Modern art

From The Art and Popular Culture Encyclopedia

_by_Édouard_Manet.jpg)

|

["Goya] was the last of the great masters and the first of the moderns."--Promenades of an Impressionist (1910) by James Huneker “Romanticism and modern art are one and the same thing” --Charles Baudelaire, 1846 "We stand at the threshold of an altogether new art - an art with forms which mean or represent nothing, recall nothing, yet which can stimulate our souls as deeply as only the tones of music have been able to." --August Endell on abstract art The Beauty of Form and Decorative Art, 1897-98. "The history of modern painting, one of the greater glories of modern France, is briefly as follows: In the early part of the nineteenth century, a definite and determined reaction against the erotic pictures of Boucher, Fragonard, and Greuze was ushered in by Vien and apotheosized by David. Austere, prudish, insipid themes from Greek and Roman history became the fashion. The classical tradition of the méthode David was continued by Ingres, a superlative draughtsman, whose pencil sketches make him, in Huneker's phrase, the greatest master of pure line who ever lived." With the advent of Géricault and Delacroix, French art broke away from the stiff formal tradition, with its historical or literary subject-matter. Géricault was almost the only artist in the nineteenth century who dissected, and he dissected even the viscera. With Géricault and Delacroix came two of the fundamental postulates of modern painting, viz., unrestricted freedom in the choice of subjects and the feeling that color rather than line is its true means of expressing form, volume, depth, light, air, and motion. Emancipation from formal or literary subject-matter was largely due to the Spanish artist Goya, who boldly took his themes from the varied life about him, painting almost every conceivable subject, and, in his diabolical etchings, revived the intensely dark backgrounds of Rembrandt and Hals. From Goya stemmed Gustave Courbet, who was reviled all his life for his daring choice of unconventional subjects and who was one of the earliest of the great landscape painters of France. From the Spanish tendency came also the caricaturist Honore Daumier, whose gloomy backgrounds again suggest Rembrandt and Goya, and whose nude studies of bathing and wrestling scenes introduced a tendency of colossal importance in recent painting, namely, the rendering of mass in motion, of the sensations of tactile volume, contour, weight, and muscular exertion by the sheer and rugged blocking out of dark tones against the light. It is the physiological anatomy of Michelangelo rendered in a new medium. Another product of the Goya tradition was Edouard Manet, who exhausted all the possibilities of unconventional subject-matter ("After Manet, there was nothing new to paint"), who eliminated nonessentials to the point of elliptical portraiture of the face, but who, with all his feeling for surfaces, never achieved form, depth, and volume in three dimensions. With Manet, came the great landscape painters of the Barbizon School and, inspired by the English Turner, the Impressionists, better termed the Luminists, who sought to represent sunlight, heat, wind, and flowing water by means of color alone. The Impressionist movement culminated in Paul Cézanne, who strove to represent form, subjective solidity, and movement itself by the juxtaposition of planes of color. As Berenson says, Cézanne gave tactile values even to the sky. These new devices were, most of them, utilized in triumphant synthesis in the last paintings of the aged Paul Renoir, defined by Wright as "among the greatest paintings of all time." The summit having been attained, decadence at once set in. Cézanne and Whistler had been influenced by the Japanese. Matisse reverted to the flat two-dimensional art of Persia. Out of African negro sculpture and its angularities came Picasso and the Cubists, who discarded color in favor of block representation in two tones and volume in favor of multilateral vision, or the simultaneous presentation of many aspects of the same object ("Nude Descending a Staircase"). The Futurists, meanwhile, aspired to empathy" or the identification of the spectator with a series of successive or simultaneous actions supposed to be represented in the picture ("Dynamism of an Auto"). This was the "cosmic tarantella," the chaotic Walt Whitman view of nature, which Berenson derides as the logical opposite of true art, the essence of which, from the time of the Greeks, has been selection. Finally, in the work of the Synchromists, all subject-matter in the shape of recognizable objects was eliminated in favor of experiments in juxtaposition of primary colors, and the sterilizing process was complete. Viewed historically. Cubism and Synchromism are technical experiments toward the purification of painting as the art of conveying sensations of form, volume, and move- ment by means of color alone.* In sculpture, Falguidre followed the traditions of Canova and Houdon; Rodin revived the muscular anatomy of Michelangelo. The effect of the purifying process upon anatomical representation in painting and sculpture was characteristic. To a surprising science of anatomy, acquired by dissecting, the great Florentine artists added their own intuitions about the dynamics of ' Berenson J The Central Italian Painters of the Renaissance, New York, 1897, p. loi. This argument has been derived, in the main, from Willard Huntington Wright's Modern Painting (New York, 1915), which does for modern French painters what Berenson 's volumes do for the Italian painters of the Renaissance. |

