' | ||

| + | ||data-sort-value="Flamen"|Albert Flamen||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="fr.Paris"|Paris||1648|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Picinelli"|[[Filippo Picinelli]]||''Il mondo simbolico''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="it.Milan"|Milan||1653||encyclopedic||||it||1000 pages | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Gambart"|[[Adrien Gambart]]||''La Vie symbolique du bienheureux François de Sales''||data-sort-value="Flamen"|Albert Flamen||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="fr.Paris"|Paris||1664|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Luyken"|[[Jan Luyken]]||''Jesus en de ziel''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands)||1678|||||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Romaguera"|[[Josep Romaguera]]||''[[Atheneo de Grandesa]]''||data-sort-value="zzz(anonymous)zz"|(anonymous)||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="es.Barcelona"|Barcelona||1681||||15||ca|| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||''Livre curieux et très utile pour les sçavans, et artistes''||data-sort-value="Verrien"|Nicolas Verrien||data-sort-value="de La Feuill"|Daniel de La Feuille||data-sort-value="nl.Amsterdam"|Amsterdam||1691||encyclopedic||||||<!-- from [[:fr:Nicolas Verrien]] --> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Luyken"|Jan Luyken||''[[Het Menselyk Bedryf ("The Book of Trades")|Het Menselyk Bedryf<br>("The Book of Trades")]]''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands?)||1694||trades|||||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="Boschius"|[[Jacobus Boschius]]||''Symbolographia sive De Arte Symbolica sermones septem''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="Beucard"|Caspar Beucard||data-sort-value="de.Augsburg"|Augsburg||1701||encyclopedic||3347|||| | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |data-sort-value="de Hooghe"|[[Romeyn de Hooghe]]||''[[Hieroglyphica of Merkbeelden der oude volkeren]]''||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="zzzzz"| ||data-sort-value="nl.zzz"|(Netherlands?)||1735|||||||| | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | {{Reflist|group=n}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Authors and artists famous for emblem books == | ||

| + | * [[Andrea Alciato]] (1492 – 1550) | ||

| + | * [[Guillaume de La Perrière]] (1499/1503 – 1565) | ||

| + | * [[Georgette de Montenay]] (1540 – 1581) | ||

| + | * [[Otto van Veen]] (c.1556 – 1629) | ||

| + | * [[Jacob Cats]] (1577 – 1660) | ||

| + | * [[Albert Flamen]] (c.1620 – after 1669) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Selected list of illustrations== | ||

| + | *''[[Nutrix ejus terra est]]''[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atalanta_Fugiens_-_Emblem_2d.jpg] (The Earth is his Nurse) is the second [[emblem]] from the ''[[Atalanta Fugiens]]''[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Atalanta_Fugiens] | ||