|

Related e |

|

Featured: |

Modern art is a general term used for most of the artistic production from the 1860s until approximately the 1970s. (Recent art production is more often called Contemporary art or Postmodern art). Modern art refers to the then new approach to art which placed emphasis on representing emotions, concepts and various abstractions. Artists experimented with new ways of seeing, with fresh ideas about the nature, materials and functions of art, often moving further toward abstraction.

While there is much disagreement on just what constitutes modern art, everyone agrees that it started in 19th century Paris. Walter Benjamin called Paris "the capital of the 19th century". Paris yielded this position of art capital of the world in the 1940s, when the center of artistic activity gravitated towards New York.

While in common parlance modern art is usually used to denote art of the early 20th century (Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism and Futurism), one will have to distinguish between modern art and modernist art. By this token modern art is Delacroix's Romanticism, Courbet's Realism, and Manet's Naturalism. Charles Baudelaire considered Delacroix as the originator of modern art, calling him in his review of the Paris Salon of 1846 "leader of the modern school."

Both modern and modernist art were firmly rooted in 19th century France and both are manifestations of the cult of ugliness that opposed the Academic ideal of the beautiful.

Contents |

History of Modern art

Roots in the 19th century

Although modern sculpture and architecture are reckoned to have emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, the beginnings of modern painting can be located earlier. The date perhaps most commonly identified as marking the birth of modern art is 1863, the year that Édouard Manet exhibited his painting Le déjeuner sur l'herbe in the Salon des Refusés in Paris. Earlier dates have also been proposed, among them 1855 (the year Gustave Courbet exhibited The Artist's Studio) and 1784 (the year Jacques-Louis David completed his painting The Oath of the Horatii). In the words of art historian H. Harvard Arnason: "Each of these dates has significance for the development of modern art, but none categorically marks a completely new beginning .... A gradual metamorphosis took place in the course of a hundred years."

The strands of thought that eventually led to modern art can be traced back to the Enlightenment, and even to the seventeenth century. The important modern art critic Clement Greenberg, for instance, called Immanuel Kant "the first real Modernist" but also drew a distinction: "The Enlightenment criticized from the outside ... . Modernism criticizes from the inside." The French Revolution of 1789 uprooted assumptions and institutions that had for centuries been accepted with little question and accustomed the public to vigorous political and social debate. This gave rise to what art historian Ernst Gombrich called a "self-consciousness that made people select the style of their building as one selects the pattern of a wallpaper."

The pioneers of modern art were Romantics, Realists and Impressionists. By the late 19th century, additional movements which were to be influential in modern art had begun to emerge: post-Impressionism as well as Symbolism.

Influences upon these movements were varied: from exposure to Eastern decorative arts, particularly Japanese printmaking, to the colouristic innovations of Turner and Delacroix, to a search for more realism in the depiction of common life, as found in the work of painters such as Jean-François Millet. The advocates of realism stood against the idealism of the tradition-bound academic art -- as testified by the print "Combat des écoles. - L'Idéalisme et le Réalisme" -- that enjoyed public and official favor. The most successful painters of the day worked either through commissions or through large public exhibitions of their own work. There were official, government-sponsored painters' unions, while governments regularly held public exhibitions of new fine and decorative arts.

The Impressionists argued that people do not see objects but only the light which they reflect, and therefore painters should paint in natural light (en plein air) rather than in studios and should capture the effects of light in their work. Impressionist artists formed a group, Société Anonyme Coopérative des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs ("Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers") which, despite internal tensions, mounted a series of independent exhibitions. The style was adopted by artists in different nations, in preference to a "national" style. These factors established the view that it was a "movement". These traits—establishment of a working method integral to the art, establishment of a movement or visible active core of support, and international adoption—would be repeated by artistic movements in the Modern period in art.

Early 20th Century

Among the movements which flowered in the first decade of the 20th century were Fauvism, Cubism, Expressionism and Futurism.

World War I brought an end to this phase, but indicated the beginning of a number of anti-art movements, such as Dada and the work of Marcel Duchamp, and of Surrealism. Also, artist groups like de Stijl and Bauhaus were seminal in the development of new ideas about the interrelation of the arts, architecture, design and art education.

Modern art was introduced to the United States with the Armory Show in 1913, and through European artists who moved to the U.S. during World War I.

After World War II

It was only after World War II, though, that the U.S. became the focal point of new artistic movements. The 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of Abstract Expressionism, Color field painting, Pop art, Op art, Hard-edge painting, Minimal art, Lyrical Abstraction, Postminimalism and various other movements; in the late 1960s and the 1970s, Land art, Performance art, Conceptual art and Photorealism among other movements emerged.

Around that period, a number of artists and architects started rejecting the idea of "the modern" and created typically Postmodern works.

Starting from the post-World War II period, fewer artists used painting as their primary medium; instead, larger installations and performances became widespread. Since the 1970s, new media art has become a category in itself, with a growing number of artists experimenting with technological means such as video art.

Art movements and artist groups

(Roughly chronological with representative artists listed.)

Roots of modern art

19th century

- Romanticism the Romantic movement - Francisco de Goya, J. M. W. Turner, Eugène Delacroix

- Realism - Gustave Courbet, Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet

- Impressionism - Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley

- Post-impressionism - Georges Seurat, Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri Rousseau

- Symbolism - Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, James Ensor

- Les Nabis - Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton

- pre-Modernist Sculptors - Aristide Maillol, Auguste Rodin

Early 20th century (before World War I)

- Art Nouveau & variants - Jugendstil, Modern Style, Modernisme - Aubrey Beardsley, Alphonse Mucha, Gustav Klimt,

- Art Nouveau Architecture & Design - Antoni Gaudí, Otto Wagner, Wiener Werkstätte, Josef Hoffmann, Adolf Loos, Koloman Moser

- Cubism - Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso

- Fauvism - André Derain, Henri Matisse, Maurice de Vlaminck

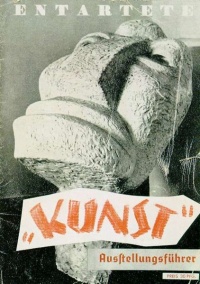

- Expressionism - Egon Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka, Edvard Munch, Emil Nolde

- Futurism - Giacomo Balla, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà

- Die Brücke - Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

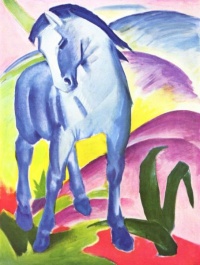

- Der Blaue Reiter - Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc

- Orphism - Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, Jacques Villon

- Photography - Pictorialism, Straight photography

- Post-Impressionism - Emily Carr

- Pre-Surrealism - Giorgio de Chirico, Marc Chagall

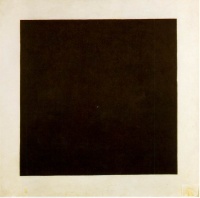

- Russian avant-garde - Kasimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov

- Sculpture - Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Constantin Brâncuşi

- Synchromism - Stanton MacDonald-Wright, Morgan Russell

- Vorticism - Wyndham Lewis

World War I to World War II

- Dada - Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Francis Picabia, Kurt Schwitters

- Synthetic Cubism - Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, Pablo Picasso

- Pittura Metafisica - Giorgio de Chirico, Carlo Carrà, Giorgio Morandi

- De Stijl - Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian

- Expressionism - Egon Schiele, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine

- New Objectivity - Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz

- Figurative painting - Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard

- American Modernism - Stuart Davis, Arthur G. Dove, Marsden Hartley, Georgia O'Keeffe

- Constructivism - Naum Gabo, Gustav Klutsis, László Moholy-Nagy, El Lissitzky, Kasimir Malevich, Vadim Meller, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin

- Surrealism - Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, René Magritte, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marc Chagall

- Bauhaus - Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Josef Albers

- Sculpture - Alexander Calder, Alberto Giacometti, Gaston Lachaise, Henry Moore, Pablo Picasso, Julio Gonzalez

- Scottish Colourists - Francis Cadell, Samuel Peploe, Leslie Hunter, John Duncan Fergusson

- Suprematism - Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandra Ekster, Olga Rozanova, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Ivan Kliun, Lyubov Popova, Nikolai Suetin, Nina Genke-Meller, Ivan Puni, Ksenia Boguslavskaya