| + | ==Pages linking in as of Dec 2021== | ||

| + | [[Achille Bocchi]], [[Adriaen van de Venne]], [[Aesop's Fables]], [[Albert Flamen]], [[Andrea Alciato]], [[Anna Visscher]], [[Antoine de Bourgogne]], [[Arnold Houbraken]], [[Atalanta Fugiens]], [[Atheneo de Grandesa]], [[Barthélemy Aneau]], [[Bernard Salomon]], [[Between Scylla and Charybdis]], [[Blason]], [[Boetius à Bolswert]], [[Cesare Ripa]], [[Christophe Plantin]], [[Cornelis de Bie]], [[Daniel Cramer]], [[Daniël Heinsius]], [[Daniel Stolz von Stolzenberg]], [[Denis Janot]], [[Diego de Saavedra Fajardo]], [[Dutch Golden Age painting]], [[Emblem]], [[Emblemata of Zinne-werck]], [[Emblemata]], [[English embroidery]], [[European dragon]], [[Feast of the Gods (art)]], [[Fight with Cudgels]], [[Four continents]], [[Francis Quarles]], [[Gabriël Metsu]], [[Gabriel Rollenhagen]], [[Gabriele Faerno]], [[Genre art]], [[Genre painting]], [[Geoffrey Whitney]], [[George Richard Savage Nassau]], [[George Wither]], [[Georgette de Montenay]], [[Gerrit Dou]], [[Gilles Corrozet]], [[Glossary of literary terms]], [[Great Seal of the United States]], [[Guillaume de La Perrière]], [[Guillaume Rouillé]], [[Hans van der Hellen]], [[Henry Hawkins (Jesuit)]], [[Heraldic badge]], [[Hercules and the Wagoner]], [[Herman Hugo]], [[Het Menselyk Bedryf ("The Book of Trades")]], [[Historia animalium (Gessner book)]], [[Iconography]], [[Invidia]], [[Jacob Cats]], [[Jacob de Bie]], [[Jacob Jordaens]], [[Jacob Neefs]], [[Jacobus Typotius]], [[Jan Harmenszoon Krul]], [[Janus Cornarius]], [[Jean Baudoin (translator)]], [[Johann Vogel (poet)]], [[Joris Hoefnagel]], [[Josep Romaguera]], [[Joseph Brooks Yates]], [[La Decadència]], [[Lady Drury's Closet]], [[Lady Standing at a Virginal]], [[Liberty (personification)]], [[Liberty pole]], [[Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder]], [[Marian art in the Catholic Church]], [[Martin Droeshout]], [[Michael Maier]], [[Michel Le Nobletz]], [[Miser]], [[Muses]], [[Northern Mannerism]], [[Otto van Veen]], [[Painted frieze of the Bodleian Library]], [[Pandora]], [[Pandora's box]], [[Personification of the Americas]], [[Personification]], [[Philips van Mallery]], [[Portraiture of Elizabeth I]], [[Raphael Custos]], [[Real tennis]], [[Romeyn de Hooghe]], [[Rosemary Freeman]], [[Rossend Castle]], [[Royal entry]], [[Sadeler family]], [[Samuel Daniel]], [[Schouwen-Duiveland]], [[Self-Portrait with a Sunflower]], [[Silvester Petra Sancta]], [[Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus]], [[The Allegory of Faith]], [[The Astrologer who Fell into a Well]], [[The Bear and the Bees]], [[The Beaver (fable)]], [[The Blind Man and the Lame]], [[The Cock, the Dog and the Fox]], [[The Crow and the Snake]], [[The Dog and Its Reflection]], [[The Dog in the Manger]], [[The drowned woman and her husband]], [[The Eagle and the Beetle]], [[The Eagle Wounded by an Arrow]], [[The Elm and the Vine]], [[The Embarrassment of Riches]], [[The Fox and the Grapes]], [[The Fox and the Lion]], [[The Fox and the Mask]], [[The Fox and the Sick Lion]], [[The Frog and the Mouse]], [[The Frogs Who Desired a King]], [[The Gourd and the Palm-tree]], [[The Hare in flight]], [[The Hedgehog and the Snake]], [[The Man who Runs after Fortune]], [[The Monkey and the Cat]], [[The Mouse and the Oyster]], [[The North Wind and the Sun]], [[The Oak and the Reed]], [[The Old Man and his Sons]], [[The Old Woman and the Wine-jar]], [[The Pilgrim's Progress]], [[The Quack Doctor]], [[The Satyr and the Traveller]], [[The Tortoise and the Hare]], [[The Walnut Tree]], [[Thomas Jenner (publisher)]], [[Walther Damery]], [[Washing the Ethiopian White]], [[William Marshall (illustrator)]], [[Winged lion]], [[Woodcut]], [[Xanthippe]], [[Yorick]], [[Zacharias Heyns]], [[Zeus and the Tortoise]] | ||

| - | Early European studies of [[Egyptian hieroglyphics]], like that of [[Athanasius Kircher]], assumed that the hieroglyphics were emblems, and imaginatively interpreted them accordingly. | ||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| + | *[[16th century literature]] | ||

| + | *[[17th century literature]] | ||

| + | *[[Devises héroïques]] | ||

| *[[Lady Drury's Closet]] | *[[Lady Drury's Closet]] | ||

| *[[Georgette de Montenay]] | *[[Georgette de Montenay]] | ||

| - | *[[Guillaume de La Perrière]] | + | *''[[Hypnerotomachia Poliphili]]'' |

| - | ==Selected list of illustrations== | + | *[[Full text of "Iconologia, or, Moral emblems"]] |

| - | *''[[Nutrix ejus terra est]]''[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atalanta_Fugiens_-_Emblem_2d.jpg] (The Earth is his Nurse) is the second [[emblem]] from the ''[[Atalanta Fugiens]]''[http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Atalanta_Fugiens] | + | *''[[Emblemata Amatoria]]'' (1611) by P.C. Hooft |