- Precisionism - Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth

After World War II

- Figuratifs - Bernard Buffet, Jean Carzou, Maurice Boitel, Daniel du Janerand, Claude-Max Lochu

- Sculpture - Henry Moore, David Smith, Tony Smith, Alexander Calder, Isamu Noguchi, Alberto Giacometti, Sir Anthony Caro, Jean Dubuffet, Isaac Witkin, René Iché, Marino Marini, Louise Nevelson

- Abstract expressionism - Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell

- American Abstract Artists - Ilya Bolotowsky, Ibram Lassaw, Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers, Burgoyne Diller

- Art Brut - Adolf Wölfli, August Natterer, Ferdinand Cheval, Madge Gill, Paul Salvator Goldengreen

- Arte Povera - Jannis Kounellis, Luciano Fabro, Mario Merz, Piero Manzoni, Alighiero Boetti

- Color field painting - Barnett Newman, Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Sam Francis, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Helen Frankenthaler

- Tachisme - Jean Dubuffet, Pierre Soulages, Hans Hartung, Ludwig Merwart

- COBRA - Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel, Asger Jorn

- De-collage - Wolf Vostell, Mimmo Rotella

- Neo-Dada - Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, John Chamberlain, Joseph Beuys, Lee Bontecou, Edward Kienholz

- Fluxus - George Maciunas, Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell, Nam June Paik, Daniel Spoerri, Dieter Roth, Carolee Schneeman, Alison Knowles, Charlotte Moorman, Dick Higgins

- Happening - Allan Kaprow, Joseph Beuys, Wolf Vostell, Claes Oldenburg, Jim Dine, Red Grooms, Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Robert Whitman, Yoko Ono

- Dau-al-Set - founded in Barcelona by poet/artist Joan Brossa, - Antoni Tàpies

- Grupo El Paso - founded in Madrid by artists Antonio Saura, Pablo Serrano

- Geometric abstraction - Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, Nadir Afonso, Manlio Rho, Mario Radice, Mino Argento

- Hard-edge painting - John McLaughlin, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Al Held, Ronald Davis

- Kinetic art - George Rickey, Getulio Alviani

- Land art - Christo, Richard Long, Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer

- Les Automatistes - Claude Gauvreau, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Gauvreau, Fernand Leduc, Jean-Paul Mousseau, Marcelle Ferron

- Minimal art - Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd, Dan Flavin, Richard Serra, Agnes Martin

- Postminimalism - Eva Hesse, Bruce Nauman, Lynda Benglis

- Lyrical abstraction - Ronnie Landfield, Sam Gilliam, Larry Zox, Dan Christensen, Natvar Bhavsar, Larry Poons

- Neo-figurative art - Fernando Botero, Antonio Berni

- Neo-expressionism - Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Jörg Immendorff, Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Transavanguardia - Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino, Sandro Chia, Enzo Cucchi

- Figuration libre - Hervé Di Rosa, François Boisrond, Robert Combas

- New realism - Yves Klein, Pierre Restany, Arman

- Op art - Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, Richard Anuszkiewicz

- Outsider art - Howard Finster, Grandma Moses, Bob Justin

- Photorealism - Audrey Flack, Chuck Close, Duane Hanson, Richard Estes, Malcolm Morley

- Pop art - Richard Hamilton, Robert Indiana, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, David Hockney

- Postwar European figurative painting - Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Frank Auerbach, Gerhard Richter

- New European Painting - Luc Tuymans, Marlene Dumas, Neo Rauch, Bracha Ettinger, Michaël Borremans, Chris Ofili

- Shaped canvas - Frank Stella, Kenneth Noland, Ron Davis, Robert Mangold.

- Soviet art - Alexander Deineka, Alexander Gerasimov, Ilya Kabakov, Komar & Melamid, Alexandr Zhdanov, Leonid Sokov

- Spatialism - Lucio Fontana

- Video Art - Nam June Paik, Wolf Vostell, Joseph Beuys, Bill Viola

- Visionary art - Ernst Fuchs, Paul Laffoley, Michael Bowen

See also

- Possible originary dates for the birth of modern art

- Modernism

- Art movements and artist groups

- List of modern artists

- Museums of modern art

- Contemporary art

- Postmodern art

- Art periods

- Modern architecture

- Art manifesto

- History of painting

- Western painting

_by_Oskar_Schlemmer.jpg)