| + | *[[Illustrated fiction]] | ||

| + | *''[[La Morosophie]]'' (Macé Bonhomme, 1553) is a book by [[Guillaume de La Perrière]] | ||

| + | *[[Emblem books of the Low Countries]] | ||

| {{GFDL}} | {{GFDL}} | ||

Current revision

|

But if someone asks me what Emblemata really are? I will reply to him, that they are mute images, and nevertheless speaking: insignificant matters, and none the less of importance: ridiculous things, and nonetheless not without wisdom [...]--Jacob Cats, Voor-reden over de Proteus, of Minne-beelden, verandert in sinne-beelden "Among the scholarly works on the fantastique, Au cœur du fantastique is one of the few to give ample attention to emblem books." "As a suitable Frontispiece the portraits are presented of five celebrated authors of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries : one a German — Sebastian Brandt ; three Italian — Andrew Alciat, Paolo Giovio, and Achilles Bocchius ; and one from Hungary — John Sambucus."--Shakespeare and the Emblem Writers (1869) by Henry Green |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Emblem books are a category of mainly didactic illustrated books printed in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries, typically containing a number of emblematic images with explanatory text. A well-known emblem is Nutrix ejus terra est (The Earth is his Nurse), the second emblem from the emblem book Atalanta Fugiens (1617).

Scholars differ on the key question of whether the actual emblems in question are the visual images, the accompanying texts, or the combination of the two. This is understandable, given that the first emblem book, the Emblemata of Andrea Alciato, was first issued in an unauthorized edition in which the woodcuts were chosen by the printer without any input from the author, who had circulated the texts in unillustrated manuscript form. Some early emblem books were unillustrated, particularly those issued by the French printer Denis de Harsy. With time, however, the reading public came to expect emblem books to contain picture-text combinations. Each combination consisted of a woodcut or engraving accompanied by one or more short texts, intended to inspire their readers to reflect on a general moral lesson derived from the reading of both picture and text together. The picture was subject to numerous interpretations: only by reading the text could a reader be certain which meaning was intended by the author. Thus the books are closely related to the personal symbolic picture-text combinations called personal devices, known in Italy as imprese and in France as devises.

Emblem books, both secular and religious, attained enormous popularity throughout continental Europe, though in Britain they did not capture the imagination of readers to quite the same extent. The books were especially numerous in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and France. Andrea Alciato wrote the epigrams contained in the first and most widely disseminated emblem book, the Emblemata, published by Heinrich Steyner in 1531 in Augsburg. Another influential illustrated book was Cesare Ripa Iconologia, first published in 1593, though it is not properly speaking an emblem book but a collection of erudite allegories. Two English emblem books were published in 1635, the famous Emblems of Francis Quarles, and George Wither's A collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne. Many emblematic works borrowed plates or texts (or both) from earlier exemplars, as was the case with Geoffrey Whitney's Choice of Emblemes, a compilation which chiefly used the resources of the Plantin Press in Leyden.

Early European studies of Egyptian hieroglyphs, like that of Athanasius Kircher, assumed that the hieroglyphs were emblems, and imaginatively interpreted them accordingly.

Contents |

Origins

Emblem books are collections of sets of three elements: an icon or image, a motto, and text explaining the connection between the image and motto. The text ranged in length from a few lines of verse to pages of prose. Emblem books descended from medieval bestiaries that explained the importance of animals, proverbs, and fables. In fact, writers often drew inspiration from Greek and Roman sources such as Aesop's Fables and Plutarch's Lives.

Definition

Scholars differ on the key question of whether the actual emblems in question are the visual images, the accompanying texts, or the combination of the two. This is understandable, given that first emblem book, the Emblemata of Andrea Alciato, was first issued in an unauthorized edition in which the woodcuts were chosen by the printer without any input from the author, who had circulated the texts in unillustrated manuscript form. It contained around a hundred short verses in Latin. One image it depicted was the lute which symbolized the need for harmony instead of warfare in the city-states of Italy.

Some early emblem books were unillustrated, particularly those issued by the French printer Denis de Harsy. With time, however, the reading public came to expect emblem books to contain picture-text combinations. Each combination consisted of a woodcut or engraving accompanied by one or more short texts, intended to inspire their readers to reflect on a general moral lesson derived from the reading of both picture and text together. The picture was subject to numerous interpretations: only by reading the text could a reader be certain which meaning was intended by the author. Thus the books are closely related to the personal symbolic picture-text combinations called personal devices, known in Italy as imprese and in France as devises. Many of the symbolic images present in emblem books were used in other contexts, on clothes, furniture, street signs, and the facades of buildings. For instance, a sword and scales symbolized death.

Miscellany

Emblem books, both secular and religious, attained enormous popularity throughout continental Europe, though in Britain they did not capture the imagination of readers to quite the same extent. The books were especially numerous in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, and France.

Many emblematic works borrowed plates or texts (or both) from earlier exemplars, as was the case with Geoffrey Whitney's Choice of Emblemes, a compilation which chiefly used the resources of the Plantin Press in Leyden.

Early European studies of Egyptian hieroglyphs, like that of Athanasius Kircher, assumed that the hieroglyphs were emblems, and imaginatively interpreted them accordingly.

A similar collection of emblems, but not in book form, is Lady Drury's Closet.

Timeline

| Author or compilator | Title | Engraver, Illustrator | Publisher | Loc. | Publ. | Theme | # of Embl. | Lang. | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrea Alciato | Emblemata | probably Hans Schäufelin after Jörg Breu the Elder | Heinrich Steyner | Augsburg | 1531 | 104 | the first and most widely disseminated emblem book. | ||

| Guillaume de La Perrière | Theatre de bons engines | Paris | 1539 | ||||||

| Achille Bocchi | Symbolicarum quaestionum de universo genere | 1555 | |||||||

| Gabriele Faerno | Centum Fabulae | 1563 | fables | 100 | la | ||||

| János Zsámboky | Emblemata cum aliquot nummis antiqui operis | Vienna | 1564 | ||||||

| Joris Hoefnagel | Patientia | London | 1569 | moral | |||||

| Georgette de Monteney | Emblemes, ou Devises Chrestiennes | Jean de Tournes ? | Lyon | 1571 | |||||

| Nicolaus Reusner | Emblemata | Frankfurt | 1581 | ||||||

| Geoffrey Whitney | Choice of Emblemes | (various) | Plantin | Leiden | 1586 | 248 | |||

| Cesare Ripa | Iconologia | Rome | 1593 | not properly speaking an emblem book but a collection of erudite allegories. | |||||

| Nicolaus Taurellus | Emblemata Physico Ethica | Nuremberg | 1595 | ||||||

| Daniel Heinsius | Quaeris quid sit amor | Jakob de Gheyn II | (Netherlands) | 1601 | love | first emblem book dedicated to love; later name "Emblemata amatoria" | |||

| Jacobus Typotius | Symbola Divina et Humana | Aegidius Sadeler II | Prague | 1601 | |||||

| Otto van Veen | Amorum Emblemata | data-sort-value="van Veen"|Otto van Veen | Henricus Swingenius | Antwerp | 1608 | love | 124 | la | Published in more than one multilingual edition, with variants including French, Dutch, English, Italian and Spanish |

| Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft | Emblemata Amatoria | (Netherlands) | 1611 | love | Not to be confused with Quaeris quid sit amor, which was republished under the same name. | ||||

| Gabriel Rollenhagen | Nucleus emblematum | Hildesheim | 1611 | ||||||

| Otto van Veen | Amoris divini emblemata | Otto van Veen | (Netherlands) | 1615 | divine love | ||||

| Daniel Heinsius | Het Ambacht van Cupido | Leiden | 1615 | ||||||

| Michael Maier | Atalanta Fugiens | Matthias Merian | Johann Theodor de Bry | Oppenheim | 1617 | alchemy | 50 | la,de | Also contains a fugue for each emblem |

| Template:Interlanguage link multi | Aula Magna Curiae Noribergensis Depicta | Nuremberg | 1617 | 32 | la,de | ||||

| Daniel Cramer, Template:Interlanguage link multi | Emblemata Sacra | 1617 | 40 | ||||||

| (various) | Template:Interlanguage link multi | (Netherlands) | 1618 | ||||||

| Jacob Cats | Silenus Alcibiadis, sive Proteus | (Netherlands?) | 1618 | ||||||

| Jacob Cats | Sinn’en Minne-beelden | Adriaen van de Venne | (Netherlands) | 1618 | Two alternative explanations for each emblem, one related to mind (Sinnn), the other to love (Minne). | ||||

| Julius Wilhelm Zincgref | Emblemata | Frankfurt | 1619 | ||||||

| Jacob Cats | Monita Amoris Virginei | Amsterdam | 1620 | moral | 45 | for women | |||

| Raphael Custos | Emblemata amoris | 1622 | |||||||

| Template:Interlanguage link multi | Emblemata of Zinne-werck | Adriaen van de Venne | Amsterdam | 1624 | 51 | ||||

| Herman Hugo | Pia desideria | Boetius à Bolswert | Antwerp | 1624 | la | 42 Latin editions; widely translated | |||

| Daniel Stolz von Stolzenberg | Viridarium Chymicum | Prague? | 1624 | alchemy | |||||

| Zacharias Heyns | Emblemata | (Netherlands?) | 1625 | ||||||

| Lucas Jennis | Musaeum Hermeticum | Frankfurt | 1625 | alchemy | la | ||||

| Jacob Cats | Proteus ofte Minne-beelden | Rotterdam | 1627 | ||||||

| Benedictus van Haeften | Schola cordis | 1629 | |||||||

| Daniel Cramer | Emblemata moralia nova | Frankfurt | 1630 | ||||||

| Antonius a Burgundia | Linguae vitia et remedia | Jacob Neefs, Andries Pauwels | Joannes Cnobbaert | Antwerp | 1631 | 45 | |||

| Jacob Cats | Spiegel van den Ouden ende Nieuwen Tijdt | Adriaen van de Venne | (Netherlands?) | 1632 | |||||

| Henry Hawkins | Partheneia Sacra | 1633 | |||||||

| Etienne Luzvic | Le cœur dévot | 1634 | translated into English as The Devout Heart | ||||||

| George Wither | A collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Moderne | 1635 | |||||||

| Francis Quarles | Emblems | William Marshall & al. | 1635 | ||||||

| Jan Harmenszoon Krul | Minne-spiegel ter Deughden | Amsterdam | 1639 | ||||||

| Jean Bolland, Sidronius Hosschius | Imago primi saeculi Societatis Iesu a provincia Flandro-Belgica ejusdem Societatis repraesentata | Cornelis Galle the Elder | Plantin Press | Antwerp | 1640 | A Jesuit emblem book illustrating the history of the Jesuit order in the Southern Netherlands | |||

| Diego de Saavedra Fajardo | Empresas Políticas | 1640 | |||||||

| (anonymous) | Devises et emblemes d'amour | data-sort-value="Flamen"|Albert Flamen | Paris | 1648 | |||||

| Filippo Picinelli | Il mondo simbolico | Milan | 1653 | encyclopedic | it | 1000 pages | |||

| Adrien Gambart | La Vie symbolique du bienheureux François de Sales | Albert Flamen | Paris | 1664 | |||||

| Jan Luyken | Jesus en de ziel | (Netherlands) | 1678 | ||||||

| Josep Romaguera | Atheneo de Grandesa | (anonymous) | Barcelona | 1681 | 15 | ca | |||

| Livre curieux et très utile pour les sçavans, et artistes | Nicolas Verrien | Daniel de La Feuille | Amsterdam | 1691 | encyclopedic | ||||

| Jan Luyken | Het Menselyk Bedryf ("The Book of Trades") | (Netherlands?) | 1694 | trades | |||||

| Jacobus Boschius | Symbolographia sive De Arte Symbolica sermones septem | Caspar Beucard | Augsburg | 1701 | encyclopedic | 3347 | |||

| Romeyn de Hooghe | Hieroglyphica of Merkbeelden der oude volkeren | (Netherlands?) | 1735 |

Authors and artists famous for emblem books

- Andrea Alciato (1492 – 1550)

- Guillaume de La Perrière (1499/1503 – 1565)

- Georgette de Montenay (1540 – 1581)

- Otto van Veen (c.1556 – 1629)

- Jacob Cats (1577 – 1660)

- Albert Flamen (c.1620 – after 1669)

Selected list of illustrations

- Nutrix ejus terra est[1] (The Earth is his Nurse) is the second emblem from the Atalanta Fugiens[2]

Pages linking in as of Dec 2021

Achille Bocchi, Adriaen van de Venne, Aesop's Fables, Albert Flamen, Andrea Alciato, Anna Visscher, Antoine de Bourgogne, Arnold Houbraken, Atalanta Fugiens, Atheneo de Grandesa, Barthélemy Aneau, Bernard Salomon, Between Scylla and Charybdis, Blason, Boetius à Bolswert, Cesare Ripa, Christophe Plantin, Cornelis de Bie, Daniel Cramer, Daniël Heinsius, Daniel Stolz von Stolzenberg, Denis Janot, Diego de Saavedra Fajardo, Dutch Golden Age painting, Emblem, Emblemata of Zinne-werck, Emblemata, English embroidery, European dragon, Feast of the Gods (art), Fight with Cudgels, Four continents, Francis Quarles, Gabriël Metsu, Gabriel Rollenhagen, Gabriele Faerno, Genre art, Genre painting, Geoffrey Whitney, George Richard Savage Nassau, George Wither, Georgette de Montenay, Gerrit Dou, Gilles Corrozet, Glossary of literary terms, Great Seal of the United States, Guillaume de La Perrière, Guillaume Rouillé, Hans van der Hellen, Henry Hawkins (Jesuit), Heraldic badge, Hercules and the Wagoner, Herman Hugo, Het Menselyk Bedryf ("The Book of Trades"), Historia animalium (Gessner book), Iconography, Invidia, Jacob Cats, Jacob de Bie, Jacob Jordaens, Jacob Neefs, Jacobus Typotius, Jan Harmenszoon Krul, Janus Cornarius, Jean Baudoin (translator), Johann Vogel (poet), Joris Hoefnagel, Josep Romaguera, Joseph Brooks Yates, La Decadència, Lady Drury's Closet, Lady Standing at a Virginal, Liberty (personification), Liberty pole, Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder, Marian art in the Catholic Church, Martin Droeshout, Michael Maier, Michel Le Nobletz, Miser, Muses, Northern Mannerism, Otto van Veen, Painted frieze of the Bodleian Library, Pandora, Pandora's box, Personification of the Americas, Personification, Philips van Mallery, Portraiture of Elizabeth I, Raphael Custos, Real tennis, Romeyn de Hooghe, Rosemary Freeman, Rossend Castle, Royal entry, Sadeler family, Samuel Daniel, Schouwen-Duiveland, Self-Portrait with a Sunflower, Silvester Petra Sancta, Sine Cerere et Baccho friget Venus, The Allegory of Faith, The Astrologer who Fell into a Well, The Bear and the Bees, The Beaver (fable), The Blind Man and the Lame, The Cock, the Dog and the Fox, The Crow and the Snake, The Dog and Its Reflection, The Dog in the Manger, The drowned woman and her husband, The Eagle and the Beetle, The Eagle Wounded by an Arrow, The Elm and the Vine, The Embarrassment of Riches, The Fox and the Grapes, The Fox and the Lion, The Fox and the Mask, The Fox and the Sick Lion, The Frog and the Mouse, The Frogs Who Desired a King, The Gourd and the Palm-tree, The Hare in flight, The Hedgehog and the Snake, The Man who Runs after Fortune, The Monkey and the Cat, The Mouse and the Oyster, The North Wind and the Sun, The Oak and the Reed, The Old Man and his Sons, The Old Woman and the Wine-jar, The Pilgrim's Progress, The Quack Doctor, The Satyr and the Traveller, The Tortoise and the Hare, The Walnut Tree, Thomas Jenner (publisher), Walther Damery, Washing the Ethiopian White, William Marshall (illustrator), Winged lion, Woodcut, Xanthippe, Yorick, Zacharias Heyns, Zeus and the Tortoise

See also

- 16th century literature

- 17th century literature

- Devises héroïques

- Lady Drury's Closet

- Georgette de Montenay

- Hypnerotomachia Poliphili

- Full text of "Iconologia, or, Moral emblems"

- Emblemata Amatoria (1611) by P.C. Hooft

- Illustrated fiction

- La Morosophie (Macé Bonhomme, 1553) is a book by Guillaume de La Perrière

- Emblem books of the Low Countries